Mihir Sharma: USAID is in dire need of reform. But not like this

Published in Op Eds

President Donald Trump’s abrupt “pause” to all U.S. foreign aid, alongside his adviser Elon Musk’s attack on the personnel and institutions of the United States Agency for International Development, has unleashed chaos across the globe. Many of the world’s poorest and most vulnerable people seem to have been deliberately left stranded without the help they were promised. That this mayhem has been launched by a U.S. president, and greeted with relish by many of his voters, will unquestionably dent American prestige and power.

That’s a pity. Because reform and restructuring of U.S. development assistance was long overdue. Here in India, as in much of the world, a modern approach to development assistance from Washington with a more equal partnership, and one informed by geopolitics and mutual interest, would certainly have been welcomed.

Questions about the usefulness of 20th century-style aid in the 21st century aren’t unique to Trump’s circle, or even to the U.S. In 2020 Britain, for example, merged its development agency into its foreign office and closely aligned their purposes and activity. Even some generous Nordic countries, including Denmark and Sweden, have moved to curb the independence of their overseas agencies, concerned that too much taxpayer money was going to unaccountable progressive NGOs.

These countries may have changed how their aid operates and reduced bureaucrats’ independence. But nobody in the developing world saw that as a sign of churlishness or insularity. Britain, after all, remains committed enough to international development to largely maintain a decades-old spending promise even through biting austerity and crisis.

The reason development assistance should dovetail more closely with foreign policy is not to ensure that aid becomes an arm of politics. More often, it is to ensure that aid survives politics.

Development assistance can never be entirely apolitical. The moment you spend money in a developing country, you create new interest groups and, sometimes, disadvantage old ones. You need to find partners within local establishments that help you identify how and where to spend the money; in the process, you empower those people.

Musk and others might claim that the problem is that USAID was pushing through progressive priorities like reproductive health and minority rights. Whether or not that is true, it misses the point. Even if you’re going after entirely laudable health or education priorities of which everyone approves, you will have to work through existing institutions or displace old ones. And each time you do, you’re making decisions that have a political impact.

If bilateral grants don’t just impact a country’s development but also its politics, then you need the diplomats around to make sure that it doesn’t work at cross purposes with your broader plans in that country. And you also need the diplomats to ensure that the country’s leaders don’t think your work is crossing some red line that your aid bureaucrats haven’t been told about.

In other words, USAID — like all bilateral development agencies — is not a charity or a non-governmental organization, but a state agency and a political actor. That is precisely what Secretary of State Marco Rubio has accused it of forgetting. Rubio said that diplomats told him: “They [USAID] undermine the work that we’re doing in that country; they are supporting programs that upset the host government for whom we’re trying to work with on a broader scale.”

Rubio, as the new acting administrator of USAID, should indeed get to work fixing that problem. It’s something that developing-world governments would be happy to partner with the Trump administration in achieving. But the chaos at USAID doesn’t fix that problem; it creates new ones for the U.S.

It may be a bad look to have an agency working at cross-purposes with your diplomats. It’s far worse to appear to not care at all for your promises and commitments.

Reducing your budget is not a disaster. France and Germany are both planning to slash their development assistance drastically, but that will not impact how they are seen half as much as Trump’s action will shift perceptions of the U.S. Cuts are only a problem if you go out of your way to inflict pain when making them.

Many in the developing world, including India, are sympathetic to the second Trump administration’s broader aims – reworking global trade, combating China, restoring relations with Russia. They think these are good ideas, as is the reform of USAID.

But what’s the lesson they will take from the past weeks? That even good ideas might purposefully be implemented poorly and disruptively, whether to grab headlines or inflict political damage on opponents at home.

Rubio, at least, understands how development assistance works, and what needs to be fixed. He needs to get to work doing that — so that the new president’s policy priorities can be protected from his administration’s own worst instincts.

____

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

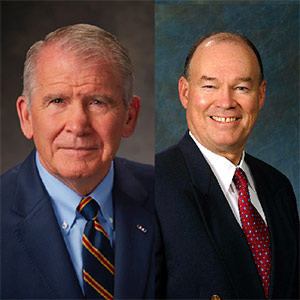

Mihir Sharma is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. A senior fellow at the Observer Research Foundation in New Delhi, he is author of “Restart: The Last Chance for the Indian Economy.”

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments