Philadelphia Whole Foods workers filed for a union a year ago. Here's what's holding up their contract

Published in Business News

Nearly a year after Philadelphia Whole Foods workers voted to form a union, becoming the first group in the grocery chain to do so, their union’s ability to move forward and negotiate a contract is locked in a procedural standstill.

The Monday before Thanksgiving, workers and supporters gathered outside the Pennsylvania Avenue store, holding signs that read “Amazon-Whole Foods: Treat workers with respect & dignity!” Nearby, an inflatable “fat cat,” used by labor organizers and often denoting a person who uses wealth to exert power, stood tall outside the Whole Foods store.

Edward Dupree, who has been employed at Whole Foods for over nine years and works in the produce department at the Philadelphia store, told the crowd that in the 1970s, unionized grocery employees could maintain a middle-class family, but today workers are facing rising housing and healthcare costs as well as uncertainty in the economy.

“There’s been a concerted effort by billionaire business class — folks like (Amazon and Whole Foods owner) Jeff Bezos — to crush working class power by fighting unions like this,” said Dupree. “For 50 years, we’ve seen the worsening of living standards in tandem with the drop of unionization rates. It’s been long due for us to stand up for one another and fight back for a better future.”

Workers at the Philadelphia grocery store filed a petition to unionize with the National Labor Relations Board in November 2024 and made history in January as the first company store to successfully vote to unionize.

Employees want the company to begin negotiating a first contract, but for now, the case is at a standstill. Whole Foods has challenged the union election, and resolution of the issue lies with the National Labor Relations Board, which for months has been without the required quorum to make a decision since President Donald Trump fired a board member.

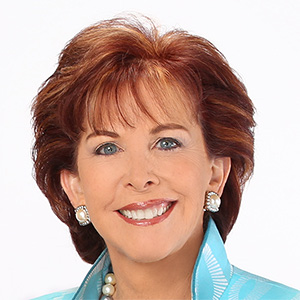

“We want Whole Foods to do what they’re obligated to do. What’s right to do is sit down and bargain a contract,” said Wendell Young IV, president of UFCW Local 1776, the union that Whole Foods workers elected to join. “We understand there’s a give and take in that process, but that’s from both sides. They’re refusing to even sit down and begin those discussions for a contract.”

Why is the Whole Foods case at a standstill?

Whole Foods raised multiple objections to the worker union election earlier this year including alleging that the union promised employees would get a 30% raise if they voted for a union.

In May, the National Labor Relations Board’s regional director dismissed the challenge by Whole Foods, but the company asked for that decision to be reviewed. The union, for its part, has tried to block that review, but the board can’t make a decision either way without the required quorum.

“As previously stated, we strongly disagree with the regional director’s conclusion, and as demonstrated throughout the hearing earlier this year, including with firsthand testimony from various witnesses, the UFCW 1776 illegally interfered with our team members’ right to a fair vote at our Philly Center City store,” a spokesperson for Whole Foods Market said via email.

A union spokesperson said via email that they must wait until the board again has at least three members to review the case and added, “We expect that we will be successful at that time.”

Young, the president of the union local, has said in the meantime that the company is hiding behind the situation at the NLRB “to refuse to bargain.”

In the 1960s and into the 1970s, when it was not uncommon in the U.S. to see grocery workers strike or threaten to, Republicans and Democrats in office understood that unions were a permanent part of the economy, said Francis Ryan, a labor history professor at Rutgers University who has been a member of UFCW local 1776. The NLRB “provided some balance between the company and the union,” acknowledging that both parties “had an important role to play in our society,” he said.

“What we have in more recent years is a much more polarized political context, where the National Labor Relations Board is sometimes stocked with people who are aggressively anti-union,” said Ryan.

The Trump administration firing an official at the NLRB and not replacing them “is a deliberate attempt to make the process of collective bargaining and also organizing much more difficult,” said Ryan, adding that this is playing out in the case of Whole Foods.

UFCW Local 1776, which Whole Foods workers in Philadelphia elected to join, represents thousands of workers across Pennsylvania and neighboring states in drugstores and food processing facilities, among other areas of work. The union represents grocery employees at ShopRite, Acme and the Fresh Grocer.

Under the ownership of Amazon, the quality of work life atWhole Foods has deteriorated, said Young, adding that the company has unrealistic expectations and doesn’t compensate workers fairly in terms of wages, healthcare, retirement security.

“These people have no say in any of that — and that’s what led them to organize,” he said.

Whole Foods has said employee benefits include 20% off in-store items, as well as a 401K plan that offers a company match. The company also says it evaluates wages to ensure it is offering a competitive rate.

The number of unionized workers at grocery stores grew in the 1950s and 1960s in large part because areas of the U.S. were becoming more suburban and adding new grocery stores in the process, according to Ryan.

“You had thousands of workers in these new supermarkets that were unionized, and they made the retail clerks union one of the largest unions in the United States by the time you get to the 1970s — and Philadelphia was one of the real centers of supermarket unionization.”

It wasn’t unusual in the 1960s and 1970s for someone to make a living as a supermarket worker, although it was not uncommon for workers to have more than one job, said Ryan. In some cases, workers would stay at a grocery store for decades, he says, where they made decent wages and had a stable job indoors, adding that between 1965 and 1975 the wages of retail workers in Philadelphia nearly doubled.

Since then, it’s become much harder to make a living overall in the service industry, says Ryan.

But having unionized grocery stores amid other nonunion stores today can help shape the economy of the industry, says Ryan. A business that wants to maintain a nonunionized workforce might try to pay their workers the same starting rate that union workers make in wages, for example.

Unionized grocery stores “have a hidden planet kind of role: They have this gravitational pull on the industry that actually raises conditions for everyone,” Ryan said.

While the Whole Foods store in Philadelphia is the first of the company’s locations to vote to form a union, others seem to be following.

“We now have active organizing going on, not only in other Whole Food stores in the area and around the country, but other grocery stores,” said Young.

©2025 The Philadelphia Inquirer, LLC. Visit at inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments