Editorial: The US needs a strategy in Venezuela, not airstrikes

Published in Op Eds

With the deployment of the USS Gerald R. Ford, the world’s largest aircraft carrier, the U.S. has amassed a fearsome array of assets off the shores of Venezuela: dozens of advanced fighter jets, thousands of troops, guided-missile destroyers, special operations forces, armed drones, gunships, possibly a nuclear submarine. More useful, however, would be a strategy.

What purpose this armada is meant to serve remains stubbornly opaque. Strikes on speedboats allegedly running drugs in the Caribbean and eastern Pacific — which have killed more than 80 people since early September — hardly require such firepower.

The Pentagon has reportedly generated options to expand the campaign to targets in Venezuela itself, presumably in hopes of driving dictator Nicolas Maduro from power. At the same time, the president denied any such plans late last month, and White House officials seem unclear about the legal basis for an attack.

Many Americans would favor greater focus on the drug trade, which contributed to more than 80,000 deaths in the U.S. last year — 10 times as many as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan combined.

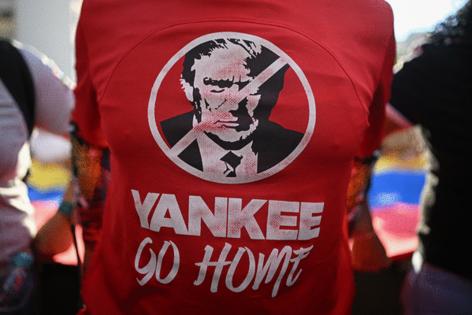

But the ad hoc nature of the administration’s campaign is arguably doing more harm than good. Focusing on the Caribbean ignores the main cause of U.S. overdoses: fentanyl smuggled from Mexico. Widely viewed as illegal, the boat strikes have reportedly led partners such as the UK and Colombia to cut off some intelligence sharing with the U.S. Maduro, by standing up to American bullying, may have bolstered his standing at home and in the region.

Meanwhile, the costs of this show of force are mounting. Operating a carrier strike group burns through millions of dollars a day. Each boat strike costs hundreds of thousands of dollars. Then there are the indirect trade-offs: With the Gerald Ford in Latin America, the U.S. currently has no carriers deployed in waters off Europe or the Middle East. Any land-based strikes would likely involve Tomahawk missiles, of which the U.S. has a limited supply.

The consequences of such an attack wouldn’t end there. Air and missile strikes are far from guaranteed to drive out Maduro or prompt a coup. Sending in the Marines could lead to a quagmire. Even if Maduro did step down or was captured by U.S. forces, there’s no guarantee any transition would be smooth. Political instability would create more space, not less, for cartels to expand.

The White House needs to decide what its goals are. If the hope is that gunboat diplomacy will encourage Maduro to resign peacefully, the administration should be ramping up talks to seek a credible handover of power. Airstrikes would be unwise, let alone an invasion. Yet the longer U.S. forces are engaged in pinprick attacks, the less intimidating they will be.

If, on the other hand, the administration really wants to stem the flow of drugs to the U.S., it ought to bring the right resources to bear. Rather than aircraft carriers and submarines, what’s needed are more Coast Guard cutters and Drug Enforcement Administration operatives. Rather than threatening Colombia and Mexico — the main sources of cocaine and fentanyl — the U.S. should be working with them to develop intelligence on cartels’ financial and logistics networks. If drones or special operations forces are required for specific missions, they should be employed with the full cooperation of host countries, not unilaterally.

The Pentagon’s most advanced assets should be focused on deterring a major conflict with a peer competitor such as China or Russia. The sooner they can return to that mission, the better.

_____

The Editorial Board publishes the views of the editors across a range of national and global affairs.

_____

©2025 Bloomberg News. Visit at bloomberg.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments