Good government fix or a demolition derby? Historic preservation bill is provoking debate in Philadelphia

Published in Business News

Historic preservation advocates are sounding the alarm about legislation from Councilmember Mark Squilla, which they argue would weaken existing protections in Philadelphia.

The bill, introduced Nov. 20, would institute changes to the city’s Historical Commission, which regulates properties on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places and ensures that they cannot be demolished or their exteriors substantially altered.

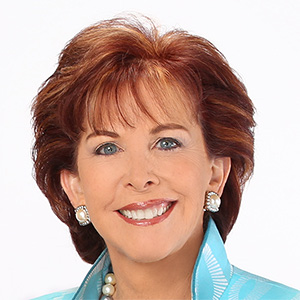

“This is the first time the [preservation] ordinance has been proposed for amendment in decades,” said Paul Steinke, executive director of the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia. “This is a developer-driven proposal that does not reflect any of the priorities of the preservation community.”

Proponents of the bill argue that it is simply meant to give more notice and power to property owners before their buildings are considered by the Historical Commission.

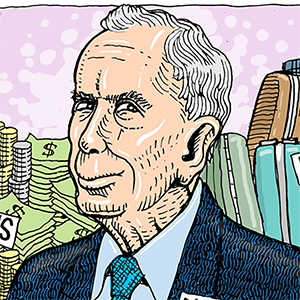

“The bill does nothing to decrease the power of the Historical Commission to protect important historic resources,” said Matthew McClure, who served as co-chair of the regulatory committee of Mayor Jim Kenney’s preservation task force.

“It is a modest good government piece of legislation,” said McClure, a prominent zoning attorney with Ballard Spahr. He emphasized that he was not speaking on behalf of a client.

The bill was introduced too late in this year’s Council session to receive a hearing. Squilla says it will be considered next year.

Currently, the interest group most supportive of the bill is the development industry. But even some preservation opponents are displeased with Squilla’s effort, arguing that it does too little for homeowners.

“Everybody’s talking, and I think they all agree to move forward with continued conversations to maybe tweak the language a little bit so everybody feels comfortable with it,” Squilla said.

At least one more stakeholder meeting will be held in December.

Tensions over preservation

Squilla’s proposal comes in the midst of heightened debate around preservation in Philadelphia, where the majority of buildings were constructed before 1960.

Over the last decade, the number of historically protected properties doubled, although well below 5% of the city’s buildings are covered. Preservationists oppose what they see as a demolition-first approach to development in the United States’ only World Heritage City.

Recently large new historic districts have been created to cover neighborhoods like Powelton Village, parts of Spruce Hill, and 1,441 properties in Washington Square West.

These have provoked backlash among some homeowner groups and pro-development advocacy organizations, which see these regulations as increasing housing costs.

Some property owners have grievances against the way the local nomination process works.

In Philadelphia, citizens are empowered to nominate buildings to the local register — giving buildings protection from demolition or exterior changes — without input from the property owner until the Historical Commission considers the case.

This practice persistently causes controversy, especially because there are few local incentives for homeowners whose properties get protected.

In some localities, preservation protections are promulgated exclusively by planners. In others, owner consent is required.

“The current historic nomination process is most often dictated by nongovernmental actors who operate without notice to property owners,” McClure said. “The administration’s bill is aimed at increasing transparency and basic fairness during the nomination process.”

Mayor Cherelle L. Parker’s administration did not respond to a request for comment.

What’s in the bill

Squilla’s bill is thick with new provisions to the local historic ordinance. A key aspect of the legislation gives property owners at least 30 days before a pending nomination of their building is considered by the commission and protections kick in.

While homeowners probably would not have time to radically alter the exterior of their house — and presumably wouldn’t demolish it — preservationists fear that developers will use the extra time to begin razing historic buildings.

“No one likes the notice provision the way it’s written; that’s freaking people out,” Steinke said. “We made clear why we think that’s a problem, and we were heard. Of course, the development community would love it to be the way it’s currently expressed in the bill.”

The delayed provision particularly worries preservationists in combination with a proposed requirement that the commission approve permits — including demolition or exterior design work — if “material commitments” were made to plans before the attempt to protect the historic building.

Other provisions include language to make it more difficult to protect land because it may house archaeological remains. It also limits the ability to consider a property for protection due to its relation to a landscape architect (as opposed to, say, a building designer).

Why some preservation critics dislike the bill

One critic of Squilla’s bill is a new group of residents angry at the costs of preservation protections to homeowners following the creation of the Washington Square West historic district.

Despite their animus toward existing preservation rules in the city, groups like 5th Square and Philadelphians for Rational Preservation called the legislation a sop to those who least need help.

“While this bill is a boon to developers, it doesn’t help ordinary Philadelphians,” said Jonathan Hessney of Philadelphians for Rational Preservation.

He argues that Squilla isn’t curbing historic districts that burden homeowners, “while at the same time risks allowing genuinely historic properties to be destroyed in the new 30-day race to demolish or deface it creates.”

A possible reform that some critics of the bill would like to see are flexible, tiered historic districts, where only a select group of buildings would be fully regulated. Demolition protections would still exist for many buildings, but most would not be subjected to oversight for changes like replacing a door or window.

“That was discussed as something that the preservation community would like to see that was mentioned in the original draft and then stripped out,” Steinke said.

Squilla said the pushback surprised him, given that negotiations have been held since June. He’s confident a compromise can be reached.

Beyond the Preservation Alliance — the advocacy group with the most funding and pull in City Hall — the bill has caused alarm among historic activists.

“It was a blindside to the progress that many stakeholders in the preservation community felt they were reaching with him,” said Arielle Harris, an advocate. “Squilla understands the preservation climate in the city — given that he was on the preservation task force — so this is out of left field.”

©2025 The Philadelphia Inquirer, LLC. Visit at inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments