Commentary: Getting fired for social media posts is the new workplace cancel culture

Published in Op Eds

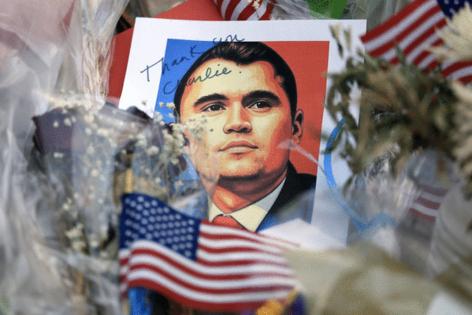

Americans think the First Amendment protects their speech. It doesn’t — at least not at work for most of us. Just ask the executives, teachers, lawyers and even a Secret Service agent disciplined after posting about the assassination of conservative activist Charlie Kirk. A single Facebook update or tweet — whether mocking, angry or careless — can now end a career overnight.

The line between our personal and professional lives has collapsed. Strangers online don’t just argue over posts they find offensive; they forward them to employers with a single demand: fire this person. What began as a left-leaning push to oust employees for racist or sexist remarks has become a bipartisan weapon. Conservatives, once critics of “cancel culture,” now deploy the same tactics. In many ways, the rooster has come home to roost: outrage, once one-way, is now a two-lane highway.

This isn’t new. In 2013, public relations executive Justine Sacco made a crude AIDS joke on Twitter before boarding a flight. By the time she landed, she had lost her job and become a global pariah. In 2017, comedian Kathy Griffin was dropped by CNN after posing with a mock severed head of Donald Trump. Even corporate titans aren’t immune: CrossFit founder Greg Glassman was forced out in 2020 after dismissive tweets about George Floyd and COVID-19. Ordinary workers face the same risks with fewer safety nets. A Texas nurse was fired after posting in an anti-vaxxer group about a measles patient — even though she never named the child.

The question is stark: Do Americans really have the freedom to speak their minds outside of work or does at-will employment make every social media post a liability?

For most private-sector employees — nearly 90% of the workforce — the First Amendment offers no protection. The Constitution restrains government, not private companies. Employers can fire workers for almost any reason, including speech, so long as it isn’t an illegal basis such as race or religion.

Employers know the risks. Many enforce strict social media policies. In an era in which a viral screenshot can undo years of branding, businesses often fire first and ask questions later.

Some protections exist, but they are weak and inconsistent. Public employees have limited First Amendment rights, but those vanish if speech disrupts the workplace. Labor law protects “concerted activity” about working conditions, but those cases are rare. A handful of states, including Illinois, California and New York, prohibit firing workers for lawful off-duty conduct, but courts have barely tested these laws. Contracts may require cause for firing, but many contain broad morality clauses or social media restrictions.

Taken together, these protections sound reassuring on paper. In practice, they are narrow, untested and riddled with loopholes. Once an online outrage cycle begins, little can stop it from costing someone their job.

This has created a chilling climate in which online expression carries profound risks. What once felt like idle chatter can ricochet into a viral scandal, amplified by partisan networks and advocacy groups. Increasingly, activists pressure not just employers but also their customers, urging boycotts unless the company cuts ties with the employee. What begins as a reputational problem for a worker becomes a commercial risk for the business.

To some, this is accountability: Words have consequences, and companies shouldn’t associate with hateful or violent speech. To others, it’s mob justice, in which the loudest voices online dictate who deserves a paycheck. Either way, the trend is accelerating.

Workers should assume their online lives are not separate from their professional ones. Privacy settings offer little real protection. Employers fire based on perception, not nuance. The only safe advice is pragmatic: Think before posting, especially about polarizing events.

Some common sense legislation could help. Workers should not lose their jobs over private online activity that has no bearing on their work if they post responsibly. A straightforward rule: If an employee keeps a post private, and the employer cannot show that it is job-related or materially harmful to the company, firing should not be permitted. Employers would still act when truly necessary — for threats, harassment or reputational damage — but careers wouldn’t be destroyed over personal views in limited, non-work settings.

The burden shouldn’t fall entirely on workers. If social media platforms can nudge us to drink water or stand up, they can also remind us of the professional risks of posting when a controversial topic is raised. Before someone can publish a social media post, why not a pop-up? “Remember: this may be visible to your employer and could affect your job.” It wouldn’t solve cancel culture, but it would give people pause before publishing something that might end their career.

The deeper problem is cultural, not legal. Free speech hasn’t disappeared — it has been privatized. Americans remain free to say almost anything, but our livelihoods now depend on how the internet reacts.

That’s not sustainable. We need a public debate about whether employment should be so precarious that a single post can erase someone’s career. Until then, every post carries a warning, whether written or not: Proceed at your own risk.

____

_____

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments