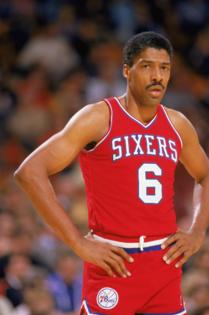

In 1980, Dr. J opened a dress shoe salon in Philly. It helped create a business blueprint for future athletes.

Published in Basketball

PHILADELPHIA — Julius Erving had a problem. It was not basketball-related. He was more than fine in that department. This was something different: the shoe department.

Erving wore size 16, and for most of his career, he had trouble finding dress shoes that fit him. So, he decided to be proactive. In September 1980, just before an MVP season with the 76ers, he opened a store, The Doctor’s Shoe Salon, on South 2nd Street in Society Hill.

The salon did not sell sneakers. Erving decided that it would only offer women’s and men’s fine leather shoes, sizes 8 and up.

“If you come in with a nice pair of shoes on, it generally grabs somebody’s attention,” the 75-year-old Erving said in late March. “If you come in with sneakers on, it grabs their attention in a different way.”

The Sixers star invited his teammates to the grand opening, as well as a few other players who preceded him: Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain, “big guys who had big feet.”

He gifted them shoes, and gave his teammates a 50% discount. A few of the bigger guys (with bigger feet) took Erving up on the offer, like centers Darryl Dawkins and Caldwell Jones.

Erving’s longtime friend, Alonzo Somerville, ran the store on a daily basis, while the Hall of Fame forward checked in a few times a week. It was a well-conceived idea, but the timing wasn’t right.

“Interest rates got up to like 23%,” Erving said. “It was like working for the bank.”

Nevertheless, the salon served as a training ground for his future business ventures. After it closed in 1982, Erving continued to take risks. In 1983, he and a group of investors bought a share of a Coca-Cola bottling plant in New York.

That same year, he and Larry Bird signed deals with Electronic Arts to create a video game — "One on One: Dr. J vs. Larry Bird" — that was based on the two facing off against each other.

Over the next four decades, Erving became involved in everything from horse racing to cable television to toothpaste, creating a blueprint for a generation of athlete-business people to come.

“I’m proud of the fact that I opened a lot of doors,” he said. “And had people call for consultation — ‘How do you get involved in this? How do you get involved in that?’

“I had people who led me in that capacity. They weren’t necessarily athletes, but they were business people. So, it didn’t happen overnight. It wasn’t magic. You just have to keep a balance. You have to create balance in your approach.”

Developing an entrepreneurial spirit

Erving was never going to be one-dimensional. Not with a mother like Callie Mae Lindsey.

Lindsey grew up in South Carolina, where she studied education, and moved to Chicago in 1944. She was told her credentials weren’t good enough to teach, so she began to do domestic work.

When the family relocated to New York in 1946, Lindsey applied for some teaching jobs but ran into the same problem that she did in Chicago. So, she decided to do something completely different, opening a hair salon in Hempstead, Long Island.

The single mother of three ran her own business. She quickly built a following, with young girls all over the neighborhood venturing to her salon to get their hair styled.

“She was an entrepreneur,” Erving said. “She parlayed that into a pretty good business. I don’t remember the name of the salon. But I do know how to get there from our [old] apartment.”

Erving developed an entrepreneurial spirit, too. When he wasn’t playing basketball at playgrounds in Hempstead, he was working odd jobs, at a bicycle repair shop, a jewelry store and a local bakery.

By the time he was a teenager and getting recruited by colleges, the idea of studying business was on his mind. It was one reason he decided to go to the University of Massachusetts, as opposed to some of the bigger-name schools that recruited him.

UMass coach Jack Leaman had a good relationship with Erving’s high school coach, Ray Wilson, which certainly factored in. But Erving also liked the fact that the university had a strong business program.

“College is where [my interest in business] started,” he said. “I went to UMass, and I was pretty much a business major. I actually graduated from the school of Ed, because I left after my junior year and went to a program called University Without Walls, and was able to get my bachelor’s degree from the School of Education, not business, but I was always interested in business.

“And I always knew that there was going to be a path for me [there], especially if sports didn’t work out.”

Of course, it did work out. Erving was a dynamic athlete, with long arms and big hands. It seemed like he could do just about anything.

He was best known for his emphatic dunks and elegant finger rolls, but he could also defend and rebound and shoot; a multidimensional game for a multidimensional man.

“People talk about all the amazing dunks, but he had the body to do it,” said Erving’s former Sixers teammate, Henry Bibby. “There weren’t too many athletes that were [6-7], who could run and jump like that. And his hands were so big that he could cradle the ball and just move it in different directions. You never knew what he was going to do with it.

“So, it gave him an advantage to be more creative than the average person. His mind was always like that. That’s why he was such a good basketball player, because he was creative on the court, just like he was off the court.”

Erving began his career in 1971 with the ABA’s Virginia Squires. The three-time ABA MVP was traded to the New York Nets in 1973, and his rights were sold to the Sixers in 1976. He stayed in Philadelphia for 11 years, retiring after the 1986-87 season.

But throughout it all, even with the 16 All-Star Games and 37 playoff appearances, he always made time for his second love.

“Me and my teammates sat and had conversations [about business],” Erving said. “I used to have roundtable discussions, during my New York years, with Reggie Jackson and Arthur Ashe. Around 1973 or 1974.

“We’d go to my home, or their home, and we’d just talk about things outside of our sport. What do you do with money? What responsibility do you want to have in the community? If you can inspire others, it’s a good thing, not a bad thing.”

Mentoring the next generation

Erving’s retirement from the NBA didn’t leave him unfulfilled. He had other challenges and goals to pursue, most of them in the business world. He also found a new generation of young athlete businessmen to mentor.

There were longtime Bucks point guard Quinn Buckner and Pistons forward Terry Tyler, as well as Hall of Famer Magic Johnson, who consulted Erving while he was still playing about whether he should leave Michigan State early to go into the NBA.

Michael Jordan, whose line of sportswear changed the future of the sneaker and sports marketing industries forever, also studied the Sixers legend.

“Dr. J was one of the guys that I idolized from the business side of things, and I wanted to take that same passage and show that I was more than just a basketball player,” Jordan told The Ringer’s Jackie MacMullan in 2022. “I had a personality, and I had a business mindset. I can coordinate, and I can cross all different types of color barriers.”

It’s now common to see athletes expanding their reach beyond sports. Eagles cornerback Cooper DeJean is the face of Cooper Cheese. Phillies star Bryce Harper has an ownership stake in a high-end barbershop. Eagles center Cam Jurgens launched a beef jerky company when he was a senior at Nebraska.

But one of the first examples was a high-end store on South 2nd Street that sold dress shoes — not sneakers.

____

©2025 The Philadelphia Inquirer. Visit inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments