Commentary: Donald Trump wants to be the emperor of Latin America

Published in Op Eds

Last week, Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro was on stage in front of his supporters, waving his hands and dancing, seemingly oblivious to the danger that awaited him. Monday, that same man was a criminal defendant incarcerated at the Metropolitan Detention Center in New York’s Brooklyn borough, having just been arraigned on drug trafficking, narcoterrorism and weapons charges.

Maduro’s fall from grace happened in the middle of the night while he was tucked in bed. After coordinated airstrikes against Venezuelan airfields to knock out the country’s air defense network, low-flying helicopters carrying U.S. special operations forces swooped down on Maduro’s hideout, killed his Cuban security team and whisked him and his wife, Cilia Flores, away to the USS Iwo Jima offshore. Venezuelans awoke the next morning to news that the tall, burly man who had ruled the country for nearly 13 years and through fraudulent elections was forcefully extradited by the Americans back to the United States to stand trial. The whole operation was as smooth as silk.

Much of the coverage to date has focused on the nuts and bolts of how the U.S. snatch-and-grab mission was conducted. But there’s a bigger theme to highlight: What happened in Venezuela over the weekend is the most dramatic illustration of the so-called Trump corollary for the Western Hemisphere. And it can be best summed up simply: As a matter of policy, the United States aspires to sole dominance of the region.

To students of history, this ambition isn’t new. Similar to other great powers, the United States has long looked at its near-abroad at its exclusive domain, where the influence of geopolitical competitors must be constrained to the maximum extent possible. The list of U.S. covert actions and outright interventions in Latin America is about as long as a 5-year-old’s wish list for Santa: the U.S. invasions of Mexico in 1846 and 1914; the U.S. invasion of Cuba in 1898; the U.S. occupation of Haiti between 1915 and 1934; the 1954 coup against Guatemala’s leftist government; and the U.S. invasion of Panama in 1989, to name just a few. Washington under both Republican and Democratic presidents has thrown America’s weight around to mold the region to its liking.

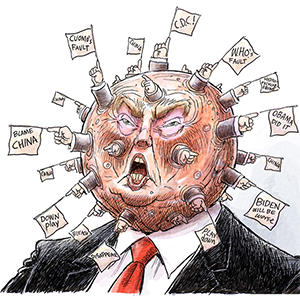

Trump has carried on with that tradition, albeit in a more heavy-handed way. In the past, U.S. presidents largely justified interventions, coups and various other pressure tactics against adversarial governments at an attempt to spread democracy, contain the threat of other great powers or make Latin America writ-large a more stable place. Trump, however, is unapologetically brandishing U.S. power to, in effect, create an entire hemisphere full of supplicants willing to do America’s bidding. Some Democratic lawmakers have called it a form of 21st century imperialism. While the “i-word” is a dirty one in the U.S. vocabulary and conjures up days of colonies, empires and the strong pummeling the weak into submission, it’s not totally out of left field. And if we’re being honest, Trump probably wouldn’t have too much of a problem with the characterization.

The Trump administration has argued from the get-go that Maduro is a master manipulator, a fraud, a gangster and one of the world’s chief narcos who shipped copious amounts of cocaine into the United States for the profits. The only option, U.S. officials have said, is removing him from office and prosecuting him in a U.S. court. And such a move, while brazen, isn’t unprecedented — 37 years ago, President George H.W. Bush did the same exact thing when he invaded Panama, captured its dictator Manuel Noriega and flew him back to the United States, where he was convicted and sentenced to 40 years in prison for drug trafficking.

The difference, however, is that unlike his predecessors, Trump is more brash about leveraging all the tools of U.S. power and doesn’t even bother to make a coherent case about why he’s doing it. He also isn’t using the typical talking points and justifications prior U.S. presidents have used. In some ways, this is refreshing; after all, does anyone truly believe that overthrowing a democratically elected government in Guatemala and supporting military coups in Chile and Brazil during the Cold War were about saving democracy?

On the other hand, Trump’s actions aren’t without costs. For tens of millions of people already suspicious of U.S. motives in Latin America and aware of its history there, the capture of Maduro reaffirms their belief that what Washington cares about first and foremost is enhancing its control over the region’s politics and crushing anyone in its path. The fact that Maduro was a reviled figure in much of the Western Hemisphere and deserving of his fate doesn’t mean that a significant chunk of the region, particularly Latin American states with leftist or center-left leaders, don’t take issue with the way the United States violated another country’s sovereignty to arrest its de facto head of state. One of those states is Brazil, where President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva issued a statement pillaring Washington for crossing “an unacceptable red line” and calling on the United Nations to respond strongly. Another example is Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, a leader who has gotten along with Trump on both a personal and professional level but nevertheless condemned the attack.

Despite those concerns, Venezuela could very well be the beginning of the story, not the end. The successful stealth operation against Maduro has emboldened Trump to even newer heights. He’s openly talking about military action against cocaine labs in Colombia, annexing Greenland and returning to his consistent flirtation with bombing cartels in Mexico.

What is unmistakably clear is that the United States now expects a degree of subjugation from the Western Hemisphere. Or else.

____

Daniel DePetris is a fellow at Defense Priorities and a foreign affairs columnist for the Chicago Tribune.

___

©2026 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments