The hidden power of marathon Senate speeches: What history tells us about Cory Booker’s 25-hour oration

Published in News & Features

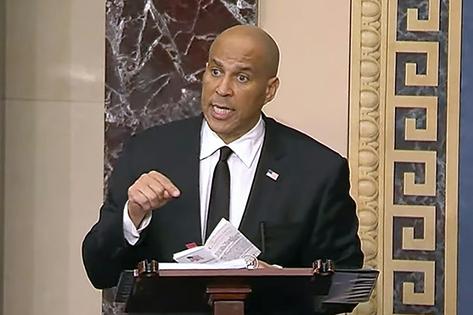

Democratic U.S. Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey made history on April 1, 2025, when he stood on the Senate floor and spoke for 25 hours and five minutes, delivering the longest floor speech in the history of the U.S. Senate.

Booker’s speech detailed his concerns about President Donald Trump’s new executive orders, other policies and approach to government in his second term.

“I rise tonight because silence at this moment of national crisis would be a betrayal of some of the greatest heroes of our nation. Because at stake in this moment is nothing less than everything that we brag about, that we talk about, that makes us special,” Booker said.

Although Booker’s speech was not technically a filibuster, meaning a prolonged action at the Senate in order to delay or stop a vote on a legislative action, it was clearly a monumental physical achievement. Booker stood, wearing a black suit, for the entirety of his speech and did not pause to take bathroom or meal breaks.

What does the subject matter of Booker’s speech, as well as his style of giving it, say about its potential effectiveness? Could it succeed where filibusters have failed?

Many other long Senate speeches in history offer a variety of useful historical hints about the political significance of Booker’s record-breaking speech.

One unusual element of Booker’s oration is that it was not focused on just one narrow issue.

Most of the lengthiest filibusters from across Senate history are focused on bills that cover important but specific issues. In 1953, Sen. Wayne Morse of Oregon, for example, set a record for the longest filibuster when he spoke for 22 hours and 26 minutes. Morse protested a bill involving the transfer of land and oil rights between coastal states and the federal government. The bill passed, despite Morse’s filibuster.

Sen. Strom Thurmond, the South Carolina politician who broke Morse’s record just four years later, infamously – and unsuccessfully – protested the Civil Rights Act of 1957 with a 24-hour, 18-minute speech.

Booker’s speech came in the midst of a vote to confirm Matthew Whitaker as the U.S. ambassador to NATO. Whitaker was confirmed shortly after Booker’s speech concluded.

Booker and the procession of Senate colleagues who asked him questions referenced this and other appointments in their remarks. But Booker largely used the speech to build a much bigger case against the Trump administration, most notably that the administration had wrested from Congress much of its constitutionally mandated budgetary authority by extensively cutting federal staff, grants and spending without congressional approval.

“These are not normal times in America,” Booker said toward the beginning of his address, “and they should not be treated as such in the United States Senate.”

The rules and culture of the Senate have always been more lax when it comes to what congressional experts call “germaneness” – in other words, how relevant a Senator’s action is to whatever is being debated.

For example, the Senate often allows nongermane amendments, meaning those that have little or nothing to do with the bill being debated. Booker leveraged that Senate tradition to make a larger point about what he called an ongoing “crisis” in American democracy.

Booker may have covered a wide variety of areas in his speech, ranging from proposed Republican cuts to Medicaid to mass firings of federal workers, but there’s no question that he stayed focused on his critique of the Trump administration – a difficult task to stick to for 25 straight hours.

Booker’s predecessors in the pursuit of Thurmond’s record have demonstrated this difficulty in keeping a marathon speech focused.

For example, Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas diverted from his argument when he gave a 21-hour, 19-minute speech protesting President Obama’s signature piece of legislation, the Affordable Care Act, in 2013.

Cruz, who still serves with Booker in the Senate, took the opportunity to tell his young daughters a bedtime story on the Senate floor, reading aloud from Dr. Seuss’ children’s book “Green Eggs and Ham.”

Louisiana Sen. Huey Long, meanwhile, shared recipes for southern fried oysters during his 1937 protest of the federal appointments process.

Booker, on the other hand, almost uniformly kept his focus on his grievances against the Trump administration and used only notes designed to reinforce his central argument that Trump is not leading in the best interest of the country.

According to an April 1 press release from Booker’s office, the senator drew from over 1,000 pages of prepared material assembled by his Senate aides, including stories from more than 200 Americans who had written to Booker protesting Trump’s actions.

In many instances, Booker also spoke extemporaneously about the administration’s actions. At other times, his fellow senators broke in for a lengthy question, but even these kept the conversation, and Booker’s attention, focused on taking Trump — and occasionally Elon Musk – to task.

In all instances, Booker used his speech to rally the public.

“My voice is inadequate. My efforts today are inadequate to stop what they are trying to do,” he said at one point. “But we the people are powerful, and we are strong.”

Of course, with few tangible results to show for lengthy Senate speeches, people might be tempted to view these long orations as little more than trivia or political theater.

On some occasions, filibusters have made a legislative impact. Sen. Alfonse D'Amato of New York, for example, filibustered a budget bill in 1986 for nearly 23½ hours to protest an amendment that would have killed funding for a jet trainer plane manufactured in his state. His filibuster didn’t stop the bill entirely, but he did secure a concession that prolonged the project’s life.

For the most part, however, lengthy filibusters throughout history have been largely fruitless efforts legislatively. Even so, the symbolism of these speeches, including Booker’s, can have effects on politics and representation that last beyond the legislation the senator is protesting.

It’s difficult to know yet just how effective Booker’s efforts will be in motivating an anti-Trump coalition to stand up to the administration, either in Congress or among voters.

But politically speaking, Booker’s timing was fortuitous – on April 2, the same evening Booker wrapped up his address, liberals secured a crucial Wisconsin Supreme Court seat in a high-turnout election, when Judge Susan Crawford beat Judge Brad Schimel. Schimel is a Trump supporter and received nearly US$20 million in donations from organizations supported by Musk.

Democratic politicians also outperformed expectations in two special elections to the U.S. House in Florida, though they lost the races.

Taken together with Booker’s herculean effort, these events could serve as a catalyst for Trump’s opponents to strike back in the coming months.

The symbolic significance of Booker’s achievement has also not gone unnoticed. Booker, who is Black and reflected on ancestors who were both enslaved or enslavers in his speech, was himself mindful of the historical relevance.

“To be candid, Strom Thurmond’s record always just really irked me,” Booker said after his speech in an interview with MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow.

“The longest speech on our great Senate floor was someone who was trying to stop people like me from being in the Senate.”

If nothing else, Booker took that record from Thurmond and made it his own.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Charlie Hunt, Boise State University

Read more:

How Democrats are making a mistake in rural America – by not showing up

US Senator Cory Booker just spoke for 25 hours in Congress. What was he trying to achieve?

GOP lawmakers eye SNAP cuts, which would scale back benefits that help low-income people buy food at a time of high food prices

Charlie Hunt does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments