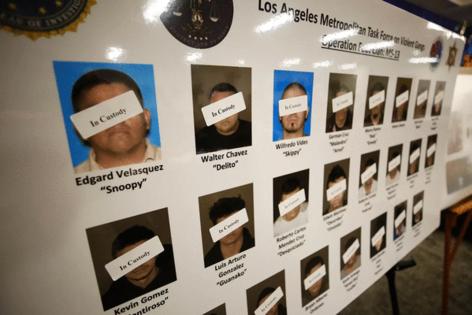

MS-13 gangsters used mountains around LA as killing grounds, prosecutors say

Published in News & Features

LOS ANGELES — The young men from MS-13 lived mostly in the cramped urban districts of Van Nuys, Panorama City and North Hollywood.

But it was in the mountains north and west of Los Angeles, where, as one alleged gang member put it in a recorded jailhouse sting, they went “to play.”

At a remote helipad and scenic overlooks, many miles from any witnesses or good Samaritans who might intervene, the gangsters — some just teenagers — killed four people between 2017 and 2019, Deputy District Attorney Eric Siddall told a jury Tuesday in federal court. The five alleged MS-13 members on trial were also charged with killing two people in Van Nuys and North Hollywood.

Also known as the Mara Salvatrucha, MS-13 was founded 40 years ago by Salvadoran immigrants in Los Angeles. It has since metastasized into an international criminal organization led by imprisoned gang members in Central America.

Over a two-month trial, prosecutors made the case that the local branches of the gang became far more violent around 2016. An influx of gangsters from Central America brought with them “the Salvadoran rules,” which required prospective members to kill to prove their loyalty, said Siddall, who was deputized to assist in the federal racketeering prosecution.

“The more ruthless the killing, the greater the respect that was earned,” he told the jury.

One victim was stabbed 107 times, while another was disemboweled while still alive, Siddall said.

Defense attorneys argued the prosecution’s cooperating witnesses — eight admitted killers who struck plea deals — lied in exchange for lighter sentences. Another lawyer for the accused compared MS-13 members with “child soldiers” who have been inured to extreme displays of violence.

One attorney said his client “did what he had to do” to survive.

“If you fail to follow an order to participate in a killing,” he said, “you’re next.”

The motive for all of the killings was essentially the same, Siddall said: The defendants spilled blood in hopes of being recognized as “homeboys,” or full-fledged members of MS-13.

The tangible benefits were negligible. Upon initiation, homeboys weren’t handed control of lucrative drug dealing or extortion rackets. The privileges amounted to being allowed to make MS-13 hand signs and having “paros,” lower-level associates, to “boss around,” the prosecutor said.

To hear prosecutors tell it, MS-13 members in Los Angeles were subpar racketeers but prolific killers. They shook down street vendors for chump change and sold marijuana, but their primary focus, Siddall argued, was seeking out enemies — rivals outside the gang and perceived traitors within.

A kill represented a chance for advancement. When the leaders of three MS-13 “cliques,” or subsets, decided to kill a man for throwing an unauthorized gang hand sign, Siddall said, 11 people took part in stabbing and hacking him to death in a kind of group initiation.

The victim was Elvin Hernandez, a doughy 20-year-old nicknamed “Winnie Pooh” who wasn’t in MS-13 but hung around people who were. In Facebook messages obtained by the FBI, a woman told a leader of the Park View clique that Hernandez was claiming membership in the gang. The clique leader said they’d hold “court” to judge and punish Hernandez.

The night of June 4, 2017, Hernandez was brought to a “destroyer” — MS-13’s term for abandoned homes where they live, party, sell drugs and kill — where the leaders of the Park View, Francis and Fulton cliques held a “roll call,” Siddall said. When it was Hernandez’s turn to introduce himself, he made an MS-13 hand sign.

The leader of the Fulton clique, Walter Chavez Larin, assaulted Hernandez and took away the machete he was carrying. Then everyone loaded up in two cars and drove Hernandez to the “Too Late” helipad in the Angeles National Forest, Siddall said.

Thinking he was only due for a beating, Hernandez laid face down before 11 people took turns stabbing him. According to Siddall, Chavez Larin told the dying man: “The Grim Reaper just took you away.”

Robert Schwarz, a lawyer who represents Chavez Larin, 26, argued his client was implicated by lying witnesses who have admitted killing Hernandez themselves.

The lawyer described his bald, round-faced client as a wannabe gangster who sucked up to gang leaders but lacked the nerve to kill.

“He didn’t go up that mountain to kill Elvin Hernandez because that’s not who he is,” Schwarz said. “He’s the ultimate poser.”

The gang struck again six months after Hernandez’s death, when Brayan Andino slipped out of Panorama High School with a girl.

Andino, 16, had left Honduras four years earlier to join his mother in the San Fernando Valley, according to evidence presented at a trial in 2020. He claimed to belong to 18th Street, MS-13’s most bitter rival, but a campus police officer testified it was only the foolish bluff of a 10th-grader who wanted to seem tough.

Andino’s best friend — the girl he cut class with — was in a relationship with a young MS-13 hanger-on. She testified she lured Andino to Balboa Park, where they were met by an MS-13 member who suggested they smoke marijuana in the mountains.

In Lopez Canyon above Sylmar, Andino was ambushed by six teenagers and young men. One was Roberto Corado Ortiz, the reputed leader of a small MS-13 clique called the Los Angeles Locos, Siddall said.

Corado told police he went to Lopez Canyon to “evaluate” a prospect, Bryan Rosales Arias. After they killed Andino with a garrote, baseball bat and serrated knife that Corado called “the gut ripper,” the clique leader looked disapprovingly on one of the killers who vomited during the drive home, Siddall said.

Andino’s remains were only found after a wildfire blew through Lopez Canyon, burning away the brush to reveal a charred skeleton.

Corado’s lawyer, Oliver Cleary, all but acknowledged his client had killed when he told the jury, “everything he did, he did to live.”

Corado, 30, grew up in El Salvador and joined MS-13 when he was 11, Cleary said. For Corado, the kill-or-be-killed rules of the gang were “all-encompassing,” his lawyer said.

Rosales’ attorney, Vitaly Sigal, said authorities had suborned lies from killers by dangling the prospect of freedom. He cited a transcript of a police interview in which an investigator told a prospective witness he needed to bring the “hungry prosecutor” a “plate of pupusas” before the witness would be allowed to eat a pupusa himself.

Sigal noted the two men who testified against his client had admitted 10 slayings between them. “So they join Team USA,” he argued, “and now everything they say is the absolute truth.”

Nine months after Andino was killed, Corado took another victim up to the mountains, Siddall argued.

With him was Roger Chavez, 19, who had emigrated from Honduras three years earlier, a relative told The Times. He struggled to fit in at Huntington Park High School and dropped out, hoping to learn his older brother’s trade as a diesel mechanic.

When a friend proposed they smoke marijuana with an ocean view the afternoon of July 21, 2018, Chavez agreed. He either wasn’t aware the friend was affiliated with MS-13 or he was wildly naive. Like Andino, Chavez claimed to be affiliated with the rival 18th Street gang.

In the mountains above Malibu, Chavez and his friend were met by Corado, Rosales’ brother Erick and another MS-13 member. Chavez took out his phone. In a Snapchat video shown in court, he flashed an 18th Street hand sign and panned over his companions, who turned their faces away. Corado would later tell the police that when Chavez took the video, he knew “we screwed this one up.”

But rather than calling off the hit, they waited until nightfall, smoking and drinking with Chavez, before Corado shot him in the back of the head, Siddall said. Corado then passed the gun around so everyone could shoot, the prosecutor argued.

Arrested for the homicide and held in a bugged jail cell, Erick Rosales told his cellmate — a police informant — that it “took some bulls—ing” to get Chavez to the mountains, but he “totally trusted us.”

Erick Rosales’ lawyer, Carlos Juarez, argued the jailhouse statement wasn’t reliable because his client, then 19, was physically intimidated by the larger, older informant who held himself out as a gang leader.

Asked by his cellmate what he felt after shooting the teenager, Erick Rosales said: “Like going to get high.”

Not all the killings took place in the mountains.

Osvaldo Hernandez, 22, had just returned from the gym the night of Dec. 6, 2018, when an MS-13 member spotted him near his family’s Van Nuys apartment, Siddall said.

Hernandez was hanging out with a friend in an alley covered in graffiti from warring gangs but he was not affiliated with any crew, Siddall said. His father told The Times he’d just opened his own business, Ozzie’s Mechanic Shop in Canoga Park, after saving up and learning to fix cars while working at a dealership.

Chavez Larin, the reputed leader of the Fulton clique, was driving around with some prospects when they spotted Hernandez, according to Siddall. The prosecutor said Chavez Larin handed a gun to Edwin Martinez and a juvenile. The two walked up to Hernandez and demanded, “Where you from?”

The last thing Hernandez said was, “Oh, f—.”

According to Siddall, Martinez killed twice more in the next five weeks.

Oscar Fuentes, a skinny 19-year-old member of MS-13, had broken two rules, Siddall said: He’d gotten strung out on methamphetamine and he was missing clique meetings.

On Jan. 13, 2019, Fuentes was spotted at Whitsett Park, the heart of the Fulton clique’s territory. Martinez sent a Facebook message to the juvenile with whom he’d allegedly killed Hernandez a month earlier.

“You have a little present here,” Martinez wrote.

After the juvenile didn’t respond, Martinez, Chavez and two others picked up Fuentes from the park and drove him to a remote area near Santa Clarita, Siddall said. Chavez handed a revolver to a prospect who shot Fuentes in the head, according to the prosecutor.

Fuentes’ remains were never located. Detectives found only a skull, unearthed, like Andino’s bones, after a wildfire, with a bullet hole through the forehead.

Martinez’s lawyer, Shaun Khojayan, argued it was possible that Fuentes simply disappeared and is still alive. The only proof that Martinez was involved in any killings was the word of cooperators whose accounts weren’t supported by physical evidence, Khojayan said.

A few hours after Fuentes was killed, Martinez returned to Whitsett Park with two others, Siddall said. Chavez Larin had ordered them in a Facebook message to “take out the trash.”

The three began waking up homeless people, demanding to see their tattoos, Siddall said. When they lifted up Bradley Hanaway’s shirt, they saw the San Fernando Valley area code, “818,” and the words “Forever Grateful,” the prosecutor said.

Mistaking the numbers and letters for a show of allegiance to 18th Street, they shot Hanaway to death, Siddall said.

“His major sin was he was sleeping in their park,” the prosecutor said. “Their park. As if they own it.”

The jury began deliberating Wednesday. If convicted, the defendants face life in prison.

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments