Get ready for a tarot map of trauma, power and reclaimed lineage

Published in Mom's Advice

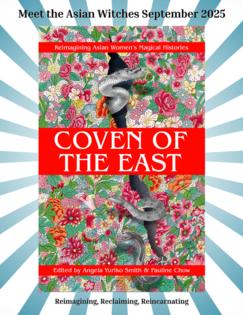

Every anthology has to choose its organizing principle, but few feel as alive as the one guiding "Coven of the East: Reimagining Asian Women’s Magical Histories." Editors Angela Yuriko Smith and Pauline Chow map the 22 entries against the 22 Major Arcana of the Rider–Waite–Smith tarot. It’s a clever structure, intuitive, almost organic, as if the stories existed before and were waiting for the right deck to draw them together.

Beginning with "The Fool" and ending with "The World," the collection reads less like a random assembly of stories and more like a ritual. The reader is invited into a journey that arcs from innocence to completion, discovery to integration, silence to full-throated song.

That framing matters because this book is not only about magic but about reclaiming erased lineages of power. The pieces insist that Asian women have always been mediators between the visible and invisible, whether as nǚwū in China, mudangs in Korea, or yuta in Okinawa. Systems like Confucian orthodoxy tried to erase them, demonize them, or reduce them to quaint folklore. This anthology answers back, saying no, these women were never marginal. They were central. They still are.

The anthology is at its most electrifying when it directly addresses the cost of enforced silence and the rupture that occurs when voices finally rise. Lee Murray’s “Hush” crystallizes this tension. She writes of witches who have long contained pain in quiet, holding the traumas of violated girls in nets of secrecy for the sake of survival. But survival is not the same as living and Murray insists on a new song, one that rejects complicity. That shift — breaking the hush, speaking the unspeakable — is the revolution at the heart of the book.

Other pieces extend this theme in startling ways. Wen Wen Yang’s “Once Upon a Time a Skeleton in the West” transforms Baigujing, the demoness weakened by Sun Wukong, into an avenger stalking traffickers. The violence is righteous, a deliberate rejection of victimhood, as the demoness turns her skeletal body into an instrument of justice. Mudang Jenn’s “Submission,” meanwhile, reminds us that true submission is not to oppressive structures but to the sacred vessel of the body itself. By returning to Ungnyeo the Bear as the ancestral mother of Korean shamans, she reclaims a story stripped of its feminine power.

What links these stories is the insistence that silence protects no one. Coven of the East gives us women who howl, chant, cook, sing and invoke … and in doing so, they shift entire worlds.

If there is a single spell being cast across these 22 pieces, it is the alchemy of transforming trauma into power. That idea runs like a current, whether it appears in small, intimate forms — like a mother sacrificing her essence to keep her sick child safe in Ai Jiang’s “A House That Cannot Fall” — or in vast, cultural expressions such as Chaweon Koo’s “Bewitched by K-Pop.” Koo reframes K-Pop not as an industry trend but as a survival ritual, the most successful magical operation Korea has ever performed. Light sticks become wands, fan chants become invocations, choreography becomes spellcasting and all of it is fueled by Han, the collective grief and fury transmuted into spectacle and strength.

This process of transfiguration is not always clean or comfortable. T. S. Ren’s “We Feed the Hungry Ghost” lingers on cycles of abuse, showing how even when fathers are reduced to wraiths, their cruelty echoes. Kristy Park Kulski’s “Don’t Forget Me” uses the figure of a grandmother to reveal that sometimes the ghost is you, still tethered to unfinished business. Yet even in these painful turns, there is resilience, a refusal to let suffering remain mute. The stories argue that memory itself is a kind of spell and survival is the purest form of sorcery.

What elevates "Coven of the East" is its ability to balance personal narratives with mythic resonance. Recipes carry the taste of ancestral resilience, dolls deliver violent justice, hair becomes a shapeshifter’s mask and tigers prowl through poems as guardians of the disabled and the weary. These are living emblems of survival and transformation.

By the time the anthology closes with Sonya Rhen’s “Dreams of a Large Oak Tree,” the reader understands that what has been built here is not just an anthology but a lineage. Dreams, prophecies and ancestral whispers refuse to be silenced. The tarot journey ends, but the reverberations continue.

"Coven of the East" is a reclamation, an incantation and a dare. It asks you to believe in what has been hidden and to honor the women who carried those truths despite systems that tried to bury them. More than anything, it insists that silence is over.

Comments