Lisa Jarvis: This flu season doesn't have to be as deadly as the last

Published in Op Eds

Last year’s flu season was long, brutal, and ultimately tragic. By the time infections had subsided in May, as many as 1.1 million Americans were estimated to have been hospitalized and as many as 100,000 had died. Among them were 280 children — the highest number recorded in a non-pandemic year since health agencies began tracking the virus in 2004.

Some of that misery was likely avoidable.

Over the past few weeks, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has released a series of reports analyzing last year’s flu season, and together they point to one simple way to ease the burden of the infection: get more Americans vaccinated against the virus.

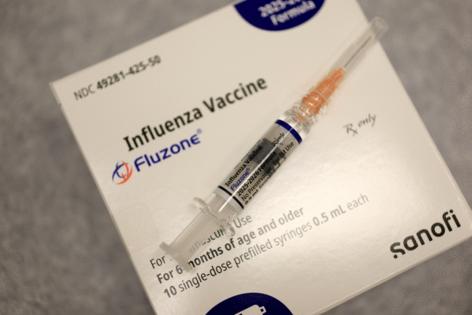

That needs to happen soon. October marks the official start of flu season, but the virus has yet to start spreading widely. Because the shot, which the CDC recommends everyone six months of age or older receive annually, offers the best protection when people get it before the virus begins circulating, now is the time to get vaccinated.

Last season, the flu started picking up in November, but really peaked in February 2025, when entire schools were forced to shut down and some hospitals were more crowded than they’d been during parts of the Covid-19 pandemic.

A CDC analysis of hospitalized flu patients across 14 states found that nearly 90% had at least one underlying condition—and yet fewer than a third had received a flu shot. Other CDC data reveal a particularly troubling trend: a steady decline in vaccination rates among vulnerable groups. Flu vaccination rates among pregnant women have dropped consistently since the 2019-2020 flu season, when nearly 57% of pregnant women were vaccinated, compared to last year’s nadir of 38%.

Meanwhile, less than half of children received a flu shot last year, according to CDC estimates. Notably, among the children old enough to be vaccinated who died, nearly 90% had not gotten a flu shot.

A reluctance to get the flu vaccine isn’t new. A 2019 survey of parents found that more than a quarter were hesitant about it. Some don’t consider the flu a serious threat, while others worry about the safety of the shot or mistakenly believe the vaccine can actually give them the virus.

And some doubt the vaccine’s effectiveness. In that same survey, only 1 in 4 parents believed the shot worked. That’s understandable. Many of us know someone who’s gotten sick — or have ourselves been knocked out by the flu — despite being vaccinated. Yet even when seasonal flu vaccines aren’t a perfect match for the strains in circulation, they still do a good job of keeping people from suffering the worst effects of infection.

An initial analysis of this year’s vaccine in the Southern Hemisphere — which experiences flu season from March to September and offers a preview of how well shots might work in the U.S. — underscores why vaccination really matters. Early CDC data suggest the shot reduced hospitalizations and flu-related outpatient visits by roughly half.

But convincing the public that their illness could have been far worse if they hadn’t given their immune system some target practice against the virus has long been a public health challenge. In fact, amid broader vaccine hesitancy following the pandemic, the CDC held focus groups to craft a new message. In 2023, it launched the “Wild to Mild” campaign that emphasized the shot’s ability to “tame” the virus. In theory, the campaign aimed to tackle two problems at once: a lack of education about the vaccine and lack of trust in public health agencies.

Unfortunately, last February, just as flu rates were soaring, the Trump administration pulled the campaign. A Health and Human Services spokesperson said via email that the program would be replaced this fall with “a new national outreach campaign designed to raise awareness and empower Americans with the tools they need to stay healthy during the respiratory illness season. This effort builds on CDC’s trusted guidance for flu, RSV, COVID-19, and other respiratory illnesses, reinforcing practical prevention steps.”

That shift in strategy is particularly concerning given new data showing that parents need more educating on the dangers that flu poses to children — even healthy ones — and the role vaccination can play in mitigating those risks. A recent poll conducted by KFF and the Washington Post found that only 27% of parents considered the flu shot to be “very” important, while another 29% considered it “somewhat” important.

Of course, the broader climate of skepticism around vaccines within this health administration leaves little reason to hope it will deliver a clear and forceful endorsement of the shot this fall. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has previously spread false claims about the vaccine, asserting that it transmits the flu and does not save lives.

Meanwhile, the CDC’s vaccine advisory panel further undermined confidence by removing its recommendation for shots containing thimerosal, despite decades of data affirming their safety. Although those formulations are used by only a small percentage of the population, medical groups fear the move will erode trust even further and sow additional doubts about the flu vaccines overall.

This struggle to boost flu vaccination rates is nothing new, but today’s environment makes the challenge even tougher. Let’s hope the nation’s most trusted messengers — frontline physicians offering the most trusted advice — are able to cut through the rhetoric and turn things around.

_____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Lisa Jarvis is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering biotech, health care and the pharmaceutical industry. Previously, she was executive editor of Chemical & Engineering News.

_____

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments