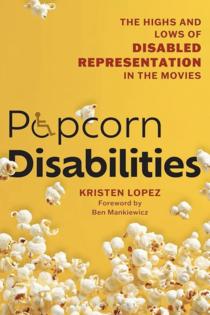

'Popcorn Disabilities' author Kristen Lopez looks at disability portrayals in movies

Published in Books News

In her new book “Popcorn Disabilities: The Highs and Lows of Disabled Representation in the Movies,” film critic and author Kristen Lopez says she wasn’t interested in writing “an academic book or one that felt like eating your vegetables.”

Even so, some publishers were skeptical.

“It’s not a sexy topic, which I’m aware of!” she says. “I wanted to write something that people can read where they’re not going to feel judged and can laugh a little. But also where I can talk about how movies have shaped a generation of disabled viewers — how these stereotypes leap off the screen and can hit the person watching them, and I use myself as the example. I talk about how these movies have affected me and how I see myself.”

A wheelchair user, Lopez talks about her frustration watching disabled characters played by abled actors, especially female characters.

“The disability is directly tied into how she looks. You don’t want to mess with the face, so you get a lot of blind, deaf, nonverbal performances, what I call ‘pretty disability.’ When you do see a wheelchair user, the woman is 5’6” and she’s sitting and she could pass for abled. For me, growing up, I couldn’t pass for abled. I’m not proportionate, I’m very small, I’m very compact. And growing up I was like, if these women have problems finding love and going about their lives and they’re beautiful women, what the hell does that mean for me? I don’t see anybody that looks like me!

“Most women that are disabled in films, who aren’t conventionally aesthetically attractive, are monsters,” she adds. “I talk in the book about my fear growing up of Zelda in ‘Pet Sematary ’ (1989) because she looked more like me than someone like Jane Wyman in ‘Johnny Belinda’ (1948). So when you’re a young girl and already dealing with beauty standards in terms of weight and makeup and all of the ways that you can look attractive, if you’re a disabled girl and you’re watching movies about disabled women? You’re like, well, I don’t look like that, so I guess I’m unattractive and I shouldn’t exist. I worry about the next generation of disabled girls, because they don’t have something better.”

The book also includes chapters on mental and cognitive disabilities in film, a reluctance to acknowledge the way racism can complicate a disabled person’s experiences in the world, and whether abled actors playing disabled characters is a blatant play for awards.

We talk more about Hollywood’s conception of disabled people.

Q: There’s a phrase you use throughout the book, which is the Tiny Tim principle. Explain what that is.

A: Tiny Tim is the one that screwed it up for everyone! He’s obviously the character from “A Christmas Carol” and he’s kind of the de facto definition of what a disabled person is, where you have a character that’s disabled and therefore sickly, but he has such a good heart. His soul is pure. And through his purity and goodness and unselfishness, he is able to teach the miserly Scrooge how to be a good person. And that was something that set the tone for shaping the belief that disabled people were children in need of caring.

So that extended to movies more generally, where disabled characters are always good and almost saintly and they help teach able-bodied people how to be good people.

Q: In the book, you talk about the idea that what we see on screen often shapes how we understand or think about the world.

A: Culture influences movies, and movies have the ability to influence culture. I’ve had so many personal experiences with people where they feel that they understand me or understand my life because they’ve seen a movie.

Q: Let me push back a little. Isn’t that one of the things we love about the movies — that they give you a window into someone else’s experience?

A: They do! But at the same time, if the representation is bad and you don’t know that, then the bad representation becomes solidified as truth. That’s the problem. Unless you’re an active viewer and want to take the time to research and maybe read a book about it, you’re probably going to believe certain things that a movie is espousing, and movies codify ideas that trickle down into people’s perceptions of disability.

A lot of people who have met me are like, “You have sweet government money! The government pays you as a disabled person.” And I’m like, where do people get that idea? Movies don’t even discuss the issues inherent in the Social Security disability insurance system. And as I was watching movies for the book, I realized how often disabled characters are financially well-off or at least comfortable. We never see disabled characters struggle for money. But a lot of that is because the movies situate the character as being cared for by somebody — a wife or their parents — and movies don’t discuss how disabled people make money, or even have jobs.

Another example was watching David Gordon Green’s film “Stronger” (2017) with Jake Gyllenhaal, which was really kind of eye-opening because it was the first time in a long time I had seen a disabled character living in a house that was not designed for a wheelchair. And watching that character struggle to move around, to transfer to a toilet in a small bathroom, to transfer into a car — these moments are not big moments, but the fact that Green shows them is kind of amazing because I still meet people who are shocked that I can drive a car, because they’ve never seen it. And if you’ve never seen it and you don’t interact with disabled people, then, yeah, you’re not going to know that we can drive cars.

Q: Is there a stigma against hiring disabled actors?

A: There definitely is. Marissa Bode, who plays Nessarose in “Wicked” has talked about the fact that we still have abled actors “cripping up,” which is the terminology for when abled actors play disabled characters. I come at it from a slightly different perspective because I am an entertainment journalist and I understand, OK, butts in seats and movie stars sell.

In 1932, when Todd Browning does the horror-drama “Freaks,” it sets up this idea that disabled actors are inexperienced and can’t act and therefore can only play themselves. So if a movie doesn’t call for a disability, why would you hire a disabled actor?

Q: Let’s talk about disability in the horror genre.

A: Horror has always been hospitable to the disabled, I think, because monsters are coded that way, going back to the Boris Karloff version of “Frankenstein” (1931).

But horror movies also often have disabled lead characters and disabled women, in particular. I love the Chucky films; actress Fiona Dourif is not a disabled woman, but the character uses a wheelchair and the director Don Mancini spends time showing you how she cooks, how she navigates space. A criticism of the premise is that Chucky is 3 feet tall, you could just kick him, and Mancini’s like, wouldn’t it be great to look at a heroine who wouldn’t have that ability? And the way that she gets out of situations is really inventive and it’s great to see that she’s not a victim. That she’s not a helpless damsel waiting for an abled person to save her.

Q: What’s one film you think captures disability well?

A: I love “Coming Home” from 1978. It’s the story of a Vietnam vet, played by Jon Voight, who is a wheelchair user who is trying to find his way in a world of changing political morals, and being a disabled man, and he falls into a relationship with a woman, played by Jane Fonda, who is the wife of another vet. There are some abled actors who have done an amazing job playing disabled characters and that’s true here. I love the bits of business, like the way Voight wheels the wheelchair, the way that he moves through space. It feels authentic.

Q: Also, he’s a sexual character and I feel like most depictions of disabled people tend to be asexual.

A: And if you’re a woman? Don’t expect to have sex at all. But yeah, “Coming Home” has a beautiful sex scene that’s hot regardless of the disability or not. And it’s a sex scene where the sexiness is in their communication. There’s a lot of discussion around, what’s going to work for him and “are you comfortable?”

Q: What’s one film that makes your skin crawl with its depiction of disability?

A: There are so many, but the one I always go for is “Me Before You” (2016) with Emilia Clarke and Sam Claflin. He plays a wealthy wheelchair user who lives in a castle and he is a curmudgeon who wants to kill himself because he doesn’t want to be disabled anymore. His family hires him an unqualified caregiver played by Clarke, who flirts with the line of being a sex worker. The hope is that he’ll fall in love with her and not want to kill himself. It’s based on a romance novel and it always makes me mad. I’m like, dude, you have nothing to complain about, you live in a castle, you have a tricked out van so you can go wherever you want and you’re still not happy.

And it sets a bad precedent for caregivers of disabled people. If you’re a woman, what’s the line between sex work and caregiving? That’s a thing that happens way too much in these types of movies. And the fact that she doesn’t listen to him; there are so many scenes where he tells her, as a wheelchair user, what works for his experience, and she’s like, “You don’t know!”

It’s just so stereotypical that disabled people are angry about their disability, but also financially well-off and are just waiting for their turn to die. It never ceases to piss me off.

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC. ©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments