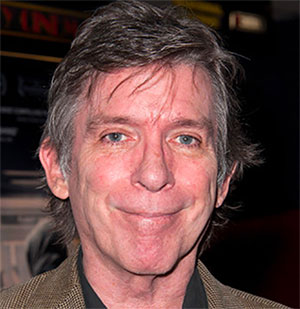

Q&A: Grammy nominee Barrera wants songwriters to get their due

Published in Entertainment News

LOS ANGELES — There is no rest for songwriter Edgar Barrera, who in the weeks leading up to the 68th Grammy Awards in Los Angeles finds himself hopping around northern Mexico doing what he does best — penning your favorite artist’s songs.

“Right now I have some writing sessions [in Monterrey] for Fuerza Regida’s new album, two days from now I start Carin León’s new album, then I go to L.A. for the Grammy Week,” Barrera said through Zoom, having freshly arrived from Tulum.

Bopping to and from recording studios is exactly the type of lifestyle Barrera always dreamed up. Raised between Roma, Texas, and Miguel Alemán, Mexico, the lyricist had musical aspirations that led him to Miami, where he learned to compose songs across the Latin music spectrum — pop, urban, reggaeton, bachata and vallenato.

In recent years, Barrera has been instrumental in shaping the sound of música Mexicana, working closely alongside the biggest acts in the genre, including Grupo Frontera, Peso Pluma, Neton Vega and Fuerza Regida.

At the time of our call, Barrera had learned that his song “7-3” with Peso Pluma and Tito Double P — a sharp corrido riddled with double entendres about a sneaky link — had just cracked into Spotify’s Top Global 50 chart.

“It’s gratifying to see the results — it keeps me going,” said the songwriter, who counts the likes of Bad Bunny, Karol G, Shakira, Maluma and Carlos Santana as collaborators, along with English-language giants like Ariana Grande and Madonna.

With 84 career Latin Grammy nominations and 29 wins, Barrera is tied with Calle 13’s Residente for the most-awarded individual in Latin Grammy history. But mainstream recognition of his contributions to the music world has come at a different pace.

For a third year in a row, Barrera is nominated for songwriter of the year at the Grammy Awards. Although he has yet to win, he is the only Spanish-language composer ever to be recognized in this category.

“I’m competing with the best of the best in the game. For me it’s already a huge honor to just be there representing the Latin community,” he said.

Throughout our conversation, Barrera shared insights about the future of música Mexicana, music award shows and his belief that songwriters must be respected for their artistic contributions.

[This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.]

Q: How do you make sense of being the only Spanish-language songwriter nominated in this Grammy Awards category?

A: It’s important for stuff like this to happen because I’m opening the door for future generations. I come from a small town where songwriting is not even considered [a career]. When I would tell my friends I wanted to become a songwriter, they were like, “Do they even pay songwriters?” There’s a lot of misinformation out there.

For me, the most important thing is opening the door for them to have possibilities. That’s already a win.

Q: Tell me more about that moment you decided to move to Miami.

A: I come from a family of musicians. My dad is a musician and my mom spent all her life raising kids.

For my dad, he had gone through it already. He’s part of a band called Mr. Chivo. They play grupero music, so my dad knows the process of being a songwriter and my family understood. I have an uncle that also started writing songs and he got some placements with major albums. I would see his name credited as a writer and I always visualized that someday I wanted to be in the back cover of an album. That had always been my dream. Trying to follow that dream was a long process because I was studying electrical engineering, which had nothing to do with music. I wasn’t enjoying it. It wasn’t something that I was having fun with, and I wasn’t doing that good.

I took a class on classical guitar. The teacher told me I had potential for majoring in music, and he was the one that pushed me, professor Kurt at the University of Texas-Pan American. He encouraged me to audition at Berklee College of Music in Boston. I got into the university and they gave me a small scholarship, which wasn’t enough money. My family pushed me to [consider] the possibility of doing an internship to see if it was worth going into this huge school debt. I found a studio in Miami through Facebook, and I just messaged the guy and he opened the door for me to be an intern at his place. And that’s how it all started.

Q: Where do you draw inspiration from when it comes to your music?

A: I think inspiration comes from wherever. A song can lead to another. Every time I’m writing a song, I come up with an idea that might not fit so I’ll write it down.

I channel the artist a lot. After seeing what they’re going through in their personal life, I sit down and start writing ideas. I do a lot of co-writes in my music. I try to get the artist involved with the creative process.

Like today, I’m going to be writing with another writer and he might be going through something. Or I might just come up with an idea of something that I read earlier today. I do read a lot. If I’m not doing physical books, I do audio books, so I keep myself busy all the time. I listen a lot. That’s the key to being a good guitar writer, is learning how to listen.

Q: You’ve helped various música M exicana stars take off. Where do you see the genre as a whole headed?

A: The genre had really big moments years ago where it really exploded. It was the biggest thing when Grupo Frontera came out, Peso Pluma, Natanael Cano — it was like a back-to-back situation where you would see a Mexican song being No. 1 globally on Spotify or Apple Music.

I remember when we did the song “Un X100to” with Bad Bunny [and Grupo Frontera], that was the first time that a song was No. 1 all over the place. People would tell me, “You guys are creating something special.” [But] that’s been our Norteño sound for like 40-50 years now. We’re not reinventing the wheel.

It’s the same beat as a Ramon Ayala song, or an Intocable song that would play in the ‘90s.

I think it was the right moment for the music to be globally recognized. As a side note, when I got to Miami, it was really hard for me to fit into the culture because I was the Mexican kid between this shock of cultures of Puerto Ricans, Colombians and Venezuelans that had reggaeton culture through their veins. But I was never afraid to be myself. I’ve never been embarrassed of who I am and where I come from.

I remember when I started working with artists like Christian Nodal, those first albums were fully done in mariachi, and we brought mariachi to the younger generations. It’s always been my personal goal to bring all those genres back to the newer generation so that they don’t get lost in translation.

Q: The Latin Grammys have received some criticism in years prior for their exclusion of música Mexicana in the major categories — yet you’re someone who’s been at the forefront of this award show as the most nominated individual. How do you reconcile those two?

A: One of the main reasons why artists don’t get nominated is because they don’t register themselves. Most of those artists are independent artists and they don’t know the process of getting nominated for a Grammy. Most artists think it just happens overnight.

The label has to register the product. The artist has to be a voting member of the Latin Recording Academy. It’s a whole process. It’s about educating them because 90% of them are independent artists. They run their own labels, which is also a big mess whenever it comes to paying out royalties. Being independent is cool for the artist, but it’s not cool for the people that work with the artist because you have to rely on them to pay out royalties on time, or pay out whatever is due to the writer or the producer.

Now that I’ve been more involved, you’re starting to see artists [get recognized]. Grupo Frontera won a Latin Grammy last year. Carin León won an American Grammy last year, too.

Q: You have your own label, Borderkid Records. Why was it important for you to create something of your own?

A: I want to support acts that are starting off. My label is different. I’ve always said that I don’t sign people to the label. I teach them how to be their own master owners. For example, I got some kids that are part of my publishing company, but I don’t sign them as publishing. I don’t steal from them. I try to educate them and teach them how to earn money as songwriters, how to protect [their work].

I do co-own with the writer a small portion of whatever publishing they have, but I don’t do it like the way 99% of the artists out there sign people off, or label sign people off. At the end of the day, I’m a creator, so I try to put myself in those shoes and treat people the way I wanted to be treated when I started out my career.

Q: You bring up being a creator, but are there other reasons why you aim for fairness?

A: I’ve seen so many people get ripped off and so many people that are not supposed to be getting rich off of talented people. It makes you overthink — what’s the purpose of doing music or doing all this creative stuff? The artist is in the room 24/7 most of the time. Sometimes the ones that make the least amount of money are the writers.

If you don’t have a good song, you don’t have a hit, you don’t have a tour and you don’t have sponsors. You have nothing without a good song. And [many in this industry] still try to rip off the writers. I’m still fighting for my rights. It’s important for writers to respect themselves and understand the business and to not sign off their publishing rights to people that are not doing the work.

Q: In an interview with Grupo Frontera, they referred to you as their Rick Rubin. What are your thoughts hearing that comparison?

A: That’s a big name to be compared to, but I feel like Rick Rubin has a vision and whenever I work with an artist, I try to lead them to where I think they’re supposed to be going in their careers.

Most of the time the artist will listen to my advice. With Grupo Frontera, they’re one of the few artists that is super fair in the game — if they don’t write their song, they don’t get any publishing on that. For songwriters, it’s important for you to find that artist that respects you. Because they have a lot of respect for me and that’s something that I appreciate a lot and the reason why they’re my No. 1 priority. They trust my gut instinct. That speaks loudly of the artist that they’re in there for the right reasons, and I’ll continue to be there for them as long as they need me.

Q: If you could go back to the start of your career, what would you tell your younger self?

A: This past Christmas I was looking at old footage videos of myself being a kid — ‘cause I wasn’t the kid that played with Nintendos or soccer. I’ve always been with my guitar since I was 8, 7 years old, writing songs 24/7. I think back and I [realize] I never had a plan B. What I would tell that kid is to keep doing it, everything’s going to be worth it.

One of the videos I was looking at was of the first time I participated in a talent show, when I was in fifth grade and I played “Samba Pa Ti” by Carlos Santana. Fast forward to this past November, I played with Carlos Santana at the Latin Grammys. Life is crazy and for me it was one of the most special moments in my career as a musician or producer or writer. You can just look at my face throughout the whole performance and I’m just smiling from ear to ear.

Music has brought me a lot of enjoyment and satisfaction with a bunch of things. I’m not a person who looks to the sides. I never envy anybody. I don’t compare myself to anybody. The only person I compare myself to is my younger self. I’m trying to do stuff now to feed my own soul and do projects like Carlos Santana’s new album. I’m trying to do more music for my soul. That’s the whole purpose of 2026. Just like doing stuff that the 15- or 10-year-old Edgar would dream of doing and keep on, keep on dreaming.

------------

©2026 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments