WA businesses caught between high costs, tariffs -- and weary consumers

Published in Business News

SEATTLE — In the face of stubborn inflation and higher costs from new tariffs, many businesses in Seattle and across Washington face a tough choice:

Eat those rising costs or pass them along.

At The Masonry, which offers wood-fired pizza and craft beer near Seattle Center, co-owner Sam Morin has been closely watching the “creeping” price increases for the meats used in their popular meatballs.

Morin said The Masonry is already a lean operation, with little room for extra costs. It has been a long time since the menu price was increased, and I really don't want to ... raise it any more," she said. "But at some point, it’s going to have to happen.”

It’s an increasingly common refrain these days as businesses navigate rising costs, a trade war and economic uncertainty.

In July, U.S. wholesale prices rose 0.9% from June and jumped by a larger-than-expected 3.3% from July 2024, the largest yearly increase since February, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Producer Price Index report.

That rise suggests many U.S. producers “are either passing on higher costs or seeing the opportunity to increase profit margins,” said Brian Kelly, a Seattle University associate economics professor who studies trade policy.

Some wholesale prices have dropped. Gasoline and jet fuel, for example, were 14% and 13% cheaper, respectively, in July than a year ago, federal data shows.

But generally wholesale prices have trended higher — and sometimes by a lot.

Wholesale prices for fresh and dry vegetables were up 16% in July, compared with the same month a year ago. Roasted coffee and eggs were up 29% and 36%, respectively.

Other, less consumer-facing commodities also got costlier. Softwood lumber was up nearly 8%. Industrial gases increased 13% and nitrogen fertilizers are up 16%.

Some of those increases reflect ongoing inflation that picked up steam during the pandemic.

Construction costs, for example, have been on the rise for years, especially in the booming Seattle area. Wages, too, have been rising, climbing nearly 7% in Washington in 2024, according to state figures.

But the recent wholesale price surge also reflects tariffs, or import taxes, that the Trump administration has imposed on goods from China, Canada, Mexico, the European Union and other countries, starting in February.

At Merlino Foods, a Seattle-area food service distributor, the olive oil and cheeses imported from Europe “are all getting hit pretty hard” by “the whole tariff circus," said co-owner Todd Biesold.

Keeping tariffs at bay

As elsewhere, many businesses in Washington spent much of the year trying to soften the blow from tariffs and other inflationary factors.

For some companies, including Jet City Device Repair, that meant putting in extra large orders for spare parts several months ago, before the expected tariffs kicked in, said Siawash Popal, general manager.

Those shipments helped Jet City, a smartphone and tablet repair service in Seattle and Bellevue, avoid price increases. But they also required the small company to manage a lot of extra inventory and “tied up all of our cash,” Popal said. “That was a very stressful time.”

Many companies made similar bets. Starting last summer, imports jumped at many U.S. ports on expectations that then-candidate Trump might win the November election and begin implementing the higher tariffs he had campaigned on.

That "forward buying" continued through April, according to data from the ports of Tacoma and Seattle, which handled nearly 430,000 inbound containers in the first four months of 2025, a 22% increase from the same period in 2024.

That surge reversed in May, June and July, when container imports fell 20% compared with the same period last year.

Other companies tried to reduce their reliance on foreign goods by shifting to domestic suppliers.

Some construction firms, for example, have been able to find domestic supplies of building materials that are either manufactured in the U.S. or were purchased by wholesalers before tariffs kicked in.

In many cases, domestic suppliers "still have product that hasn't been hit by tariffs yet," said Nathan Jenkins, Seattle-area director of business development at Mortenson, a national construction firm with many large local projects, including the Climate Pledge Arena and North Tower at the Providence Swedish First Hill campus.

That extra supply is likely one reason overall construction costs haven’t risen quite as fast as some experts initially feared when the Trump administration began rolling out tariffs in February.

In the Seattle area, construction costs rose 2.4% in the second quarter of 2025 compared to the first quarter, and by 5.9% over the second quarter in 2024, according to a widely used cost index produced by Mortenson.

That’s a painful jump, but it’s substantially smaller than what Seattle builders saw early in the pandemic, when construction costs were rising by double digits.

Another bit of good news: Those stockpiled supplies are holding up. "We're just starting to see people working through the inventories in their warehouses," Jenkins said.

The less good news: One reason domestic inventories have remained so strong is that "construction starts have slowed down," said Jenkins, with Mortenson. "Demand has slowed down a little bit."

Something's got to give

Still, tariff workarounds have limits.

For some wholesale products, there simply isn’t enough domestic production to replace imports from places such as China, which already faces tariffs and could see more if the countries' leaders can't settle their disputes.

Many of the chemicals used on commercial farms are made from imported ingredients, “and probably 90% of those come out of China,” said Leslie Druffel, outreach director at McGregor Company, a Colfax, Whitman County-based company that supplies farmers.

Another limit: Many domestic suppliers have used tariffs as an opportunity to raise their prices, said Seattle University’s Kelly.

He pointed to imported steel, which initially saw a 25% tariff in February and now is tariffed at 50%. During that same period, prices for some domestic steel products have risen by 20%, Kelly said.

“Nothing evil about it,” Kelly said, of the domestic increases. “It’s just the market at work.”

And, of course, tariffs explain only a fraction of overall inflation.

Many companies spend more on labor than on raw materials, and in Washington, the average wage rose to $95,160 in 2024, a nearly 7% increase over 2023, according to the state Employment Security Department. By comparison, the average wage grew by 5.9% in 2023.

The broader limit, however, is companies can't keep eating cost increases, whether from tariffs or other factors.

“There’s only so much a company like ours can absorb before we have to start passing that on to our customers,” said McGregor’s Druffel.

That calculation can be especially difficult for smaller companies, said Kelly, with Seattle university.

Many are already facing thin profit margins and have little capacity to absorb a higher cost. Yet to raise prices is to risk losing customers, who may gravitate to other sellers or find cheaper options.

Or in the case of discretionary goods and services, such as gifts and dining out, consumers may simply do without, especially given broader concerns about the economy.

"The anecdotal evidence is that consumers are cutting back on some types of expenditures because they're concerned about the future," Kelly said.

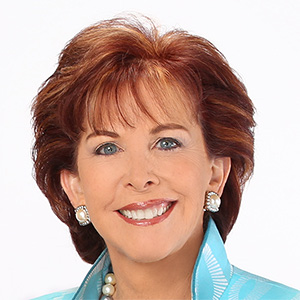

That's all front of mind for Kelsey Lewin, co-owner of Pink Gorilla Games, a gaming and collectibles retailer with three stores in Seattle and a new location in Las Vegas.

On Aug. 29, the Trump administration is ending the so-called de minimis exemption that has allowed U.S. companies to avoid paying import taxes on imports valued at less than $800.

Lewin said that will mean paying 15% more for many of her products.

Lewin said she can absorb some of that cost increase. But on certain products, such as boxes of popular Pokémon trading cards, her margins are already so small that “if we ate that cost, we would be making negative money.”

Lewin isn't worried about her business, but she's bothered by the need to raise prices, even modestly, at time when everyone is already so anxious.

"It just means that everyone else is paying a little bit more for everything," she said. "And those things add up.

©2025 The Seattle Times. Visit seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments