Miami exhibit highlights how Cuba helped create the blueprint for the telenovela

Published in Entertainment News

MIAMI — Before the Cuban Revolution scattered a generation of writers, producers and performers to new creative hubs across Latin America, the island was busy building the blueprint for what would become the modern telenovela.

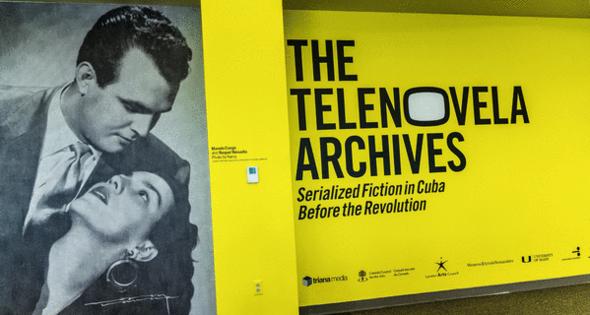

“The Telenovela Archives: Serialized Fiction in Cuba Before the Revolution,” an exhibit on display at the University of Miami’s Cuban Heritage Collection, revisits that formative era through photographs and artifacts from the island’s broadcasting heyday in the 1940s to the ‘60s.

Cuba’s role as an early pioneer of radionovelas and telenovelas — Spanish language soap operas — created a Hollywood-style star system of its own. Large-format photos and original materials from those prolific decades show a country that became a magnet for creative talent from across Latin America and for Spanish émigrés fleeing the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War.

Black-and-white studio portraits by the mononymous photographers Narcy and Armand — Cuba’s most prominent from the ‘40s through ‘60s — line the walls of the exhibit. Nearby are brochures and postcards, sometimes signed, featuring the faces of actors who became household names. Sold at kiosks or handed out to fans, they underscore how the industry spilled beyond sound and screen into print. Many of the items, donated by artists’ relatives or collected by the Cuban Heritage Collection over the years, also include images from major TV networks of the time, such as CMQ.

The show highlights Caridad Bravo Adams, the Mexico-born writer who became a powerhouse of Cuban radionovelas beginning in the 1940s. She ran “La novela del aire,” starting with adaptations of literary classics before moving on to original works like “Corazón salvaje” and “La mentira.” The exhibition also highlights writer Félix B. Caignet, creator of perhaps the most famous radionovela and later telenovela of all: “El derecho de nacer” (1948). Gabriel García Márquez credited Caignet as an early influence.

The melodramas that would come to define the genre — built around class divides, extreme plot twists and characters who remain impeccably styled even in an operating room — took root on the island. The telenovela is woven into Latin America’s cultural fabric and its origins begin in Cuba. Venezuelan documentary filmmaker Juan Andrés Bello, who curated the exhibition with University of Western Ontario professor Constanza Burucúa, points to a lesser-known influence: the lectores who read aloud to cigar-factory workers.

“Oral reading existed in Cuba and in Florida in the tobacco factories, where workers were read to while they worked. The telenovela feeds on that tradition,” Bello says.

The rise of the radionovela in Cuba

One of the most produced telenovelas in Latin America premiered on CMQ Radio in Havana in 1948: “El derecho de nacer “ (”The Right to Be Born”). The exhibit pays tribute to the original protagonists, Carlos Badías and María Valero.

Valero, who came to Cuba in 1939 after serving as a nurse in the Spanish Civil War on the Republican side, became the island’s most important radionovela star. She died tragically in a car accident in Havana and was replaced in the role of Isabel Cristina in “El derecho de nacer” by actress Minín Bujones, who is also featured in the exhibit.

“El derecho de nacer” would eventually become one of the most produced telenovelas, with each generation being introduced to the story by a new crop of actors. The telenovela, however, lost steam as modern audiences began to bristle at the use of a white actress in blackface for the character Mamá Dolores.

Another large poster shows radionovela stars Raquel Revuelta and Manolo Coego promoting their daily 1:15 p.m. show on Radio Progreso. The two, captured in their youthful prime, couldn’t have foreseen how the 1959 revolution would split their paths — and sometimes place them on opposite sides.

“The revolution broke families and friendships. Those who left had to rebuild their careers elsewhere — some succeeded, others struggled,” said Bello, who now lives in exile in Canada.

Coego, often called the “Marlon Brando of Cuba,” went on to star in “Yo compro esa mujer,” “El secreto” and “Raquel.” He died in Miami in 2017.

Revuelta, who co-founded the influential Teatro Estudio with her brother Vicente, became a leading figure of post-revolutionary cinema, notably starring in Humberto Solás’ 1968 classic “Lucía.” She died in Havana in 2004, honored by nearly every major cultural institution on the island.

Television arrives in Cuba

In another corner of the exhibition, CMQ’s mobile unit appears to float against a New York skyline — a 1950 snapshot taken before the equipment was shipped to Cuba. The image captures a pivotal moment, when the island began importing U.S. technology as it quickly became a regional pioneer in television.

Bello says Cuba’s location helped speed that development. He cites the 1952 coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, the first to be televised. The broadcast was filmed in London, rushed to the United States to air quickly thanks to the time difference, then copied in New York and flown to Havana — translated and on Cuban TV almost immediately.

Radio and television also helped expand another thriving pre-Castro industry: advertising.

A 1955 Sylvania ad on display promises, “Your current television could be 7 times better.” Another image shows Félix B. Caignet seated beside a Delco radio, promoting the brand — a reminder that media figures were paid not only for their work but also for endorsements.

The glamorous actress Carmen Pujols appears in a Camay soap ad calling it “the soap of the stars.” Pujols starred in numerous productions and is fondly remembered for portraying the beloved children’s characters, Tía Tata Cuentacuentos.

Gina Cabrera is one of the exhibition’s most frequently featured actresses. She appears with leading man Alberto González Rubio — another pair split by the political upheaval that reshaped Cuban lives. Cabrera remained on the island, while González Rubio eventually settled in Miami, reinventing himself as a radio announcer for Voice of America.

The telenovela in exile

The exhibit ends with the early years of the revolution, when creative radio and television programming would be replaced with broadcasts of Castro’s famously long speeches.

After the state seized all media outlets, exile became the only viable option for many in the industry — a loss for Cuba but a gain for the countries that received a generation of talent. At the end of the exhibition, a map shows the migration of telenovelas from Cuba to Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Venezuela and Puerto Rico. Talented Cuban writers like Gloria Magadan and Delia Fiallo ended up selling their telenovelas in Brazil, Venezuela and Mexico.

Amanda T. Moreno-Schroeder, director of the Cuban Heritage Collection at the University of Miami, says the exhibition brings that legacy into focus.

“Through clippings, photos and recordings, it shows how these media reflected and exported the Cuban popular imagination to other Latin American countries, revealing a legacy that until now remained behind the scenes. By preserving these materials, we safeguard our culture and, at the same time, activate it for educational purposes,” she said.

———

“The Telenovela Archives: Serialized Fiction in Cuba Before the Revolution” is on view through August 2026 at the Cuban Heritage Collection, Roberto C. Goizueta Pavilion, second floor of the Otto G. Richter Library at the University of Miami, 1300 Memorial Drive, Coral Gables.

———

©2025 Miami Herald. Visit miamiherald.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments