Noah Feldman: How constitutional limits become negotiable

Published in Op Eds

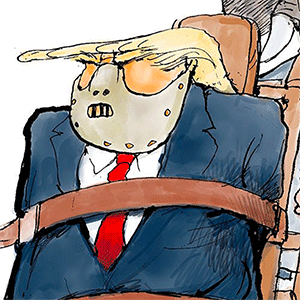

The most astonishing feature of Donald Trump’s decade as one of the most dominant figures in American politics is his ability to make the unthinkable seem not only thinkable, but possible. The president’s latest attempts to push the boundaries of what is conceivable — and legal — in our system of government include claims that his Justice Department “owes him a lot of money” for previous federal investigations and repeated suggestions that he might seek a third term — a move which would violate the 22nd Amendment.

Trump recently said he would not attempt to become president in 2028 by running as JD Vance’s vice president and then taking office after Vance resigned. “I think the people wouldn’t like that. It’s too cute. It wouldn’t be right,” he told reporters. Yet at the same time, he said, “I would love to do it.” Earlier this year, he said he was “not joking” about such a possibility.

By now, this pattern of political theater should seem familiar. First, Trump floats the idea of breaking some fundamental principle of politics — something so basic to eighth-grade civics and to our collective political imagination that it seems laughable. Then, supporters like Steve Bannon, who has been hinting about a semi-secret “plan” for Trump to become president again, start insisting that it is not only possible but inevitable. The rest of us — whether we are constitutional law professors (guilty), pundits (ditto), or simply committed citizens — start talking about the outrage.

In the most troubling part of this process, the outrage and ensuing debate themselves become a powerful normalizing force. After all, we debate constitutional and political questions all the time, in settings that range from the office watercooler to the Supreme Court. Those debates often mirror our partisan divisions, with liberals on one side and conservatives on the other.

As a result, the debate over what was once unthinkable begins to seem like an ordinary and legitimate political argument, one in which we are accustomed to each side winning occasionally, either through elections or in court. And therein lies the subtle danger: What we once considered unthinkable has gradually become part of our political imagination.

The way to stop this cycle is to show that specific unthinkable, unconstitutional ideas are unthinkable for good reason: They break the deep structure of our system, and their normalization would profoundly undermine the operation of the Constitution. If something as basic — and as clear — as the 22nd Amendment becomes negotiable, the entire legal order begins to unravel.

In other words, we need to maintain our common sense in the face of the question, “Why not?”

Let me give you a concrete example of how the unthinkable can become thinkable in a quasi-legal context. On July 25, 2019, Trump had his notorious phone call with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, in which he asked Zelenskyy to “do us a favor” and investigate Hunter Biden, then withheld military aid that Congress had already allocated.

On reading the transcript, I (and many others) found it unthinkable that a president could lawfully engage in what appeared to be a textbook example of corruption. This view ultimately led me to testify before the House as part of the impeachment process. My testimony addressed what “high crimes and misdemeanors” means in the Constitution, a definition that (to me) plainly included a president corruptly using his foreign-affairs powers for personal political advantage.

After Trump was acquitted in what was largely a party-line vote, what had once seemed unthinkable suddenly seemed less so.

Ask yourself what you now think about Trump’s first impeachment. Is it still unthinkable that a president could do what he did and not be convicted of high crimes and misdemeanors by the Senate? No — because it has now happened — and because Congress, not the courts, has the final say over what counts as an impeachable offense under the Constitution.

So now, when Trump engages in behavior that seems every bit as corrupt as the Ukraine call — or more so — we no longer automatically categorize it as unthinkable. Trump has floated the idea of having his Department of Justice pay him $230 million in taxpayer funds as compensation for the criminal charges brought against him under the Biden administration. “It’s interesting, because I’m the one that makes the decision,” he said. “It’s awfully strange to make a decision where I’m paying myself … Did you ever have one of those cases where you have to decide how much you’re paying yourself in damages?”

The framers of the Constitution would have found the notion that a president could order the government to compensate him profoundly antithetical to their principles. It is a form of corrupt self-dealing of precisely the kind they considered high crimes and misdemeanors. Yet today, no one is calling for impeachment on that basis.

The only thing that might have stopped us from accepting this kind of corruption as thinkable would be if such acceptance upended our overall understanding of how constitutional democracy functions. Since democracy continued to operate — at least superficially — after the first failed impeachment, acceptance became possible, and the unthinkable turned thinkable.

This brings us to the law as a barrier to the unthinkable. In general, trained lawyers share a framework that defines which legal ideas are thinkable and which are not. The legal community as a whole generally agrees on these boundaries. Most of the time, when someone proposes an idea that nearly everyone regards as unthinkable, it is quickly rejected.

Once in a while, however, an initially unthinkable idea gains traction. In 2012, Yale Law School professor Jack Balkin wrote about how an unconventional legal challenge to the Affordable Care Act moved from “off the wall” to “on the wall.” He emphasized the sociology of the process — especially the willingness of prestigious lawyers with cultural capital to associate themselves with arguments that were once considered off-the-wall.

Balkin was right to highlight sociology, but he understated the psychological aspect of thinkability. Lawyers can only treat an unthinkable idea as thinkable if it doesn’t upend their broader conception of the law and how it operates. If they can’t reconcile the new idea with their broader worldview, it can’t become thinkable. That’s why lawyers proposing previously outlandish arguments always try to fit them into an existing legal framework.

It follows that the way to fight back against unthinkable legal ideas is to demonstrate precisely how adopting them would break the broader framework on which constitutional law rests.

Take the idea that Trump could serve a third term by running for vice president and then having the new president resign. This is an unthinkable legal idea because we all understand that the 22nd Amendment prevents anyone from serving more than two terms. The amendment says you can’t be elected twice. It also specifies that a vice president who serves more than two years of his predecessor’s term can’t serve two full terms. Together, these provisions make it unmistakably clear that it would be unconstitutional for Trump to run for vice president and then take over from Vance.

If it were possible to get around this amendment by exploiting the framers’ failure to explicitly forbid someone from being elected president twice and then again as vice president, it would tear the fabric of constitutional law in a fundamental way. It would make it fair game to violate almost any constitutional provision through linguistic manipulation.

The Constitution also says that the president “shall hold his office during the term of four years.” Following that distorted logic, one might claim, for example, that a woman president could serve more than four years because the text uses the word “his” — or that a woman couldn’t be president because only a “he” can hold the office.

The upshot is that this kind of literal reading of the Constitution would fundamentally disrupt how the Constitution operates as the body of law. It’s clear why the unthinkable should stay unthinkable: Because embracing such ideas would render the entire structure of the law unable to function properly.

Keeping the unthinkable in the category of unthinkable is therefore not a hopeless task, whether in law or in politics. It simply requires deliberate effort to show people how accepting the unthinkable would upend their worldview.

____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Feldman is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. A professor of law at Harvard University, he is author, most recently, of “To Be a Jew Today: A New Guide to God, Israel, and the Jewish People."

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments