Supreme Court to hear oral arguments on Rebecca Slaughter firing

Published in Political News

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court is set to hear arguments Monday over President Donald Trump’s decision to fire Federal Trade Commissioner Rebecca Slaughter, in a case that could expand the control a president has over the executive branch.

Directly, the Trump administration asked justices to overturn a decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit reinstating Slaughter because a long-standing law prevents removals without cause from the FTC and several other key federal agencies.

However, experts and the parties said the outcome could decide broader issues of the balance of powers between a president running the government and a Congress seeking to shield some federal officials from political interference.

Lauren Miller Karalunas, counsel for the democracy program at the Brennan Center for Justice, said the Supreme Court effectively will be weighing whether the president can change the law after the fact.

“They won’t just be deciding the technical question of whether President Trump can remove these officials, they’ll also be deciding a much more profound question of whether the president can override the will of Congress,” Miller Karalunas said.

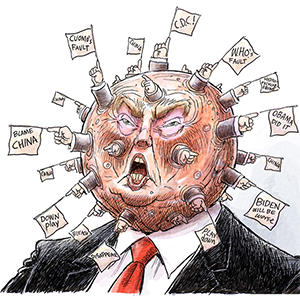

The case comes after Trump purged dozens of independent watchdogs and federal board members despite congressional protections against their removal this year.

The Trump administration is challenging a 90-year-old Supreme Court precedent known as Humphrey’s Executor, in which the Supreme Court upheld a law preventing the president from firing members of the Federal Trade Commission and similar agencies that perform “quasi-legislative” or “quasi-judicial” functions.

Trump fired Slaughter in March along with fellow FTC Commissioner Alvaro Bedoya. The pair challenged their firing in federal court, and Bedoya eventually dropped his case. Later, the D.C. Circuit eventually ruled in Slaughter’s favor and ordered that she be reinstated. The Supreme Court put that ruling on hold, over the objections of the court’s liberal justices.

The laws creating the FTC, the Federal Reserve Board, National Labor Relations Board, Merit System Protection Board and others include protections for the members of those boards.

Those agencies regulate “innumerable aspects of modern life,” the Justice Department told the Supreme Court in a filing, from nuclear waste to telemarketing and union disputes, and the president should be able to fire the officials who wield that power.

The Trump administration argued that the FTC and other agencies previously covered by that decision have executive functions, including issuing rules, adjudicating cases and investigating violations of the law, that should be considered executive powers rather than “quasi-judicial” or “quasi-legislative” ones.

“Congress and the courts cannot divert accountability ‘somewhere else’ by empowering unelected agency heads to wield executive power walled off from presidential control and electoral accountability,” the Trump administration argued.

The DOJ also argued that even if Congress could pass a law restricting Trump’s ability to fire officials, the courts could not intervene to reinstate them.

On the other side, Slaughter and her defenders argued that Congress intended for decisions to be made by agency officials whom the president would have a role in naming but would not directly control. Trump and the other defendants are now trying to change the law enacted by the legislative branch of government to suit their political whims, Slaughter’s lawyers contend in a brief.

“They seek to vindicate the principle of democratic political accountability by asking unelected and politically unaccountable courts to jettison longstanding laws enacted by the people’s elected representatives,” Slaughter’s brief stated.

Noah Rosenblum, a law professor at New York University, said that when the justices decide the case, they stand between allowing firing protections for senior agency officials they’ve been hostile to for years and a decision that could imperil the work of everyday federal employees and the independence of the Federal Reserve.

Rosenblum said he vacillates between feeling the case will not change much and a fear that afterward “all that Congress can do is pass laws, all that the courts can do is adjudicate cases, and everything else would be under the personal control of the president because of this ‘Schoolhouse Rock’ vision of American government.”

Rosenblum filed an amicus brief in the case, arguing that there is a long history of Congress creating federal officials who could not be removed by the president.

At the core of the case is Trump’s ability to control who leads so-called “independent” agencies such as the FTC.

Miller Karalunas and others, including more than 200 Democrats in Congress who filed a brief in the case, argued that a decision in Trump’s favor would effectively change the deals that previous Congresses made with previous presidents when they spun up the agencies at issue.

“With a decision that allows the president to ignore the checks and balances intended by Congress, the president can act as a kind of mob boss-like figure using agencies to harm enemies and benefit allies,” Miller Karalunas said.

The members of Congress, in their brief, argued that multi-member boards like the FTC represent a “long-standing compromise” between the presidency and legislative branch. Congress could create agencies that it deemed essential and they would be “insulated from the whims or short-term thinking of any given president.”

In recent years, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of allowing the president to remove numerous officials, including the head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and commissioner of the Social Security Administration, despite legal protections against their removal.

Oliver Dunford, a senior attorney at the Pacific Legal Foundation, said the Supreme Court’s recent merits decisions, as well as its emergency decisions in favor of the Trump administration, “pretty clearly suggests that the court believes the president should have the authority to remove the heads of multimember agencies such as the FTC.”

Of the dozens of officials removed by Trump this term, the conservative majority has let just two remain in their jobs while they challenge their firings: Federal Reserve Board member Lisa Cook and Register of Copyrights Shira Perlmutter.

The justices are set to decide the legality of Cook’s firing after oral arguments next year, and the justices paused the Trump administration’s emergency effort to remove Perlmutter, whose position sits within the Library of Congress, until after resolving both the Cook and Slaughter cases.

Justice Elena Kagan, dissenting from the justices’ decision to let Trump remove Slaughter while the case plays out, argued that the court shouldn’t have let the firing of Slaughter and other officials go through on an emergency basis.

“Our emergency docket should never be used, as it has been this year, to permit what our own precedent bars. Still more, it should not be used, as it also has been, to transfer government authority from Congress to the President, and thus to reshape the Nation’s separation of powers,” Kagan wrote.

Rosenblum said that depending on how the court decides the case, it could make huge changes in how American government works. Officials doing everyday work at other agencies could act only on signals from the White House, lest they fear losing their jobs, Rosenblum said.

“Do you want your patent application decided by a call from the White House? Do we want to live in a world where your IP rights are at the whim of the party in power? Presumably, the answer is no,” Rosenblum said.

Dunford said “the mistake” was made 90 years ago when the Supreme Court upheld the firing protections for members of the FTC. Since then, he said, members of Congress have been able to shove off hard decisions of government to growing federal agencies.

“Congress has ceded its policymaking power to these agencies, and members of Congress have been happy to let their egos go and stay in office by blaming these agencies,” Dunford said.

Sen. Eric Schmitt, R-Mo., and other members of the Senate Judiciary Committee echoed that argument in their own Supreme Court filing, stating that federal agencies cannot operate constitutionally without direct presidential control. Furthermore, it undermines government by “incentivizing Congress to pass the buck to faceless bureaucrats on difficult or intractable issues,” the brief stated.

©2025 CQ-Roll Call, Inc., All Rights Reserved. Visit cqrollcall.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments