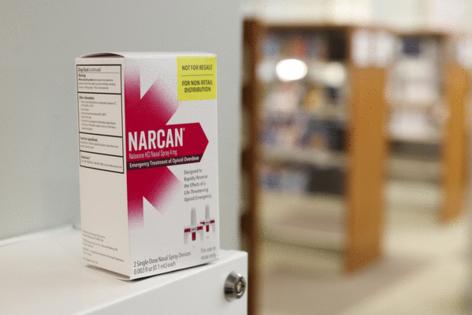

New law requires public libraries across Illinois to carry opioid OD reversal medication

Published in News & Features

Rob Simmons estimates that, over the last decade, Oak Park Public Library employees have helped save the lives of about 20 people who overdosed on opioids.

In some cases staff members saw that a patron had potentially overdosed in the library and called 911. In other instances, staffers administered a naloxone nasal spray that can reverse the effects of opioid overdoses, he said.

Opioid abuse among library patrons is “a real challenge and an unfortunate reality,” said Simmons, director of social services and public safety at the Oak Park Public Library. “I think to have an intervention available on-site that can save lives is crucial.”

Though many Illinois libraries, like Oak Park’s, already have supplies of medications that can reverse opioid overdoses, a new state law will soon require all public libraries to stock them. The new law, which takes effect Jan. 1, also instructs libraries to take “reasonable steps” to make sure there’s always a staff member present who’s been trained in how to recognize and respond to opioid overdoses.

“We know opioid antagonists like Narcan, if administered when someone is having an overdose, can be very effective in preventing someone from dying from an overdose,” said state Rep. Anna Moeller, an Elgin Democrat, who sponsored the bill behind the law.

“Libraries are public places,” Moeller said. “You have a lot of people who are there. It could be a place where somebody might be having an emergency like that.”

The new law shouldn’t cost libraries anything, as they can get free opioid antagonists and training through the state, Moeller said. Earlier this month, the Illinois Department of Public Health also issued an updated standing order, clarifying that libraries can get opioid antagonists without a prescription, to make it easier for libraries to comply with the new law.

Moeller got the idea for the measure from Jordan Henry, a teen who worked on the concept as part of a school project at the Illinois Mathematics and Science Academy.

Henry — a frequent library patron herself — had heard about Chicago Public Library locations keeping opioid antagonists on hand and wondered why more libraries couldn’t do the same.

“Libraries are such a huge part of the community,” said Henry, who’s now a freshman at Loyola University Chicago. “They’re free, they’re open most days of the week. They’re usually in very centralized locations. … There’s so many across the state, so it’s easier for people to reach them regardless of circumstances.”

Henry’s mother was at an event with Moeller at their local library in Elgin, where she heard that the representative wanted to work on bills with community members. Henry said her mother asked if she was interested, and after she said yes, they set up a meeting.

Henry said she initially thought they would work on extending opioid antagonists to just her local library, but Mueller suggested they go statewide.

Keeping supplies of naloxone on hand has made a big difference at the Oak Park Public Library, Simmons said. Since 2023, the library has had a red box on a wall near its entrance with naloxone that anyone in the community can take.

People frequently grab the medication, and the local health department typically replenishes supplies in the box a couple of times a week, Simmons said.

The library also keeps supplies of nasal sprays provided by Live4Lali in the public safety staff office, for those workers to use on patrons in emergencies. Live4Lali is an Arlington Heights-based group that works to prevent substance abuse and reduce harm from substance abuse.

Simmons estimated that about two or three people overdose at the library each year, often in the bathrooms.

The Evanston Public Library also has a box on the wall with naloxone sprays for community members to take freely, said Ellen Riggsbee, marketing and communications manager for the Evanston library.

In anticipation of the new law, the library also acquired supplies of naloxone to be used specifically by staff in emergencies.

So far, about two-thirds of the library’s staff has been trained on how and when to use opioid antagonists, Riggsbee said. They’re learning about how to respond to potential overdoses.

For example, if a patron is passed out, a staff member may tap on a table or nearby surface to try to rouse the person, Riggsbee said. If the person doesn’t wake, the staffer may ask for the library’s public safety staff to come over, and together they’ll look for signs of an opioid overdose, such as blue nails or breathing that’s slow, irregular or stopped.

If the signs are there, after calling 911, staff members may retrieve one of the library’s nasal sprays, and administer a dose in hopes of potentially saving the person’s life, Riggsbee said.

“We know this is just a realistic part of a library’s work,” Riggsbee said. “It’s a public library and we have to ensure the safety of everybody who comes in.”

The O’Fallon Public Library, near St. Louis, has had supplies of naloxone for about five years, said Ryan Johnson, the library’s director.

The naloxone is part of the library’s regular first-aid kits, with one kit on the first floor and another on the second floor.

Staffers haven’t had to use the naloxone yet, but Johnson, who is also a past president of the Illinois Library Association, is glad to have it on hand.

“You put it in your toolbox and hopefully you never have to use it, but if you do, you’ve got it and you can potentially save someone’s life,” Johnson said.

_____

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments