Gone global: Detroit-style pizza lands on four continents ... and counting

Published in Variety Menu

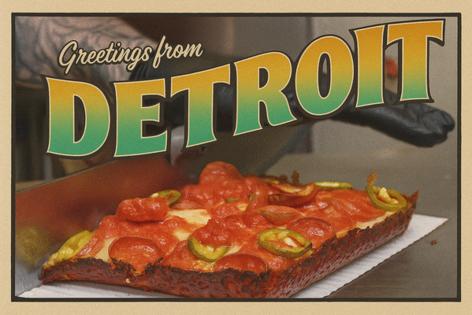

DETROIT -- Nate Peck peered over his shoulder at the oven, where the cheese lining the edges of one of his Detroit-style pizzas was caramelizing into its final, flaky form.

He recalled a recent visitor to his restaurant: a chef from New Zealand, of all places, hoping to expand his menu by learning the craft of Detroit-style pizza. Peck spent days with Brad Mackay, demonstrating how to make the airy, focaccia dough, and shopping with him for his trade's necessary tools — rectangular steel pans.

Peck and Kristen Calverley, co-owners of Michigan and Trumbull Pizza in Detroit, say they were happy to instruct Mackay because they're not "territorial" about their recipe. If anything, they've seen enough "bad imitations" of Detroit-style pizza and wanted to stop more.

Their ambassadorship for the Motor City's iconic pie is the latest chapter in the growing saga of its global expansion. Restaurants billing their pizzas as "Detroit-style" have sprung up all over the world, mostly in the last five years, from Toronto to Mexico City, London to Berlin, Dubai to Seoul and Adelaide, Australia.

The proliferation of Detroit-style pizza, long guarded by its protective stalwarts, builds on its increasing popularity in the United States. In 2022, Little Caesars launched an ad campaign touting its Detroit-style pizza as "actually from Detroit" because restaurants selling it appeared in nearly all major American cities.

It's difficult to explain how the Detroit-style pizza diaspora evolved, but serendipity and the internet may deserve some of the credit. Still, much of the expansion can be traced to one late chef intent on proselytizing Detroit-style pizza to the rest of the world, according to two authors who have researched it extensively.

With replication comes responsibility, the researchers and local chefs said. Detroit's history colors that duty: decades of tumult and miserable comparisons to other American cities heighten the need for icons the city can embrace.

But what makes a pizza Detroit-style is largely what a chef says it is. That makes it difficult for chefs abroad to distill its true essence.

"You'll never find a consensus," said Gail Offen, a Michigan-based author who has written extensively on the state's culinary traditions. "It's as divisive as politics."

That's why many in Detroit feel that as long as chefs in far-flung lands make an earnest attempt to get it close enough, they're in the Motor City's good graces.

"Every time you say Detroit-style pizza, you're repping Detroit," Offen said. "And maybe it's going to make (non-citizens) curious. As long as Detroit is in the conversation, I think that brings more people to Detroit."

Detroit-style pizza overseas

Among other things, John Marguiles makes a living selling Detroit-style pizza in Germany at his restaurant Magic John's Pizza at Oranienburger Str. 48 in Berlin. Growing up in New York, Marguiles didn't know the midwestern variety existed.

No, Marguiles knew Detroit for its music long before he learned of its pizza. He moved to Berlin in 2004 to open a nightclub, and it was through that venture that he discovered techno, the sub-genre of electronic music native to Detroit.

His enjoyment of techno meant Marguiles already had a positive association with Detroit. When he got back into the culinary game years later, he stumbled across a photo of Detroit-style pizza online.

"I said to myself, 'it looks like that, it comes from there,'" he said, "'it's gotta be good.'"

Now, around a third of his business comes from selling Detroit-style pizza in Germany. Marguiles laments that he's never been to Detroit, but considers his pizzas an "homage" to a city he holds in high esteem — especially given the parallels to his adopted hometown of Berlin.

Dae Young Kim owns the restaurant Motor City in Seoul, South Korea. He tried out Detroit-style pizza in 2015 to differentiate his restaurant from a Korean market "saturated" with Italian-style and Chicago-style pizza. His business partner travelled to the United States to attend a seminar taught by Shawn Randazzo, the late evangelist of Detroit-style pizza.

Kim encountered doubters who claimed there was "no competitive advantage and local people do not like deep-dish pizza," but he pressed forward anyway. Kim wanted to "challenge the market with the mindset 'Detroit Hustles Harder,'" the company's slogan.

And Down Under in Adelaide, Australia, Charlie Lawrence serves "cheffed up" versions at his restaurant Square Slice Pizza: "I think it’s a great canvas to experiment with ingredients and produce very exciting and good-looking pizzas."

His menu has included a Banh Mi pizza and featured exotic toppings like salmon, fennel seeds and smoked cheddar. Even the pepperonis he uses are unique, and are rarely, if ever, found on Detroit-style pizza: He imports "char and cup" pepperonis, the tiny ones that curl up to form a rim as grease pools in the middle.

The experience can be "educational" for customers, who are often wary at first that it will be "too heavy," Lawrence said. But he knows he's won them over when the Aussies take out their phones to snap pictures of the photogenic pies.

'Laying claim'

As Detroit-style pizza proliferated in the early 2020s, Karen Dybis spent two years of her life researching a book all about it, called "Detroit Style Pizza: A Doughtown History." Hers was a lofty endeavor, but one she felt immensely important. Documenting Detroit-style pizza's history was a means for the city to "lay claim to it" as it spread.

Enshrining that association was doubly important for Detroit, she said, given that it hasn't had as much to brag about in recent decades compared with the other American cities famous for their pizza, namely New York and Chicago.

In fact, Dybis is wary of cheap imitators of Detroit-style pizza and tries to stay on the lookout for them. And she looks for businesses making Detroit-style pizza, yet distancing themselves from the label. She cited as an example Emmy Squared, a chain mostly on the East Coast, but reportedly with two locations in United Arab Emirates.

The restaurant says its secret is to "combine a New York style grandma pie with a Detroit-style pizza and then (add) a dose of culinary creativity with our fluffy focaccia-like dough, edged with a caramelized, crispy cheese known as frico crust." Stalwarts of Detroit-style pizza might contend that focaccia dough and frico crust are staples of the pie, not a culinary flourish on top. (A representative of Emmy Squared did not respond to requests for comment.)

Still, Dybis acknowledged it could be unreasonable to expect sellers outside of Detroit to make the city's pizza authentically, when the originators themselves have had "internal squabbles" about what qualifies as the real deal.

One example: some contend Wisconsin Brick Cheese — which was used on the original Buddy's pies — is a must; others shrug it off. Some say sauce on top defines it; others are perfectly content to keep it under the cheese.

Calverley and Peck said their recipe is always "evolving," but one non-negotiable is blind baking versus par-baking. Par-baking means initially baking the dough partway through, then wrapping and storing it. Later, it's sauced, topped and baked once more to completion.

Par-baking generally allows chefs to produce a higher volume of pizzas more efficiently. But Calverley said the trade-off is a dry, "biscuit"-like texture, and a flimsy "frico" — the Italian word for the crispy, caramelized cheese around the pizza's edge.

She pulled up the Instagram page of a former competitor when they cooked in Pittsburgh. She zoomed in on the frico of one of that restaurant's pizzas, showing where it drooped off the side of the dough. That's because the initial par bake caused the dough to shrink inside the steel pan, Calverley explained, meaning the cheese couldn't be simultaneously spread to the sides of the dough and pressed up against the pan's walls — a crucial maneuver for a proper frico.

But some abroad consider par-baking an essential part of their take on Detroit-style pizza. Lawrence, the Australian, said the method is how he achieves the perfectly flat walls of caramelized cheese rising inches above the toppings.

"There is a very minor gap between the parbake and the pan," Lawrence said in an email. "The cheese melts and slides down between the base and the pan and sets there. We have spent a couple years perfecting our cheese blend and techniques to get the best possible cheese wall you can get."

A Detroit-style evangelist's legacy

Detroit-style pizza wasn't always destined to make it out of Motown. Rather, the three "OGs" — Buddy's, Loui's and Cloverleaf — were guarded about their recipes in the early days, said Dybis, the author.

Those restaurants were "feeding their families," so inviting any competition seemed imprudent, she said. Decades after the style was founded, though, one industrious delivery driver felt compelled to challenge such protectiveness.

Shawn Randazzo had been delivering pizzas for Cloverleaf in St. Clair Shores for a few years when the company's owner asked if he'd take ownership of the franchise, explained his mother, Linda Michaels. Randazzo and his mother teamed up and took the offer, prompting Randazzo to learn more about the pizza sector, traveling to industry events and competitions.

Michaels recalled how amazed Randazzo was at the 2009 Pizza and Ice Cream Expo in Columbus, Ohio, when "nobody there knew what a Detroit-style pizza was." Randazzo told The Washington Post in 2016 that some expo attendees — in disbelief about the existence of Detroit-style pizza — joked, "Does it have bullets in it?"

Not being taken seriously lit a "fire" under Randazzo, his mother said. He became hell-bent on launching a "pizza revolution."

His motivations were two-fold. For one, Randazzo thought "it's such a good culinary pizza, that everybody should have an opportunity to eat it," Michaels said. Beyond that, he wanted to combat the "bad rep" Detroit had endured most of his life, and to create "something positive coming out" of the city.

From there, Randazzo started training people to perfect the craft, reaching out to restaurants interested in trying it out. They included "Via 313," a chain in the western United States whose name is itself an homage to the Motor City's area code.

A decisive step forward in the "pizza revolution" came in 2012 with Randazzo's victory at the International Pizza Expo in Las Vegas, Michaels said. The win empowered Randazzo and his mother to start their own business — Detroit Style Pizza Co. — where the central goal would be to evangelize their beloved cuisine.

Michaels and Randazzo operated the company together for years, selling specialized steel pans to chefs around the world looking to try their hand. They offered training courses on how to make it, and, of course, served up their own out of the restaurant in St. Clair Shores.

"He started training people all over the world," Michaels said. Today, Randazzo's efforts are widely recognized in the pizza industry as popularizing Detroit-style pizza, according to Dybis and Offen.

Randazzo died of cancer in 2020. He was just 44. Today, Michaels and her sister carry forward Detroit Style Pizza Co. in his memory. During an interview with The Detroit News on a recent day in their small Roseville office — decorated with Randazzo's name plate, photos of him, and the plaque he won at the International Pizza Expo in 2012 — the two finished preparing a shipment soon to be picked up.

Michaels told a UPS driver in the doorway that they needed 10 minutes longer. "I can wait 10 minutes," the driver responded. "Awesome," the women replied in grateful unison, before Michaels gestured toward a freezer and implored, "well, pick a pizza!" Then, she read from the company's mission statement, which her son wrote years before his passing.

"Our mission is to increase awareness of Detroit-style pizza by serving an authentic pizza, sharing its history, educating others, and expanding our business while providing memories and opportunities," Michaels recited. For minutes after, as the interview went in other directions, she held on to the laminated document.

She listed a few elements that make a pie authentically Detroit-style (pepperonis on top of cheese, or underneath? "You could go either way") then stopped, and returned to Randazzo's words.

"I just wanted to read this part," Michaels said, peering down at the document. "To get Detroit-style on the map and as well recognized as Chicago style and New York style pizzas throughout the world."

Michaels swiveled in her chair to return the statement to its proper place on the shelf. "And he's done it," she said. "He's done it."

omccarthy@detroitnews.com

©2025 The Detroit News. Visit detroitnews.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC. ©2025 www.detroitnews.com. Visit at detroitnews.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments