Commentary: Let states take the lead on voter verification

Published in Op Eds

President Donald Trump recently signed an executive order intended to ensure that only eligible citizens can vote in U.S. elections. While we laud the purpose of the order, a better approach would be to look at how states are using data that they already possess to determine a voter’s citizenship, and identify ways that the federal government could provide additional assistance.

The executive order mandates that people provide proof of citizenship in order to register to vote anywhere in the country, and entrusts a federal agency — the Election Assistance Commission — with implementing the overhaul of the system. Currently, states set their own voting policies, and the Constitution tasks them with administering their own elections. Lawsuits have been filed to block the executive order, and the likelihood of a successful implementation of the order after it has been completely adjudicated is extremely low.

The White House said in a fact sheet that the order would “protect the integrity of American elections” by strengthening voter citizenship verification and ending “foreign interference in our election process.” In practice, however, the order has the potential to create numerous unfunded mandates that election workers would be forced to contend with, and the possibility of creating other unintended consequences.

As conservative Republicans and former secretaries of state responsible for administering elections in two Southern states, we have seen this dynamic play out in real time. Our experience has taught us that, thankfully, noncitizen voting is rare — it is already illegal in federal elections and is only authorized in a few local jurisdictions.

But there is still much that can be done to ensure that it stays low. Those who are interested in getting the citizenship issue right can look to the states for promising pathways forward. What these efforts have in common is that they put the onus on state officials to ensure that rolls are free of noncitizens, rather than relying on people registering to vote to prove their citizenship. To date, there is no mechanism in place to easily allow states and local jurisdictions to confirm citizenship.

In Oklahoma, for example, the state legislature passed S.B. 1040, which applies a so-called citizenship filter to the state’s voter registration procedures. What the law does, in effect, is prohibit state employees from registering any residents to vote if they have provided documentation that demonstrates they are not a U.S. citizen. While this may seem like common sense, language barriers, unfamiliarity with the relevant documentation and clerical oversights can often result in noncitizens being inadvertently offered the opportunity to register.

Idaho’s proposed H.B. 339, if passed, would “ensure that only eligible Idaho voters are registered to vote in Idaho” by requiring that all registering voters be cross-checked against citizen databases. If a voter’s citizenship status doesn’t match with the database, they would be removed from the rolls. Secretary of State Phil McGrane has said his office removed several dozen noncitizen voters while acknowledging that “this is very rare, it’s very limited.” This comes after Idaho voters approved a constitutional amendment barring noncitizen voting last year.

In Missouri, there are two bills under consideration that, taken together, would help to rebuild confidence that voter rolls are secure and up to date. S.B. 62 would require “documentary proof of United States citizenship … in order to register to vote.” And S.B. 280 would require the relevant state agencies to screen driver’s license recipients for citizenship status before they are provided with a voter registration application form. Again, while this seems like common sense, codifying it into law helps head off potential red tape and bureaucratic issues in the future.

In Georgia, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger conducted an audit last year to verify the citizenship status of eligible voters and root out noncitizens. The state says it has now successfully implemented a system within its motor vehicle administration to verify citizenship status. In February, Raffensperger sent a letter to the Department of Homeland Security regarding the Safeguard American Voter Eligibility (SAVE) act — legislation that, if passed by Congress, would impose sweeping changes to the nation’s election system — urging federal officials to “remove some of the current burden states face in using SAVE as a tool for citizenship verification.”

What these and other successful state-level policies understand is that there can be unintended consequences to introducing new citizenship requirements. Most people agree that we need to ensure only U.S. citizens vote, but many fail to consider the second-order effects of less-targeted policies aimed at doing so. In one noteworthy case, in Kansas, state officials found that most of the 30,000 citizens who were removed from voter rolls under state law were, in fact, eligible U.S. citizens.

To take another example, married women who are U.S. citizens could be mistakenly purged from the rolls under the SAVE act because of discrepancies related to changing their last names. In many cases, these voters skew disproportionately Republican, meaning that GOP-led voter integrity efforts could end up removing eligible Republican voters from the rolls .

It is also critical to remember that, in addition to new voter ID laws, many states are working with out-of-date election technology and little or no funding available for modernization. Based on our years of experience administering elections, we know that officials can only do so much with limited resources. By freeing up additional funds and connecting states with federal databases to cross-check voter information, states can better position themselves for success.

The Republican majority in Congress has an opportunity to increase election funding by passing $75 million in new election-security grants. This money would be used for cybersecurity protection against foreign threats, staffing, purchasing new vote-counting equipment, updating registration systems and more.

At the same time, it’s important to point out that, fortunately, noncitizen voting is historically rare. In states where such fraud has been investigated, very few instances have been found in the modern era. Yet those in charge of administering elections must contend with the fact that a critical mass of the voting public harbors serious concerns about election integrity in general, and noncitizen voting in particular.

For these reasons, we co-chair the Secure Elections Project, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization dedicated to keeping elections safe while ensuring everyone has fair access to voting in their lawful jurisdiction. Thankfully, as we’ve seen, it’s possible to take voters’ concerns seriously at the state level — while maintaining the right of eligible U.S. citizens to cast a legal ballot.

_____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

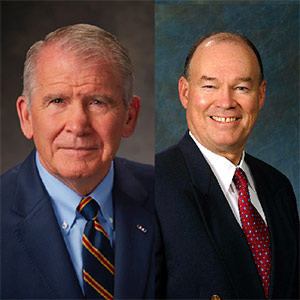

John H. Merrill, a Republican, was Alabama’s secretary of state from 2015-23. He is co-chair of the advisory board at the Secure Elections Project and is the principal of Morning in Alabama Consulting LLC.

Trey Grayson, a Republican, was secretary of state for the Commonwealth of Kentucky from 2004-11. He is co-chair of the advisory board at the Secure Elections Project and a partner at Frost Brown Todd LLP.

_____

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments