A Seattle shipyard charts major growth even as US shipbuilding struggles

Published in Business News

Sometime early next year, the Snow & Co. boatyard in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood will roll out its 180th boat.

It’s a major milestone for a family-owned company that only started building boats in 2012 — and an exception in an industry better known for closures and consolidation.

Part of that success is down to owner Brett Snow’s willingness to take chances.

On a recent morning in Snow’s capacious shop just off the Lake Washington Ship Canal, workers were assembling a 41-foot workboat for the U.S. Navy.

It's one of around two dozen Snow is building on a multimillion-dollar contract the company won, audaciously, in 2017, when the industry was cooling and Snow was just a 20-person outfit building fishing boats.

Bidding for the Navy job was ambitious for us," admits Snow, 59, who started out as a one-man boat repair shop in Ballard in the 1990s. "It definitely put us on a different trajectory."

Today, Snow has almost 100 employees designing and building everything from research vessels and dry-docks to one of the world’s first all-electric tugs.

But so much growth has meant taking other chances.

As with many manufacturing companies, Seattle-area boatbuilders face serious headwinds. Materials are more expensive. Competition from cheaper out-of-state yards is heating up. Above all, skilled workers are increasingly hard to find.

Snow has pushed ahead in part by expanding hiring beyond the traditional maritime labor pool to recruit immigrant, refugees, former prisoners and others.

On the shop floor, a master welder from Ukraine was mentoring a prison work-release program participant on part of the electric tug.

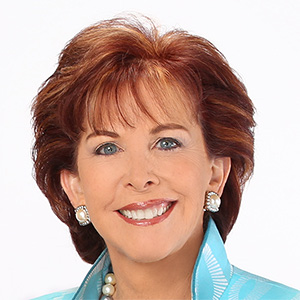

But it's slow going. Snow reckons the yard has enough orders that it could double its workforce. Instead, "we've had to turn work away because we didn't have enough hands,” says Tuuli Snow, Brett's daughter and talent acquisition manager.

‘Just not getting built’

Creative hiring is just one of the workarounds that have become essential in a struggling industry.

When Brett, a native of Sebastopol, Calif., arrived in Seattle in 1994, Washington had nearly 370 shipbuilding businesses making everything from tugs and seiners to sailboats and dinghies, state records show.

Most were in Puget Sound, long a shipyard hub for Navy boats and the Alaskan fishing fleet.

The Ship Canal and Lake Union in particular, protected from tides and corrosive saltwater, offered “one of the best places to do boat repair in the world,” said Snow, who lived with his family aboard a converted fishing trawler he’d sailed from Denmark.

But since then, more than 150 of those yards have gone away, among them some of the most storied names in Seattle's maritime industry: Marco Marine, Vic Franck’s Boat Co., Jensen Motor Boat and Fishing Vessel Owners.

Snow & Co itself works in a space that once housed Kvichak Marine Industries, a renowned maker of high-speed aluminum workboats, which closed in 2019 after being acquired by Vigor Industrial, the Portland-based giant that had also gobbled up Seattle’s Todd Shipyards in 2010.

Total industry revenues, which peaked in 2007 at $1.7 billion, have since fallen 41%, in inflation-adjusted terms, according to state revenue department data.

Some of that pullback is inevitable in a maturing industry, as family run boatyards run out of family and sell out to rivals or waterfront developers.

But many of Washington's former shipyards went unwillingly, dragged down by the economic tides that have eroded the U.S. shipbuilding industry.

One factor is weakening demand from some traditional vessel operators, like the commercial fishing operators who ordered Snow’s first aluminum vessels.

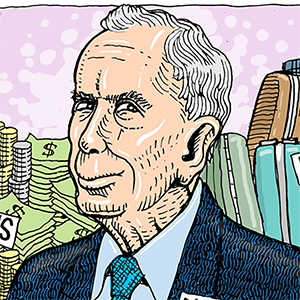

With growing uncertainty over future harvests, and with equipment costs rising much faster than fish prices, fleet owners are less willing to invest in new boats, said Joshua Berger, CEO of Maritime Blue, a Seattle nonprofit that promotes Seattle-based nonprofit that supports maritime innovation and markets.

Though the aging Seattle-based fishing fleet needs of dozens of new vessels, Berger said, “they're just not getting built.”

Where new vessels are in demand, some customers are increasingly tempted by out-of-state yards, which advertise lower costs, especially for labor.

That played out dramatically in July when the state awarded a contract for three new hybrid-electric ferries to a Florida-based shipyard instead of Whidbey Island's Nichols Bros. Boat Builders, whose bid was around $300 million more.

Under special “prevailing wage” rules for state contracts, building those ferries in-state would've meant paying workers nearly $59 an hour versus “sub-$30” in Florida, said Gavin Higgins, CEO of Nichols Bros.

