Commentary: America's 'Common Sense' revolution

Published in Op Eds

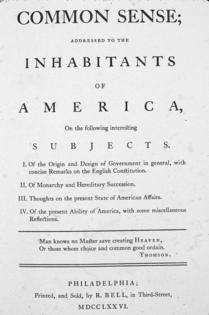

While Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence turned the smoldering embers of rebellion into the glorious fireworks of independence and revolution, it was a short pamphlet published six months earlier, in January 1776, that ignited the colonies’ revolutionary zeal and crowded out any notion of rapprochement with Britain.

Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense,” a mere 47 pages long, “swept through the colonies like a firestorm, destroying any final vestige of loyalty to the British crown,” according to historian Joseph Ellis, a prominent Jefferson biographer.

“Common Sense,” as the title implies, is full of practical arguments. The colonies need to declare independence, Paine wrote, because so long as their goal was seen as reconciliation, foreign governments would consider the Americans as rebels and the conflict an internal affair. Declaring independence, Paine argued, would turn the rebellion into a war between sovereign states and open the door for a negotiated peace.

Moreover, without a commitment to independence, the Americans would not be able to secure assistance from France or Spain. Why, Paine asked, would Britain’s rivals choose to support the colonists if their stated goal was to reunite with the mother country?

Finally, to assuage any fears among potential allies that Americans might seek to promote rebellion in their countries, Paine thought it important for the colonists to lay out their grievances and their efforts to see them addressed. Separation needed to be seen as a last resort. As the Declaration would later state, the colonists did not seek independence for “light and transient causes,” but rather as a last resort to restore their rights. France and Spain, therefore, need not fear any contagion of revolution reaching their shores from the Americas.

The pamphlet went viral. There were 2.5 million people in the 13 colonies in 1776. More than 500,000 copies were distributed, or one copy for every five Americans. As a percentage, it doesn’t quite match illusionist Zach King’s “Magic Broomstick” (2 billion views, or 25% of the world population), it dwarfs the popularity of “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone” (a mere 120 million copies worldwide).

John Adams, who would later become America’s first vice president, and after that, its second president, wrote, “Without the pen of Paine, the sword of Washington would have been wielded in vain.” George Washington ordered it read to his troops and commented that it “is working a powerful change there in the minds of men.”

Paine’s arguments for independence helped change history, but he also included a long section on the ills of monarchy, drawing on the Jewish Bible’s recounting of the Jewish people’s demand for a King (1 Samuel 8:5) and the prophet Samuel’s warning of the abuses that would result.

Paine called on the colonists to declare that in America, “THE LAW IS KING. For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be King.”

This points to a core American principle: that in America, we are governed by the rule of law, not the diktats or whims of individuals.

While a select few American families have succeeded in producing multiple presidents (the Adamses, Bushes, etc.), family dynasties have yet to succeed here.

While “Common Sense” made a compelling case for independence, Paine began his pamphlet by outlining a radical — and controversial — theory of government.

On his account, the role of government was extremely limited. “Society is produced by our wants,” he wrote, “and government by our wickedness.” Society is a “patron,” while government is a “punisher.” “Government, even in its best state, is but a necessary evil.”

Paine’s radical critique of government frightened some, including Adams, who later wrote, “I dreaded the Effect so popular a pamphlet might have among the People, and determined to do all in my Power to counteract the Effect of it.”

Still, Paine’s recognition that Americans’ lives are primarily mediated through voluntary associations in “society,” rather than the coercive power of government, would come to define one of the most admired aspects of American democracy throughout its 250-year history.

____

ABOUT THE WRITER

Frederic J. Fransen is the president of Ameritas College Huntington (W.Va.) and CEO of Certell Inc. He wrote this for InsideSources.com.

_____

©2026 Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments