Mammograms may reveal hidden heart risks for women, Penn State study finds

Published in News & Features

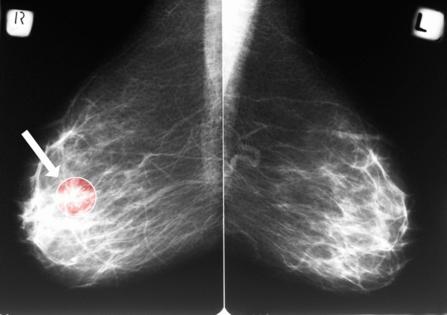

Routine mammograms are best known as a front-line tool for detecting breast cancer. But new research suggests the same X-ray images may also offer an early warning sign for cardiovascular disease — the leading cause of death among women.

A study presented at a Dec. 3 Radiological Society of North America meeting found that calcium deposits visible in the arteries of the breast can help predict a woman's future risk of heart attack, heart failure, stroke and death. The findings add to growing evidence that mammograms may hold untapped value beyond cancer screening.

The condition that mammograms can detect — and act as an early warning of heart problems down the road — is called breast arterial calcification, said Matthew Nudy, an assistant professor of medicine and public health sciences at Penn State College of Medicine who presented the findings.

Breast arterial calcification, or BAC, is relatively common, appearing in an estimated 15% to 25% of screening mammograms. Yet it is not routinely reported.

Despite often being discernible on routine mammograms, radiologists do not typically report the presence of these calcifications "because there's no known association between this breast arterial calcification and breast cancer," Nudy said.

That omission may represent a missed opportunity — particularly for women, who often face delays in cardiovascular diagnosis.

More than 60 million U.S. women — about 44% — have some form of heart disease, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Heart disease can affect any age and is the leading cause of death for women across the country. In 2023, it was responsible for about 1 in 5 deaths, nearly 305,000 women, per the CDC.

In the new Penn State study, researchers analyzed data from 10,348 women who had undergone at least two mammograms at a U.S. academic medical center, with an average of 4.1 years between scans. Using an artificial intelligence tool, the team measured the severity and progression of calcification in breast arteries over time.

They found that nearly 1 in 5 women had detectable vascular calcification at baseline. More importantly, the severity and progression of that calcification mattered. Women with worsening calcium buildup faced significantly higher risks of major cardiovascular events — up to double the risk for those with the most severe scores, Nudy explained.

One of the most striking findings was how quickly changes could occur.

"We saw progression of this BAC, or breast arterial calcification, in as little as one year," Nudy said. "So I think it just goes to show that cardiovascular risk is something that changes all the time."

Women who initially showed no calcification but developed it later had a 41% higher risk of cardiovascular events and death over an average 5.6 years of follow-up. Risk climbed even higher for women whose calcification advanced from mild to moderate or severe levels.

Unlike coronary artery calcium scoring — a CT scan is sometimes ordered to assess heart disease risk — identifying BAC does not require additional testing, radiation or cost, Nudy pointed out.

Instead, the data already exist on routine mammograms performed for breast cancer screening.

If breast arterial calcification were routinely reported, Nudy said, the next step would not be panic — but evaluation.

"At the very least, these patients should have a cardiovascular disease risk assessment," he said, noting that this typically includes blood pressure and cholesterol checks, use of risk calculators and, when appropriate, preventive therapies such as statins, blood pressure medications and lifestyle changes.

The research may be especially relevant given long-standing disparities in women's heart health.

"We know that women face a lot of disparities when it comes to cardiovascular care, compared to men," Nudy said. "They're more likely to be diagnosed at later stages of cardiovascular disease ... and we also know that women are less likely to get" treatment for the condition.

Breast arterial calcification, he said, "could be something that we use to improve that."

One major hurdle remains: inconsistent reporting.

Currently, there is no standardized system for documenting BAC in radiology reports, although Canada has proposed a grading framework.

In this study, researchers used AI to quantify calcification efficiently across thousands of images.

"If we were to run a research study where we had to have multiple radiologists analyze multiple mammogram images from over 10,000 participants, that would take a lot of time and a lot of money," Nudy said. AI, he added, made the process scalable and standardized.

Still, important questions remain unanswered — including whether identifying BAC leads to meaningful changes in patient care and outcomes.

Further answers may be on the horizon. Nudy is leading additional research using mammograms from the federally funded Women's Health Initiative, one of the largest and longest-running studies of chronic disease in menopausal women.

For now, the findings highlight a new way clinicians may one day use an already familiar test — not just to detect cancer, but to help prevent heart disease before symptoms ever appear.

_____

© 2025 the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Visit www.post-gazette.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments