Andreas Kluth: The White House is using Africa as a MAGA prop

Published in Op Eds

First, South Africans were the ones baffled by the bizarre sounds coming out of the White House. Now it’s Nigerians’ turn. And other Africans may be next.

Out of the blue, President Donald Trump claimed over the weekend that in Nigeria “they’re killing the Christians and killing them in very large numbers. We’re not going to allow that to happen.” Trump added that he was instructing the Department of Defense to “prepare for possible action” and threatened that “if we attack, it will be fast, vicious, and sweet.”

Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa and a kaleidoscope of ethnicities and tribes that is religiously split roughly half Christian and half Muslim. Many Nigerians do suffer horrendous violence. In the north, where terrorist groups such as Boko Haram are active, the population skews Muslim, as do the victims. In the south, where herders often fight with Christian farmers, more victims are Christian. But it’s absurd to suggest that Nigeria as a nation is going after Christians.

Trump’s narrative about South Africa has been similarly distorted and puzzling. He kicked things off in February with an executive order that cut off all American aid and announced the fast-tracked resettlement of Afrikaners (Whites of largely Dutch descent) from South Africa to the U.S. His stated reason was that this group was facing “government-sponsored race-based discrimination” by the Black majority. He then expelled South Africa’s ambassador.

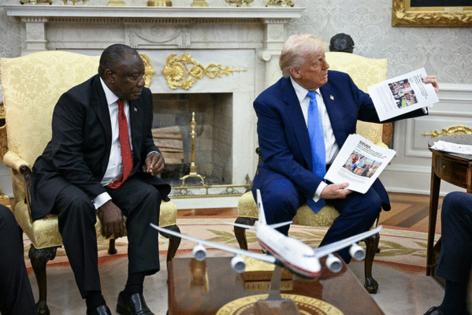

In May, Trump turned up the heat another notch when he hosted — or rather ambushed — South Africa’s president, Cyril Ramaphosa. Ramaphosa had come to the White House hoping to talk trade and business but was instead accused of overseeing a White genocide. At one point, Trump rolled lengthy footage and brandished reams of paper that allegedly provided evidence but were either taken out of context or identified as images from the Democratic Republic of the Congo rather than South Africa.

Ramaphosa stayed remarkably poised throughout his ordeal. (Unlike the Ukrainian president, who had suffered a similar ambush in the Oval Office, he even stayed for lunch.) But the South African government couldn’t reverse the narrative — White genocide, basically — that the White House and its MAGA base have settled on. So the bilateral relationship keeps deteriorating and altering America’s role on the continent and in the world.

The other day, the administration announced that it was shrinking the quota for admitting refugees from war zones worldwide — places such as Sudan and Myanmar — from 125,000 during the last fiscal year to 7,500 in the current one. But it is reserving most of those few spots for Afrikaners. When Democratic senators pressed Trump’s nominee for ambassador to South Africa on whether he agrees with Trump’s race-based refugee policy, he evaded the question.

In both Nigeria and South Africa, Trump is deliberately peddling “false narratives,” Witney Schneidman told me. He was an Africa expert at the State Department and is now at the Brookings Institution, a think tank.

South Africa does have an epidemic of crime — but it hurts Blacks even more than Whites. The country also does have policies that favor Blacks, and some of those, such as a recent law that allows expropriation (similar to “eminent domain”), are controversial even in South Africa. But the reason for this affirmative action (in U.S. parlance) was the country’s effort since 1994 to try to right the injustices and discrimination of the apartheid era, when Whites had land, wealth and opportunities, and Blacks didn’t.

In all those ways, post-apartheid South Africa, which calls itself “the rainbow nation,” is the perfect international bogey for the Trump administration, said William Gumede, a professor of governance at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. “I’m now using American terms,” he told me with a chuckle: “We’re the country with the biggest DEI agenda, the wokest country.”

As Chana Joffe-Walt, an American journalist of South African extraction, puts it in her profile of Afrikaners, to the MAGA movement South Africa is “a cautionary tale, a place where White people can no longer be safe, where the tables have turned, where they’ve gone too far.” The lesson Trump wants to emphasize at home, she adds, is that “a rainbow nation only ends in disaster.”

This insight points to a salient theme of U.S. foreign policy under Trump, which is the blending of domestic politics and foreign policy to the occlusion of the latter. Cameron Hudson, an Africa expert who used to be in the State Department and the National Security Council and is now at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told me that the message that the Trump administration will defend “Whites or Christians anywhere in the world” comes from deep within the MAGA movement and is aimed at it.

That explains why advisers such as Stephen Miller, who nominally has a domestic beat (homeland security), have at least as much input into foreign policy as the likes of Marco Rubio, the secretary of state and national security adviser. In this way, Trump’s Africa policy resembles his approach to Venezuela and other places: It’s about “America First” at home, not about actually putting America first in geopolitics today and tomorrow.

Here’s how a strategic foreign policy toward Nigeria, South Africa and the whole continent could look:

It would recognize that the relationship will always be tense and ambiguous, in part because of history. South Africa’s ruling party, Ramaphosa’s African National Congress, still holds a grudge against Washington for condoning apartheid during the Cold War, which is why it remains cordial with Moscow (which supported the ANC during apartheid) as well as Beijing, Tehran and other American adversaries. The U.S. also doesn’t like South Africa’s role in, say, accusing Israel of genocide at the International Court of Justice, or in building the BRICS forum (in which South Africa is the S) into a counterweight to a U.S.-led West.

Simultaneously, though, Washington would realize that Africa — like Indonesia, India, Brazil and other populous nations in the so-called Global South — is a potentially crucial swing state in the new Great Game of power politics, which pits China and its partners against the U.S. and its allies. That’s why Russia and China are investing hugely in Africa to gain influence at the expense of the U.S. Why should Washington help them and hurt itself?

But that’s what is happening. By alienating much of Africa, the Trump administration has “accelerated a move toward an anti-American multipolar order,” Gumede told me. That wasn’t the objective of Trump’s foreign policy, mind you. It’s merely the consequence of thinking small rather than large, domestically rather than strategically. It’s the result of treating the whole world as though it were a prop in Trump’s next MAGA rally.

_____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andreas Kluth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering U.S. diplomacy, national security and geopolitics. Previously, he was editor-in-chief of Handelsblatt Global and a writer for the Economist.

_____

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments