Commentary: When Darrow took on Bryan 100 years ago, science got the win. Or did it?

Published in Science & Technology News

Before O.J. Simpson’s “trial of the century,” another courtroom clash riveted America and merited that title. In the sleepy town of Dayton, Tenn., on July 10, 1925, the Scopes “Monkey Trial” was gaveled to order. The issues contested in the second-story courtroom of the Rhea County courthouse may seem long settled, but they still divide Americans 100 years later.

At the behest of the American Civil Liberties Union, a young science teacher, John T. Scopes, agreed to stand trial for violating Tennessee’s Butler Act, which forbade educators “to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.”

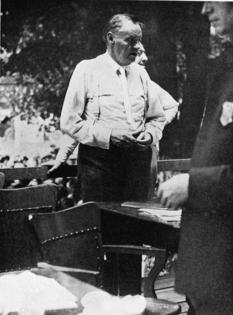

Local boosters in Dayton calculated that a trial pitting science against religion would provide a jolt to the town’s economy. William Jennings Bryan, fundamentalist Christian and three-time Democratic nominee for president, agreed to assist the prosecution, and Clarence Darrow, agnostic and arguably the nation’s most famous defense attorney, signed onto the Scopes team. WGN, the clear-channel radio station in Chicago, carried the proceedings live, and the irascible H.L. Mencken of the Baltimore Sun led the phalanx of journalists who descended on Dayton.

For eight days, Dayton was awash in visitors, including journalists, partisans on one side or the other and chimpanzees. Banners advocated Bible reading. Lemonade stands popped up. Nearly a thousand people crowded into the courtroom, and even more witnessed the proceedings when they were moved outside because of the summer heat. Over Darrow’s objections, the Scopes trial opened each day with prayer.

The trial was supposed to decide a narrow question: Had Dayton’s high schoolers been taught evolution; was the Butler Act violated? The judge quashed various defense attempts to contest the merits of the act, but that didn’t stop the trial from unfolding as a a proxy for larger issues. Bryan posited that “if evolution wins, Christianity goes,” and Darrow countered with “Scopes isn’t on trial; civilization is on trial.” He added that the prosecution was “opening the doors for a reign of bigotry equal to anything in the Middle Ages.”

Once the judge refused to hear testimony from most of the defense’s Bible and science experts, Darrow called Bryan to testify as an expert on the Bible. The New York Times described what ensued as “the most amazing court scene in Anglo-Saxon history.”

“You have given considerable study to the Bible, haven’t you, Mr. Bryan?” Darrow began. Bryan replied that he had studied the Bible for about 50 years. Darrow proceeded with a fusillade of “village atheist” challenges to famous Bible stories: Jonah and the whale, Noah and the great flood, Joshua making the sun stand still. Bryan, who had initially insisted that “everything in the Bible should be accepted as it is given there,” had to say time and again that he’d never questioned the biblical accounts. He eventually conceded that the Genesis account of creation might refer to six “periods” rather than six 24-hour-days.

The exchange grew testy. Bryan complained that Darrow was trying to “slur at the Bible” and declared that he would continue to answer Darrow’s questions because “I want the world to know that this man, who does not believe in God, is trying to use a court in Tennessee ...” but Darrow interrupted. “I object to your statement,” he thundered, and to “your fool ideas that no intelligent Christian on Earth believes.”

The outcome of the Scopes trial was never in doubt. The jury of 11 white men, all but one of whom attended church regularly, returned a guilty verdict after nine minutes of deliberation. Scopes was fined $100 (a verdict later overturned on a technicality). Bryan, a broken man, died in Dayton five days later.

Most liberals, theological and political, believed that science and common sense had prevailed once and for all in that steamy Tennessee courtroom, that Darrow had banished the retrograde “fool ideas” of Christian literalists to the margins. But is that true?

Although it was never enforced again, the Butler Act remained on the books in Tennessee until 1967. Some publishers, afraid of a backlash from churchgoers, quietly expunged or watered down evolution in their textbooks, and many states continued to prohibit the teaching of evolution in public schools. That added to an alarming decline in science education in the United States, a deficit that came finally to public notice when the Soviets launched their Sputnik satellite in 1957. President Kennedy’s aspirations to land a man on the moon jump-started American science dominance education in the 1960s, which necessarily rested, in part, on the fundamentals of Darwin’s evolutionary theory.

But many of the faithful remained wary. Several organizations emerged in the 1960s and 1970s — the Creation Research Society, Bible Science Assn., the Institute for Creation Research, among others — that advocated “creationism” and later, “scientific creationism,” a sometimes comic attempt to clothe biblical literalism with scientific legitimacy. Most scientists scoffed, dismissing as preposterous claims that the Grand Canyon, for example, was formed in a matter of weeks.

Courts repeatedly refused to countenance creationism as anything but religious teaching and therefore impermissible in public schools because of the establishment clause of the 1st Amendment (“Congress shall make no law respecting the establishment of religion …”). Undeterred, “Bible-believing” Christians set about inventing new guises for creationism, which led to something called “intelligent design,” the notion that creation is so ordered and complex that some Designer must perforce have initiated and superintended the process.

The legal showdown over intelligent design took place in Dover, Pennsylvania, where the school board had required biology teachers to read a statement asserting that evolution “is not a fact” and urging students “to keep an open mind.” John E. Jones, U.S. district judge appointed to the bench by President George W. Bush, ruled in December 2005 that intelligent design was “a mere re-labeling of creationism and not a scientific theory,” and that requiring it in public schools represented a violation of the establishment clause.

Even now those who can’t abide Darwinism are very likely working on the next evolution of creationism. In the meantime, the broader religious right mounts attacks on science and public education that echo those that animated the Scopes trial. Public education, one of the cornerstones of democracy, is itself on the line, as religious nationalists support the diversion of taxpayer funds to provide vouchers for religious schools. Sadly, the current Supreme Court, with scant regard for the establishment clause, is abetting those efforts.

The Bible vs. Darwin showdown in Tennessee cast a long shadow over American life. The jury may have taken only nine minutes to determine the fate of Scopes, but 100 years later science and religion, and modernism and fundamentalism are still fighting it out.

_____

Randall Balmer, a professor of religion at Dartmouth College, wrote and hosted three PBS documentaries, including “In the Beginning: The Creationist Controversy.” His latest book is “America’s Best Idea: The Separation of Church and State.”

_____

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments