Last Max stored at Boeing 'shadow factory' after crashes, pandemic departs

Published in Business News

After six years of work, Boeing has flown the final in-storage 737 Max out of Moses Lake, Washington, marking the end of a grueling chapter in the company’s history.

Boeing began storing Max planes at Moses Lake, as well as other facilities in the region, in San Antonio and in Victorville, California, in 2019, after two fatal Max crashes led the Federal Aviation Administration to ground the plane. The FAA’s mandate lasted 20 months, eventually prompting Boeing to halt production of its most popular plane.

But, optimistic that the Max would return to the skies quickly, Boeing mechanics continued building the plane in the company’s Renton factory for 10 months before the production halt, leaving Boeing with hundreds of planes in storage.

Boeing's Max storage inventory grew in 2020, when the COVID pandemic upended air travel and airlines canceled deliveries amid the financial crunch.

In what Boeing called “shadow factories,” mechanics maintained the engines and other systems on the parked planes, ensuring everything continued to work correctly. For some planes, mechanics installed a new software package to fix the Max’s flawed flight-control system. That software — the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System — was implicated in the two fatal plane crashes in 2018 and 2019, which killed 346 people.

Boeing has spent the last six years maintaining and reworking that stash of planes, which reached 450, including 250 stored at Moses Lake. This month, Boeing finished working its way through that inventory.

It flew the final stored 737 Max from Moses Lake to Seattle, according to an internal company announcement viewed by The Seattle Times. Boeing had already worked through the remaining stored planes at its other facilities.

With the Moses Lake flight, all the stored Maxes “have been reactivated for delivery,” Boeing wrote, “marking the ‘beginning of the end’ for 737 Max storage operations.”

The final stored plane's departure was first reported Monday by trade publication Flight Global. The plane will get a fresh coat of paint before delivery to Air China later this year, according to Flight Global.

For Boeing, the maintenance and rework has been a financial drain and slowed its production of new planes.

Each parked plane took cash out of Boeing’s pocket, as it couldn’t collect on the final delivery to airline customers, and took workforce and equipment away from its other production lines.

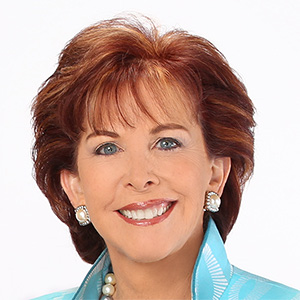

Joseph Phillips, an economics professor at Seattle University, called the shadow factory a “distraction” that was pulling Boeing's resources away from “the core of what they want to do … build planes and put them out the door.”

Now, they don’t have to use those resources that way,” Phillips said. “They can turn around and use them for something much more productive.”

Just as Boeing's Max inventory grew, the company similarly had to devote time and resources to a shadow factory in Everett, designed for reworking the company’s widebody 787 Dreamliner. There, mechanics repaired small gaps at the fuselage joins of 122 planes. Boeing closed that shadow factory in February after five years of operation.

Now, with the end of the Dreamliner rework and the stored Maxes, Boeing expects to see improved profit margins, because “you don’t have these two very expensive shadow factories up and running anymore,” then-Chief Financial Officer Brian West told analysts earlier this year.

Boeing has been expecting to reach this milestone this year, though its timeline was slightly pushed back after a Machinists strike in the fall halted production at Boeing’s Puget Sound-area factories for two months.

West told analysts at the most recent earnings call in July that Boeing would finish reworking the stored Max planes in the third quarter, which runs from July to September.

Boeing ended the second quarter with 20 737 Max 8 planes in storage, West said on the call. All those are slated for customers in China, he added.

Boeing declined to comment on the final Max rework this month, pointing instead to West’s recent remarks, and declined to share how many employees are based in Moses Lake.

At its “peak,” there were nearly 1,000 people working on more than 250 stored Max planes in Moses Lake, Boeing wrote in its internal company announcement.

The company has already shifted some workers from Moses Lake to Renton, to join the production lines for new Max planes, but the work won’t stop in Eastern Washington.

Employees there “will now turn to other projects,” Boeing wrote in its internal post, including maintaining its inventory of 737 Max 7s and 10s, two variants that are awaiting certification from the FAA.

Boeing has about 35 combined Max 7s and Max 10s in stock, West said in July.

©2025 The Seattle Times. Visit seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments