New database catalogs plant species in latest effort to restore prairies

Published in Business News

To the untrained eye, the restored prairie lands of Illinois look exactly how you would imagine they looked hundreds of years ago. But many plant species are still missing, and recent efforts — including a newly launched database — aim to ensure that the prairies are restored much more comprehensively.

Jack Zinnen, a researcher with the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign’s Illinois Natural History Survey, said that he realized there may be a gap in prairie knowledge during a conversation he had with a colleague who studies similar grasslands in Australia.

“I love prairies, and I was bragging about how diverse they are, because there are these incredibly rich and interesting visual ecosystems,” Zinnen said. “And he’s like, Oh, great. How many species are in a prairie? And I go, ‘… a lot?’”

Zinnen dug a little deeper, and in doing so he found out that while lists of species in many individual prairie remnants had been collected for decades, there was no one place where they had all been put together. This meant that there was no way of easily comparing all prairies across the Midwest. It also meant that many of the commercial seed mixes used to restore prairies were incomplete.

Zinnen was part of a team that recently launched the RELIX database, alongside Jeffrey Matthews, associate professor in natural resources and environmental sciences at the U. of I. RELIX catalogues every plant species in 353 prairie remnants — parts of the native grasslands of the Midwest that were not converted to farmland during colonization.

“A good way to think about prairie remnants is, they were spared by accident,” Zinnen said. “These were places that you really couldn’t farm or were not worth farming, and many of them had these kind of lucky conditions to keep them as a prairie community and not be turned into woodland or some type of non-native ecosystem.”

Andrea Kramer, senior director of restoration at the Chicago Botanic Garden, said that in Illinois less than 1/10th of 1% of prairie habitat remains — that’s a loss of 99.9% of native tallgrass prairie. These prairie remnants, as they’re called, are often described as “postage stamps” on the map, just a few acres each.

Almost all of pre-colonial Illinois was tallgrass prairie, which is characterized by grasses growing up to 8 feet tall with deep-running roots. These deep root systems are part of why these plants survived the frequent wildfires characteristic of a prairie environment as well as prolonged droughts — until the advent of the steel plow, which could tear through these deep root systems better than any tools before it.

Environmentalists like Kramer focus on prairie restoration for a variety of reasons. For one, the deep-running root systems of prairies both help keep carbon out of the atmosphere and hold soil in place to prevent erosion.

But another reason is that, because of the sheer number of plant, insect, and animal species that live in them, prairies are incredibly resilient. If prairies are restored to their original level of species diversity, they will have a better chance of withstanding natural challenges.

Kramer brings up the recent case of the emerald ash borer, a small beetle from Asia that arrived in North America around 2002. While the beetle doesn’t cause problems in its native habitat, it wreaks havoc on American ash trees, its larvae boring deep into the trees to feed and killing millions each year. This has been a particular issue in suburban areas where ash trees are the only shade trees being planted. American ash trees are now dying en masse from the emerald ash borer’s feeding, and no trees remain in those areas. Had those areas used more than one type of tree, they may not be suffering the effects of the ash borer so severely.

“The more species we have, the more resilient it will be to things like drought or flood or the next pest or pathogen that either naturally comes or is accidentally introduced that we just can’t prepare for,” Kramer said.

To create the database, the team gathered information on the species in those 353 prairie remnants from a variety of sources: academic publications going as far back as 1950, books such as the 2001 Prairie Director of North America, databases from unpublished studies, and surveys conducted by prairie land managers they contacted.

Zinnen acknowledges that the database is “far from comprehensive” in a note that accompanies the database when it’s downloaded. The work had to stop somewhere, he said, and after almost three years of research, the team decided that the data was ready to be released.

RELIX also pairs the species data with the locations and subtypes of prairie where each species was found. Matthews said that this is particularly important for the database’s users. “For example, if a practitioner wanted to restore a prairie on sandy soil in southern Wisconsin, they might start by generating a list of plant species found in sand prairies in southern Wisconsin and northern Illinois. They could use the database to generate a list of potential species for seeding, then seek out native seed vendors that supply those species.”

Right now, RELIX is being used primarily in seed-based restoration projects — that’s when an area that was formerly used for farming, industry or other efforts is restored to its original prairie state through using seeds once the land is cleared.

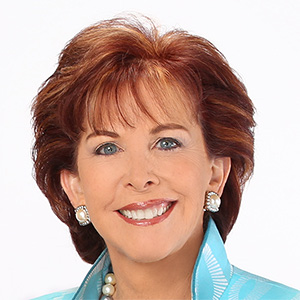

“We want our restorations to trend toward the species abundance and composition that is as similar to a remnant reference as possible,” said Pati Vitt, director of natural resources at Lake County Forest Preserves and one of the leaders of the Chicago Wilderness Alliance’s “Managing Healthy Landscapes” initiative.

Vitt manages 31,000 acres of prairie land in Lake County. She says that the RELIX database is particularly relevant to seed-based restoration. It’s widely known within the prairie restoration community that available seed mixes aren’t quite accurate to the actual composition of prairie remnants; this database allows researchers to prove that, and see exactly where the seed mixes are falling short.

In December, the RELIX team published a study comparing the blooming times of flowering plants in prairie remnants to those sold in prairie seed mixes often used in restoration. What they found was that these mixes tend to prioritize summer-blooming flowers at the expense of spring-blooming flowers, which means that insects emerging from hibernation in spring are unsupported.

Zinnen likens the current state of prairie restoration seed mixes to fast food — it’s far better than nothing, but it doesn’t quite include all of the benefits of a well-balanced meal. “It fulfills a function, it’s standardized, it’s efficient,” he said, “I like fast food, I eat fast food, but in terms of capturing what could be done, it is really only a small subset.”

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments