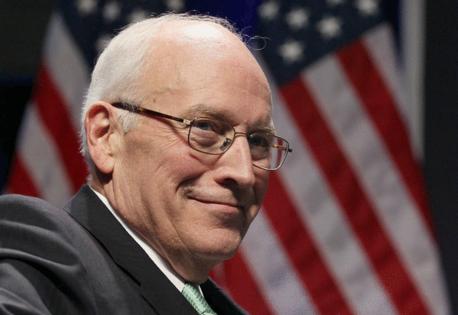

Martin Schram: Dick Cheney – reflecting on the unseen

Published in Op Eds

The president’s chief of staff was talking with aides outside his president’s waiting motorcade when he spotted me – and immediately began walking purposefully toward me for what figured to be one of those tough, and probably angry, confrontations.

Reporters know we can expect that when what we have written displeases the folks we cover. And as Newsday’s Washington bureau chief, I had just reported, with excruciating accuracy, the details of President Gerald Ford’s visit to Auschwitz, on July 29, 1975, along with the details of what Adolf Hitler’s Nazis had done there to adults and children who had committed the crime of being Jewish in Hitler’s Germany (a fate I was spared only because I was born in the U.S.).

I reported in Newsday how world leaders had spent hours visiting Auschwitz, somberly reflecting at this place where humans methodically committed inhumanity. I had reported that Ford’s advance team originally scheduled him to spend just three minutes at Auschwitz, helicoptering into the death camp, bestowing a wreath, signing a guest book, and helicoptering out.

I reported I’d seen Poland’s Communist Leader Edward Gierek urge Ford to extend his visit – and Ford glanced at Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who nodded OK. So Ford extended his visit 20 minutes. My Newsday article also reported a presidential aide’s explanation that Ford didn’t have time to visit the Auschwitz museum because it was too far away. “It is about 120 seconds away by automobile,” the article reported.

As Ford’s chief of staff reached me, I was frankly thinking there was no way he or Ford had time to know what I’d written in that article (at that moment it was just being read by folks in New York’s Long Island). I was so wrong.

Ford’s chief of staff, Dick Cheney, told me he had shown a copy of my Newsday article to “The Boss” (that would be Ford). So, of course, I was just bracing for the tirade-to-come. And this is what I got:

“We really f---ed that up. We were wrong and we’re sorry. We deserved what you wrote. See you around.” Then Cheney left, presumably to tell his boss he’d delivered their joint message.

I thought of that moment when news broke about Cheney having died Monday night of pneumonia, after his years of severe cardiac issues. You of course have come to know Cheney by his reputation as a tough, no-nonsense hardliner. And on national defense issues, Cheney was just that. But he was also far more.

Let me tell you a bit more about this Wyoming politician. We met shortly after he arrived in Washington. In 1969, I was covering the new presidency of Richard Nixon and arrived at the White House for an interview with Donald Rumsfeld, a former Illinois congressman, who was a Nixon domestic policy adviser. Rumsfeld began by saying he’d asked a new fellow on his staff to sit in – just to see how he handles interviews. The new guy – Cheney – had just arrived and parked his Volkswagen Beetle between the long black limos parked along the gated street beside the West Wing.

That was the day we basically began a working friendship – built on mutual respect of two guys who often disagreed on life’s minor things, such as issues.

Cheney rode a rocket to the peak of Washington power – and ended feeling the pique of power. When Rumsfeld became Ford’s presidential chief of staff, Cheney became his deputy. When Rumsfeld became secretary of defense, Cheney got Rummy’s old chief-of-staff job. Next he became Wyoming’s congressman, then President George H. W. Bush’s secretary of defense and President George W. Bush’s vice president.

And that was when he became forever linked as an architect of G.W. Bush’s controversial invasion of Iraq. Just days before that order was given, I was in a suburban Bethesda, Maryland Safeway when I saw a familiar figure ahead of me in the aisle.

I said hi to retired Gen. Brent Scowcroft. And in a classic Washington switcheroo, the man who’d been Ford’s and H.W. Bush’s national security adviser and friend asked the journalist: “Marty, can I ask you something off the record?” I granted him permission.

Scowcroft had just written a now-famous Wall Street Journal opinion piece urging G.W. Bush not to invade Iraq. Washington’s cognoscenti understood Scowcroft’s powerful warning against invasion as being a de facto effort by a reserved and hugely worried president/father to give advice to his president/son.

Scowcroft, who served as national security adviser alongside Cheney in the Ford and H.W. Bush presidencies, said he didn’t understand why Cheney, as veep, was pushing so vehemently to invade Iraq. He thought I knew Cheney well and asked, simply: “Why?”

I didn’t have inside info – but I had one thought. Perhaps Cheney’s cardiac issues had made him feel time is precious – this needs to be settled right now! As a stalwart patriot, he hoped to guide things to a favorable outcome. Scowcroft thought for a minute, then said that was the first response he’d gotten that was founded in respect and made sense. But we never knew for sure.

Meanwhile, I have one lasting memory that I consider defining: On the first anniversary of the MAGA/Trump January 6 violent invasion of the Capitol, only two Republicans sat on their party’s side of the aisle as the House of Representatives marked the occasion – former Rep. Dick Cheney and his daughter, then-Rep. Liz Cheney. Once again a father and daughter caught up in a crisis and caring as patriots and parents do.

R.I.P., old friend.

_____

_____

©2025 Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments