Abby McCloskey: What's worse than cherry-picked government data? None at all

Published in Op Eds

It was hard to know what to believe this year. In the old days, there were conspiracies about the moon landing. These days, it feels like there’s a conspiracy about everything — that the truth is up for grabs, alongside crusty government datasets.

Some people chose to verify what they heard with multiple sources, including legacy media. Others followed a podcaster or Substack writer who they thought had the corner on truth. And some just asked ChatGPT.

One of the rallying cries of our conspiratorial age is “do your own research.” But that’s not easy at the best of times. Some data require expertise and context to interpret. And this year, some reliable government datasets disappeared altogether. Others are incomplete thanks to 2025's Democrat-led government shutdown, the nation’s longest.

Yes, long-delayed numbers from that shutdown are now emerging — like high GDP growth and lower than expected inflation. But this new information is only adding to the confusion. The data is incomplete and partially being drawn from other sources, making comparisons difficult. It shows how damaging even temporary losses in government data can be.

It’s true that not all government statistics are perfect. Take the Census Bureau’s poverty math, as my friend and former AEI colleague Andrew Biggs has warned. Figures from 2023-2024 report that the Official Poverty Measure (OPM) for seniors increased from 9.7% to 9.9%. This is not so far off from the poverty rate of working-age adults, until you remember that seniors are getting monthly Social Security checks and free healthcare.

But Biggs points out that the Census OPM inexplicably doesn’t include ‘irregular income,’ such as withdrawals from 401(k)s. Accounting for this, the real poverty rate of seniors drops to 5.9%. The Census knows this and reports a new, supplementary way of calculating the poverty rate called “the NEWS,” but headlines of rising elderly poverty steal the show.

Or take maternal mortality rates. It’s long been said that the U.S. has the highest rate of maternal mortality in the developed world. But as I wrote in National Affairs, the U.S. also changed its measure of how to calculate maternal mortality. In 2003, the CDC began including a pregnancy check-box on death certificates even if the cause of death was not necessarily pregnancy-related.

This is widely recognized to have inflated the numbers. (In 2013, the pregnancy checkbox was used 187 times in deaths of people over age 85, according to economist Emily Oster.) Tighter definitions of maternal mortality rates strictly related to childbirth show U.S. rates to be elevated, but roughly on par with peer countries such as Canada and the UK, though maternal mortality rates for Black American mothers remain significantly higher.

What to make of these differences in government calculations? Some people might allege conspiracy — that someone inside the agency is massaging numbers. The books are cooked!

But the boring truth is that some things are harder to measure than they’d seem. And there are trade-offs in what and how we count. (For example, the "pregnancy box" was added because we were likely undercounting pregnancy-related deaths before.) Even in cases where we’ve come up with a more accurate way to measure something, there can be benefits to keeping consistent standards — they help us see trends over time.

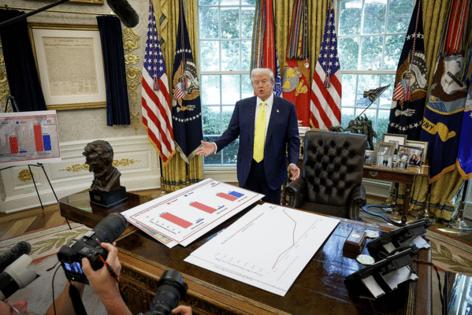

This year, the Trump Administration often stoked the former approach. President Trump fired Bureau of Labor Statistics Commissioner Erika McEntarfer after a lackluster jobs report in August. “We need accurate Jobs Numbers. I have directed my Team to fire this Biden Political Appointee, IMMEDIATELY,” President Donald Trump posted on Truth Social. He similarly accused Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell of slowballing rate cuts to make him look bad and misreading inflation data: “There is no Inflation, and every sign is pointing to a major Rate Cut.”

Other data simply disappeared on his watch, with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration no longer tracking billion-dollar weather disasters (which seem to be increasing) and delayed data rollouts from the Department of Education (which slows sliding student scores).

This mentality essentially means it’s all up for grabs. If you don’t like the data, you can fire the accountant, ignore the spreadsheet, delete the database. And you better believe that the next accountant will keep your happiness in mind when crunching the numbers.

But then how will we know what’s true? And if we lose our ability to tell, then what?

As Thomas Sowell wrote in Knowledge and Decisions: “The cavemen had the same natural resources at their disposal as we have today, and the difference between their standard of living and ours is a difference between the knowledge they could bring to bear on those resources and the knowledge used today.” This surely includes our embrace of and advancements in science: the relentless search for objective truth outside ourselves.

This isn’t to say that there aren’t improvements to be made in data collection. It is the responsibility of data collectors not to lock blindly into the old ways of doing things, but to constantly seek to make the data more holistic and transparent. Where there are alternative measures that can be used — for the poverty rate, or maternal mortality, or jobs numbers — they should publish them alongside the traditional metrics. The Congressional Budget Office, for example, releases multiple projection scenarios with each of its reports based on different assumptions that are spelled out.

And for us, it’s our responsibility to wrestle with numbers that challenge our assumptions, whether we’re journalists, policymakers or news consumers. But we must resist the belief that the entire federal data infrastructure is corrupt. While I don’t doubt that there are bad actors now and again in government, or that incentives within bureaucracies can become bloated and misguided, we should be slow to throw out data systems and older ways of tracking things, not quick.

Turning our back on data would remove any outside accountability, leave policymakers driving a car without map or road, and lead the country to a place where the titillation of conspiracy and cherry-picked numbers become the only barometer of what’s real.

This year, we came closer to that point than any time I can remember.

_____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Abby McCloskey is a columnist, podcast host, and consultant. She directed domestic policy on two presidential campaigns and was director of economic policy at the American Enterprise Institute.

_____

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments