Trump can try to fire Lisa Cook. He won't win

Published in Business News

President Donald Trump won’t win his tussle with Lisa Cook, the Fed governor he tried to fire Monday night. But I’m not sure winning is the point. More likely, this is just one more battle in the president’s war of attrition against the Federal Reserve and its Federal Open Market Committee.

Trump’s letter of dismissal rests on the criminal referral by the director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency, alleging that Cook made misstatements on one or more mortgage applications. Therefore, the president writes, he can fire her for “cause” (the language of the applicable federal statute).

This interpretation is plainly wrong, and I’d expect a federal district judge to issue an injunction any hour now — one the US Supreme Court is bound to uphold. But before we get to why Cook will prevail (her lawyer said she intends to sue), let me note the small ray of hope in this otherwise outrageous assault.

Here’s the small yet significant good point: Trump seems to have accepted that he can’t fire a governor of the Federal Reserve except for cause. Back in June, when the White House effort to dismiss Fed Chair Jerome Powell seemed to be imminent, the Supreme Court fired a shot across Trump’s bow. In a brief order that essentially upheld the president’s authority to dismiss members of the National Labor Relations Board, the justices went out of their way to warn that the Fed is different. As “a uniquely structured, quasi-private entity that follows in the distinct historical tradition of the First and Second Banks of the United States,” the Federal Reserve was deemed distinct from other agencies whose heads the courts have allowed recent presidents to cashier. By setting forth alleged “sufficient cause” to fire Cook, Trump may be signaling his acquiescence.

That’s the end of light ray. The rest is grim.

So, let’s state what should be obvious: The criminal referral on which the effort to dismiss Cook rests doesn’t constitute sufficient cause.

Don’t get me wrong — a criminal referral is no trivial matter. Were we in a law school classroom, we could easily construct an argument for the proposition that the mere existence of the referral is more than sufficient cause for dismissal of an otherwise protected official.

But we’re not in that world. For one thing, a referral is not a criminal charge. It’s not an indictment or a warrant. It represents no more than a suspicion of wrongdoing. There’s no requirement of probable cause or even investigation. I don’t imagine that Trump considers himself somehow less qualified for office as a result of the 2022 criminal referrals about his own conduct, sent to the Justice Department by the Jan. 6 committee. And he’s right. A criminal referral isn’t a legal document. It’s only a suggestion that particular conduct might be worth looking into.

Most criminal referrals lead nowhere.

Moreover, precisely because criminal referrals have no legal significance, they can be easily concocted. In the era of lawfare, it’s not hard to imagine a highly partisan agency head searching determinedly through the records for any allegation that can be made against someone the president wants to be rid of. After all, every one of us likely has committed a federal crime.

I’m not saying the allegations against Cook are without foundation — I’m not in any position to know. What I am saying is that, precisely because of the strong temptation to play politics with criminal referrals, the mere existence of one does not remotely create a valid basis on which to rest a “for cause” dismissal.

Which is why Cook will win.

But even if a criminal referral isn’t evidence of wrongdoing, it can prove expensive — for the target. And I wonder whether that isn’t the point. There’s an episode of The West Wing where the president is under investigation by a special prosecutor. The White House counsel advises a relatively junior aide who’s been subpoenaed to hire a lawyer. The aide asks how much that will cost. The answer: “Assuming you saw nothing wrong, heard nothing wrong and did nothing wrong — about $100,000.”

That was in 2001. Goodness knows what the going rate is now.

So even if, as seems likely, nothing comes of the criminal referral against Lisa Cook, she’s likely to face hefty legal bills. On a government salary, that can be a crippling expense. The administration, on the other hand, has more than 40,000 lawyers to sic on its opponents without cost. That’s why, even if — as is almost certain — the courts strike down the effort to dismiss Cook, the message to other government officials who might resist Trump’s whims is that defiance could prove costly.

Which is why the attempted firing of Cook makes clear that Secretary of the Treasury Scott Bessent was wrong — optimistic, perhaps, but still wrong — when, earlier this year, he likened his boss’s verbal attacks on the Federal Reserve to a basketball coach “working the refs” in the hope of getting better calls.

Trump isn’t just working the refs. He wants to replace them with new ones who’ll spot all the other side’s fouls and ignore his own. If he can’t fire the refs, he’ll settle for wearing them down. What he seems unprepared to do is to make sure that he and his team play by the rules.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

• Firing Lisa Cook Won’t Bring Down Interest Rates: The Editors

• The Conservative Constitutional Revolution Is Gaining Speed: Noah Feldman

•Federal Advisory Panels' Powers Just Got a Boost: Stephen L. Carter

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

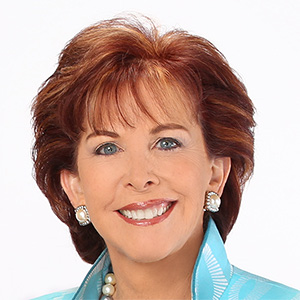

Stephen L. Carter is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist, a professor of law at Yale University and author of “Invisible: The Story of the Black Woman Lawyer Who Took Down America’s Most Powerful Mobster.”

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments