F.D. Flam: James Watson had a brilliant mind and a broken moral compass

Published in Op Eds

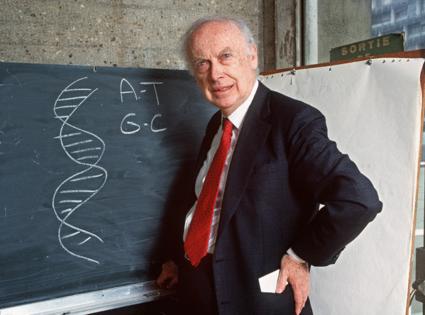

By the time James Watson died earlier this month at the age of 97, he was one of the world’s most famous — and infamous — scientists.

In 1953, he and three fellow researchers co-discovered the double-helix structure of DNA — a breakthrough that unlocked the secrets of how life works. The discovery revealed how a molecule could store and copy genetic information, providing a chemical mechanism for heredity, evolution and the immense diversity of life that gave rise to what Charles Darwin famously described as “endless forms most beautiful.”

But Watson’s legacy is complicated by his later history of bigotry and racism, including years of denigrating comments about people of African descent, women and gay people. His views first gained widespread public notice in a 2007 interview when he told the Sunday Times of London that he was “inherently gloomy about the prospects of Africa,” suggesting that Black people were intellectually inferior to White people. “All our social policies are based on the fact that their intelligence is the same as ours — whereas all the testing says not really,” he was quoted as saying.

The pattern continued in interviews, and in his 2007 book, Avoid Boring People — after which he was shunned by most of his former scientific colleagues. And yet, even as Watson clung to his racist and bigoted theories, the understanding of DNA’s structure and code-carrying function led to discoveries that dispelled such theories, showing that we all share a recent common origin in Africa.

I had the chance to hear Watson speak in 2005, two years before his racist views were widely known. It was during a field trip to the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island, which he had directed for 25 years and later served as its chancellor.

While I can’t remember his exact words, I do remember him boasting about the superiority of his own genetic heritage (Irish and Scottish) and his attributing problems in Africa to the genetic shortcomings of its people. Other journalists in the audience were shocked and puzzled. We thought he might be showing signs of dementia because it seemed implausible that he would say such things had he been in his right mind.

It wasn’t dementia. The biggest takeaway that day was that the people who make the most celebrated achievements in science may not always be endowed with either good judgment or wisdom — or even remotely know what they’re talking about in other arenas.

Watson was long known to make sexist remarks, but it wasn’t until the Times of London interview that the public backlash began in earnest. Though he quickly apologized he was eventually stripped of his position at Cold Spring Harbor.

He also made enemies with his entertaining but controversial 1968 bestselling memoir The Double Helix. His colleagues Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins were infuriated by the way Watson inflated his own contributions and denigrated theirs, as well as those of co-discoverer, Rosalind Franklin. Watson not only diminished Franklin’s scientific work but also made sexist remarks about her clothing and makeup.

Watson, Crick and Wilkins shared the Nobel Prize for the discovery in 1962. The prize is never given posthumously and Franklin had died from ovarian cancer in 1958 at the age of 37. But the world later recognized the vital importance of her use of X-rays to gather clues about the structure of DNA.

DNA’s double-helix structure — like a twisted ladder — allows it to store information along its rungs. Those rungs are made up of pairs of four different chemical building blocks, called bases — adenine, thymine, cytosine and guanine (A,T,C and G). Each base binds to a specific complementary partner: if there is an A on one side, the other side contains a T; if it is a C, the other contains a G.

The code is a long one. Human beings carry a string of code roughly three billion letters long in our 23 pairs of chromosomes. The ladder can reproduce by unzipping down the middle, allowing complementary pieces to assemble themselves. New variation emerges from reshuffling segments of DNA in sperm and egg cells, and from copying errors known as mutations.

Watson also served as the initial leader of the Human Genome Project — an effort to decode genetic information from a sample of people. That project led to new technologies that enabled scientists to analyze, compare and eventually reconstruct and engineer DNA.

The study of DNA has helped dispel racist ideas that had been promoted by earlier generations of scientists. In 1758, Swedish biologist Carolus Linnaeus not only created detailed classifications of plants, animals and other life forms, but also proposed four categories of humans that corresponded to ancestry in Europe, Asia, the Americas and Africa. These divisions were used to justify slavery and colonization.

In 1859, Darwin overturned humanity’s understanding of the living world and our place within it. In his book On the Origin of Species, he observed that the four-race classification scheme was arbitrary. He suggested that people might just as easily be classified into 168 different races, or only two. But some leading scientists persisted in arguing that humans could be divided into separate species.

By comparing DNA from people around the world, scientists eventually showed that all humans belong to a single, closely related species with a shared ancestry in Africa dating back only about 100,000 years.

More detailed DNA comparisons were published in 2016 in Nature — the same journal that originally announced the discovery of DNA’s structure. While fossils indicated that humans had been migrating out of Africa for hundreds of thousands of years, genetic evidence showed that today’s populations all descend from the most recent waves of migration, occurring between 50,000 and 80,000 years ago. DNA comparisons also revealed that the dividing lines historically drawn between those four races have no genetic or biological foundation. Our racial divisions are like the political borders drawn between countries with no grounding in geography. They only exist because people created them.

Some still use Watson’s scientific authority to justify their own racism, while others insist he simply stole credit from Rosalind Franklin. Watson’s biographers maintain that he does deserve recognition for uncovering how the structure of DNA functions — but again, sometimes a brilliant insight and a series of deeply flawed ideas can come from the same mind.

____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

F.D. Flam is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering science. She is host of the “Follow the Science” podcast.

_____

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments