Andreas Kluth: Even nuclear experts are at a loss right now

Published in Op Eds

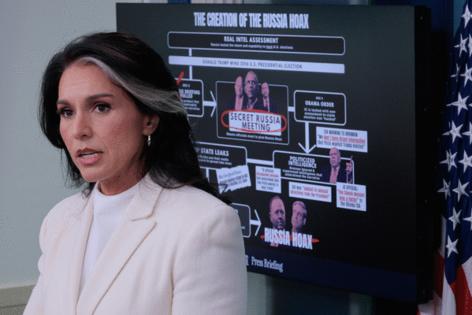

Tulsi Gabbard, the U.S. director of national intelligence, admittedly struck the wrong note in a melodramatic video she put out after visiting Hiroshima, which was destroyed by an atomic bomb exactly 80 years ago.

“As we stand here today, closer to the brink of nuclear annihilation than ever before,” Gabbard said, “political-elite warmongers are carelessly fomenting fear and tensions between nuclear powers.” That reference to unspecified warmongers hewed to her unfortunate pattern of spreading conspiracy theories. Her boss, President Donald Trump, wasn’t pleased.

But Gabbard was right about her other point: that we — Homo sapiens — may be closer to the brink than ever before. That’s what I keep hearing from experts on nuclear strategy in Washington. The danger today may not be as acute as it was during the Cuban Missile Crisis. But it is much more diffuse, complicated and unpredictable than it has ever been. And while those in the know can summarize how we got to this point, nobody, as far as I know, has any good ideas about where to go from here.

The diagnosis is essentially a long list of separate but simultaneous developments that collectively upset the relatively simple balance of terror that stabilized the late Cold War.

At that time, two nuclear superpowers held each other in check while a few other nations kept small arsenals for deterrence and almost all other countries abided by the Non-Proliferation Treaty, meant to limit the spread of these diabolical weapons.

Entire ecosystems of expertise had blossomed in academia and government to model the scenarios that might lead to Armageddon, and the resulting game theory, though sophisticated, was relatively straightforward. Stipulating that a nuclear war “cannot be won and must never be fought,” the big two — Washington and Moscow — negotiated arms-control treaties to reduce the number of warheads and weapons. After the Cold War, strategists shifted to studying other threats — terrorism and such — because nuclear annihilation seemed passé.

Instead, it tops the horror rankings again. The last remaining arms-control treaty between Washington and Moscow, called New START, expires in six months, and no efforts are underway to extend or replace it. One of the two parties, Russia, has been acting in bad faith and breaking nuclear taboos by threatening to use lower-yield weapons (sometimes called “tactical” or “battlefield” nukes) in Ukraine and stationing warheads in neighboring Belarus.

Worse, a third nuclear superpower, China, is turning the former dyad into a triad. Whereas Beijing long maintained only a minimal deterrent, it has in recent years doubled its arsenal to about 600 warheads and is rapidly adding more, with the apparent goal of having 1,500 or so in a decade — roughly as many as the U.S. and Russia each currently have deployed.(1)

This new reality forces strategists in Washington to contemplate what would happen if Russia and China ever coordinated attacks on, say, Eastern Europe and Taiwan. Such a two-front war could start “conventional” (meaning non-nuclear) but escalate to the use of battlefield nukes, at which point further escalation spirals become incalculable.

The U.S. is already modernizing — albeit with huge delays and cost overruns — its missiles, bombers, submarines and warheads. Should it now also add to its arsenal overall, to deter or be able to fight both Russia and China at once?

Experts agree that nuclear deterrence is not a pure numbers game (all sides would soon just be irradiating rubble). And game theory is far from clear about what is stabilizing and destabilizing in the real world; the math in such a “three-body problem” becomes forbidding.

Nor does the number three capture the horror of this analytical hairball. In total, nine countries have nukes. And even if the recent American strikes on Iran set back Tehran’s program for a while, other countries may build their own. They could include U.S. allies, such as South Korea or Poland, if they lose faith in the U.S. nuclear “umbrella.”

More players mean more scenarios for people to miscalculate. (An especially dangerous period is the phase when countries are making nukes but do not yet have them because adversaries may contemplate preemptive strikes.) North Korea can already hit the U.S. with its weapons; and Washington believes that Pakistan is also building missiles that can reach America.

Even that catalog doesn’t do justice to the new threat landscape because the types of warheads and delivery vehicles are changing. For example, more countries are investing in those tactical nukes I mentioned, which are “limited” only in theory but in practice likely to set off uncontrollable escalation to full-scale nuclear war.

China is also building hypersonic glide vehicles which, unlike ballistic missiles, can circle the Earth inside the atmosphere and disguise their destinations. Russia is thinking about putting nukes in space. And Trump wants to place a defensive “Golden Dome” up there, which would pose its own strategic problems.

Add to these twists the imponderable of artificial intelligence, which drastically accelerates human decision-making and thus increases the potential for human error, especially under pressure. Those risks become even worse wherever AI meets misinformation. (During the recent clash between nuclear-armed India and Pakistan, fake photos of damage went viral in both countries.) Scientists warn about the combination of misinformation “thickening the fog of war” and “giving the launch codes to ChatGPT.”

Bright minds are studying these developments, including Vipin Narang and Pranay Vaddi, two nuclear experts who served in the administration of Joe Biden and are now at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. But diagnosis is one thing, prescription quite another. The U.S. “will need innovative approaches,” they conclude — without listing any.

“We’re approaching a tripolar world, and everything is different in that scenario,” says John Bolton, who was national security advisor in Trump’s first term. “All of our calculations on nuclear weaponry, the nuclear triad, where the stuff is deployed, how you create structures of deterrence,” he told me, “how you engage in arms-control negotiations, all of it, all of that theorizing … all of that is on a bipolar basis.” Then he added dolefully: “You make it tripolar and you got to start over again.”

Trump seems to have grasped this reality. He has said repeatedly that he wants to restart arms-control negotiations and that he wants them to be at least trilateral, including both Russia and China. Whether his counterparts in Moscow and Beijing will rise to the occasion is unclear.

Much divides those three leaders, and indeed humanity. But if we can’t agree to sequester our hatreds and vanities to deal with this singular threat, none of those other things will matter.

(1) “Deployed” means ready for use at any time — for instance, on the tip of a missile in a silo. Washington and Moscow also have thousands more in storage each.

_____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andreas Kluth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering US diplomacy, national security and geopolitics. Previously, he was editor-in-chief of Handelsblatt Global and a writer for the Economist.

_____

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments