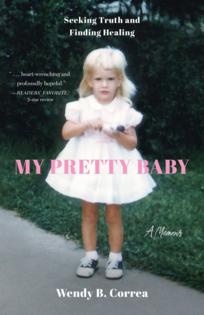

Belonging after brokenness: One woman’s search for truth and healing

Published in Mom's Advice

Wendy B. Correa’s new memoir "My Pretty Baby: Seeking Truth and Finding Healing," details a fascinating life defined by resilience and accomplishment in the face of childhood trauma and a dysfunctional family environment. As Correa deftly shows in this writing debut, life is not so much about what happens to you as it is what you do with what happens to you.

Organized into three sections — Being, Becoming and Belonging — the book constitutes a broad and satisfying reflection on a young woman’s deep-seated determination to fashion a purposeful life.

The story opens when Wendy is 7, with her 45-year-old father’s unexpected death. In some of the most poignant words in the book, she explains how no one takes the time to listen to her fears and calm her down.

“No one said it was very sad that my dad had died … No one said that we would miss him very much … No one said he loved me very much and was very sorry he would not get to see me grow up. No one said we could see him in the moon and the stars, and that I could always talk to him … No one said that I needn’t worry — that even though my father had died, my mother was healthy and young and would not die. No one said that … we would grieve properly, and missing him would hurt, but we would all be okay.”

Instead, she’s urged to appreciate his last Christmas gift to her: a Barbie dollhouse he made himself — even though Wendy had never liked Barbie dolls. She’s more consoled by seeing that Caroline Kennedy, same age as Wendy, has just lost her father.“I thought the two of us belonged to a special club of little girls who had lost a father. For many years, I thought that Caroline and I were the only members of that club.”

Growing up in a suburb of Chicago, Wendy is youngest of three, but her siblings offer little. Her sister resents her from birth for reasons Wendy eventually explains, and her brother retreats early on into his Christian faith. Wendy never stops adoring her mother, but her mother’s often hurtful actions evidence their complex relationship.

The man who soon becomes Wendy’s stepfather, Paul, enters her life when she is nine; he is “ a handsome, raven-haired, 34-old Marlon Brando type — a tough-guy character.” Their first Christmas together, he lunges for the Christmas tree in a fit of rage and alcohol, throws it to the floor, threatens to kill everybody in the room, and manhandles her mom and brother. In what becomes the norm every time Paul erupts, her mother sends the kids to family members.

While he never learns to manage his rage, this same man takes Wendy and her mother on wonderful trips to Colorado every summer, buys Wendy thoughtful presents, like an LP of The Mamas & the Papas, and calls her his daughter. As Wendy says,“I was already learning at this tender age that human beings are complicated, unpredictable creatures with good and bad traits.”

After a childhood in “suffocating, depressing, dead-end Forestville, where none of my friends planned to go to college or do anything to learn and improve their lives,” Wendy earns two bachelor’s degrees and joins the music industry, first representing folk-rock artists in a talent agency and then as a DJ in Colorado.

It makes sense since, in her words, “music had raised me.” But her family situation stays unresolved.

When her sister suggests that the man Wendy has assumed to be her father is not, Wendy pays attention. Is this her sister being mean again? Or is there more? Wendy yearns to find out. “I thought of the words of Baba Ram Dass: ‘If you think you are enlightened, go spend a week with your family’ … Now there was a man who knew what he was talking about.”

For healing and to address her numerous addictions, Wendy immerses herself in psychotherapy, AA and various religious views dissimilar to the traditional Christian churches of her childhood, and her experiences deeply enrich the story.

We learn the Native American phrase mitákuye oyásin, a Lakota phrase meaning we are all related, so that when one entity — person, animal, plant, elemant of nature, spiritual realm — suffers, all are harmed. And it leads to Wendy finding love and motherhood and a career in the healing fields.

The memoir finishes with the words of sociologist Brené Brown: “When we deny our stories, they define us. When we own our stories, we get to write a brave new ending.”

"My Pretty Baby" not only bears witness to an articulate, sensitive and ambitious woman’s difficult path to her own brave new ending; its healing perspective may well inspire our own brave new ending.

____

Comments