But even for commercial boat projects without a prevailing wage requirement, shipyard wages in Washington average $10 to $12 an hour more than on the Gulf Coast, said Higgins.

Despite Washington boatyards' reputation for better quality work, Higgins said, some Pacific Northwest-based fishing operators have already “gone down to the Gulf and built their boats.”

It could be worse. Federal law requires that commercial vessels operating between U.S. ports be built in U.S. shipyards.

Absent that, Washington shipyards might lose even more business to Asia, where heavy government support and cheaper labor and materials result in shipbuilding costs far below those in the U.S., according to a 2023 Congressional Research Service report.

Already, China accounts for 55% of the world’s new vessel tonnage, up from 2.5% in 1990, according to CRS and United Nations data. America’s share, meanwhile, is down from 5% in the 1970s to less than a tenth of a percent.

That decline has spurred rare bipartisan action to revive U.S. shipbuilding. Proposed fixes range from heavy port fees on foreign-built ships to government support to update and expanding U.S. shipyards.

But any improvements could take years to materialize, by which time the worsening economics of boatbuilding could squeeze out more U.S. yards.

Already, the rising costs of new construction has pushed some yards to focus more on ship repair and maintenance rather than risk a big new construction project that winds up pulling a company under.

That’s a growing fear in the industry, said Brett Snow. “Somebody underbids a job, and it destroys them.”

Ships of the future

For Snow, avoiding that kind of outcome required a mix of strategies.

Early on, Snow obsessed on keeping costs down. He built an in-house design and engineering team who could work closely with his building crews and avoid the costly back-and-forth that can come with outside experts.

When demand for fishing vessels began cooling, Snow gambled that his cost-saving efficiencies were enough to let even a small company win a huge Navy workboat contract.

He adds, with a laugh, that Navy officials visiting the company after awarding the contract "saw our shop and were a little bit surprised how small we were."

The gamble paid off. The contract, which has already brought Snow around $40 million in revenue, let the company grow, with larger quarters, more employees and a more diverse and stable customer base.

Snow has also skirted the industry's historic contraction by betting heavily on the future.

The eight 78-foot electric tugs Snow is building could position the company for the much-anticipated electrification of parts of the maritime sector. “That's new technology in an old world,” said Snow.

Snow is one of several local yards pushing on next-generation technologies.

This year, Nichols Bros. completed an 180-foot unmanned “autonomous” vessel for the U.S. Defense Department, part of the global push toward crewless combat and commercial vessels.

The Defiant was "a pretty complicated boat to build and it takes a specialized [work] crew,” said CEO Higgins, of the vessel, which can be at sea for up to a year. But, he adds, "once you've built one, you have the knowledge to build [them in the] future, which puts you in a good place."

'We can teach them anything'

Fixing the industry’s labor shortage is more complicated.

Some of that is the same "silver tsunami" hitting other trades: many of the highly skilled workers who drove Seattle-area shipbuilding in its heyday are aging out.

But replacements are harder to find than they used to be. Fewer high schools offer the vocational classes that once fed the skilled trades.

Boat yards say the physically taxing nature of the work makes it a harder sell in a culture that worships white-collar knowledge work.

“We used to see people wanting to work overtime all the time, and that's not the case anymore,” said Russell Shrewsbury, vice president at Western Towboat, a Seattle-based tug and barge operator that builds its own vessels.

As with many skilled trades, salaries haven’t kept up with Seattle-area housing and other living costs.

Of the 40 employees working at Pacific Fishermen Shipyard in Seattle’s Ballard neighborhood, “maybe five people … actually live in the city,” said general manager Chris Johnson.

In the face of that shortfall, Snow & Company has a hiring strategy that is, literally, all over the map.

They've recruited from trade schools, such as the Seattle Maritime Academy and the Maritime High School in Des Moines. But they've also hired immigrants short on English but prodigiously skilled and partnered with Maritime Blue, which runs internships for women and minority students.

“One of the reasons we've tripled in size [since 2020] when other businesses are shutting down is because we hire people that others won’t,” said Tuuli Snow, a message she took to Congress during an October hearing on U.S. shipbuilding.

But Snow & Co also pushes a more traditional approach to finding new talent.

Brett Snow, who got interested in boats in high school, thinks that’s a prime age to get people interested in maritime industries. As part of that approach, Tuuli works closely with local high schools, such as Mount Si in Snoqualmie, that still boast strong shop and vocational programs.

“I personally love hiring kids right out of high school that … want to make stuff, use their hands,” Brett said.

These future boatbuilders may not be at the top of their class academically, Brett said. But if they’re motivated, a lot of the rest can be learned on the job. “If somebody is ambitious," he said, "we can teach them anything.”

©2025 The Seattle Times. Visit seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments