Mark Gongloff: $1 trillion in American wages has gone up in wildfire smoke

Published in Op Eds

The climate emergency has produced several on-the-nose metaphorical moments lately, such as an art museum founded by oil baron J. Paul Getty being threatened by the Palisades fire in Los Angeles in January or a superyacht’s fireworks sparking a wildfire in Greece last year. But nothing tops how more than $1 trillion in U.S. wages has gone up in literal smoke from fires hundreds of miles away, according to a new study.

It’s a reminder that climate change is no longer a problem for our grandchildren but is inflicting profound economic and health damage right now. It’s also a reminder there are few if any places to hide from the consequences of our failure to address this crisis.

From 2020 through 2024, U.S. workers in the retail, wholesale, transportation, construction, mining and agriculture industries alone lost $1.1 trillion in wages because of exposure to wildfire smoke, according to a new estimate by Bloomberg Intelligence. Analyst Andrew John Stevenson focused on these industries because they’re the most exposed to smoke, which causes people to miss work and generally be less productive. (It’s not easy to drive a truck or a bulldozer when you can’t breathe.)

Wages in these industries represent just $2.8 trillion out of $11.4 trillion in total U.S. wages, BI notes. In other words, to the extent other industries suffered from smoke, that $1.1 trillion in losses will be higher — possibly much higher.

The BI estimate is based on a 2022 National Bureau of Economic Research paper suggesting one day of exposure to wildfire smoke reduces a person’s quarterly wages by roughly 0.1%. Expose enough people to smoke for long enough, and pretty soon you’re talking real money. In 2023, for example, Americans suffered through 150 smoke days, thanks to a record wildfire season in Canada. That cut the wages of BI’s chosen industries by $407 billion that year alone. That group’s wage losses over the past five years are almost six times as high as between 2006 and 2010.

Typically, the fire-prone West Coast has been the most vulnerable to wage impacts from smoke. But the recent surge in Canadian wildfires has shifted that burden to the U.S. Midwest, where workers in vulnerable industries are especially concentrated. In some counties in Minnesota and the Dakotas, more than a quarter of all wages in these industries were lost in Canada’s record fire season of 2023, according to BI.

Smoke from the 2023 fires caused the worst air pollution in the U.S. since 2011, according to a recent University of Chicago study. Counties in Alaska, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, and Texas replaced California counties in the ranks of the most-polluted places in the U.S. that year.

This year is turning out to be another bad one for Canada, with 8.3 million hectares (or 21 million acres) burned so far, according to the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre, on pace to be at least the second-worst season ever. Smoke from these fires has taken air quality across the U.S. to levels not seen since those dark (orange) days of 2023.

Wildfire smoke is a nightmare for human health, 10 times more toxic than regular pollution, according to Stanford University researchers. Its particulate matter attacks not only lungs but all other organs, contributing to heart disease, cancer, dementia, low birth weights and more.

It causes emergency-room visits to surge, especially by uninsured people. Those costs are a blow to municipal health-care borrowers, a recent Dallas Federal Reserve study noted. Hospitals and nursing homes in high-smoke areas paid an extra $250 million in interest due to wildfire smoke alone between 2010 and 2019, according to the study. That could more than double to $570 million in the next decade. As with wage impacts, the hit to borrowers has shifted from the West Coast in recent years. In 2023, for example, some health-care borrowers on the East Coast faced five times more smoke exposure than they did between 2010-2019, according to BI.

Wildfires have broken out for as long as there have been trees and lightning, of course. And humans are responsible for setting most fires. But a hotter planet makes those fires more likely and intense by making air hotter and foliage drier. In parts of the U.S., wildfire season is now two months longer than it was in 1973, according to the research group Climate Central. The U.S. acreage burned each year has doubled in the past 20 years from its average between 1983 and 2004, according to the National Interagency Fire Center.

Meanwhile, the amount of toxic wildfire smoke that Americans in the Lower 48 states have been exposed to has also doubled in the past five years from the levels in 2006-19, according to researchers at Stanford and the University of Washington. Smoke deaths alone could inflict $244 billion in annual U.S. economic damage by 2050, according to an NBER paper last year.

Wildfire smoke can’t be avoided or contained, though better forest management and wildfire response can help limit it. Burning fewer fossil fuels, thus slowing the pace at which we’re heating the planet, will also help.

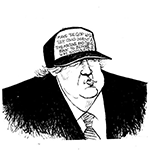

Instead, President Donald Trump’s administration relentlessly attacks the clean energy industry, environmental standards and anything else related to climate change while slashing funding for federal disaster response and health research. All of this is being done in the name of favoring economic growth over “wokeness.” But until we treat wildfire smoke and climate change like the metastasizing national health emergencies they are, both our physical health and economic growth will continue to be stunted.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

•America’s Wind Crusade Hands China an Industry: David Fickling

•Wildfire Firefighters Are Getting a Helping Hand: Lara Williams

•Fossil-Fuel Supporters Have an Odd New Narrative: Liam Denning

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Gongloff is a Bloomberg Opinion editor and columnist covering climate change. He previously worked for Fortune.com, the Huffington Post and the Wall Street Journal.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments