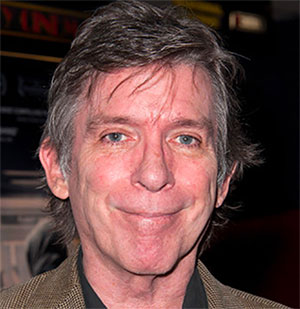

Appreciation: Diane Keaton showed us how to dress up our insecurities and be kooky with confidence

Published in Entertainment News

LOS ANGELES — When Diane Keaton was 11, her father told her she was growing into a pretty young woman and someday, a boy would make her happy. She was horrified. One boy? Keaton — then going by her birth name of Diane Hall — needed to be loved by everyone. It was an early sign that she was meant to be an actor.

“Intimacy meant only one person loved you, not thousands, not millions,” Keaton wrote decades later in her 2011 memoir “Then Again.” Like drinking and smoking, she added, intimacy should be handled with caution.

“I wanted to be Warren Beatty, not date him,” Keaton confessed, romancing fellow artists as long as their relationship was mutually stimulating and then after that, remaining friends. “I collect men,” she jokingly told me when I interviewed her a decade ago, referring to a photo wall in her Los Angeles home of fellows she admired, including Morgan Freeman, Abraham Lincoln, Gary Cooper and John Wayne. She wanted an excuse to add Ryan Gosling and Channing Tatum, so I suggested a love-triangle comedy as a twofer. “No! Not one movie!” Keaton exclaimed. “I want to keep my career going.”

Millions of us did fall in love with Keaton, just as she hoped. She captivated us for over 50 years, from awards heavy-hitters to a late-career string of hangout comedies that weren’t about anything more than the joy of spending time with Diane Keaton, or in the case of her 2022 body swap movie “Mack & Rita,” the thrill of becoming Diane Keaton.

In her final films, including “Summer Camp” and the “Book Club” franchise, Keaton pretty much only played variations of herself, providing reason enough to watch. I looked forward to the moment her character fully embraced looking like Diane Keaton, writing in my otherwise middling review of “Mack & Rita” that the sequence in which she “picks up a kooky blazer and wide belt is presented with the anticipation of Bruce Wayne reaching for his cowl.”

I wanted to be Diane Keaton, even if she wanted to be Warren Beatty.

The contradiction of her career is that the things we in the audience loved about her — the breezy humor, the self-deprecating charm, the iconic threads — were Keaton’s attempts to mask her own insecurities. She struggled to love herself. Even after success, Keaton remained iffy about her looks, her talent and her achievements. In interviews, she openly admitted to feeling inadequate in her signature halting, circular stammers. That is, when she’d consent to be interviewed at all, which in the first decade of her career was so rare that Keaton, loping across Central Park in baggy pants to the white-on-white apartment where she lived alone, was essentially a movie star Sasquatch.

Journalists described her as a modern Garbo. “Her habit is to clutch privacy about her like a shawl,” Time Magazine wrote in 1977, the year that “Annie Hall” and “Looking for Mr. Goodbar” established Keaton as a kooky sweetheart with serious range. I love that simile because she did referr to her wardrobe as an “impenetrable fortress.” The more bizarre the ensemble — jackets over skirts over pants over boots — the less anyone would notice the person wearing it.

Odd ducks like myself adored the whole package, including her relatable candor. She showed us how to charge through the world with aplomb, even when you’re nervous as heck.

Once young Keaton decided she wanted to perform, she set about auditioning for everything from the church choir and the cheerleading squad to the class play. But her school had a traditionally beautiful ingenue who landed the leads. This was Orange County, after all. Keaton would go home, stare at the mirror and feel disappointed by her reflection. She dreamed of looking like perky, platinum blond Doris Day. Instead, she saw a miniature Amelia Earhart. (She’d eventually get a Golden Globe nomination for playing Earhart on television in 1994.)

Keaton stuck a clothespin on the tip of her nose to make it smaller, and acted the part of an extrovert: big laugh, big hair and, when she stopped liking her hair, big hats. By age 15, she was assembling the bold, black and white wardrobe she’d wear forever and her taste for monochrome clothes was already so entrenched that she wrote Judy Garland a fan letter wondering why Dorothy had to leave Kansas for garish Oz. She might have been the only person to ever ask that question.

Not too long after that, Keaton flew across the country to New York where several things happened in short succession that would have puffed up anyone else’s ego. The drama coach Sanford Meisner gave her his blessing. The Broadway hit “Hair” gave her the main part (and agreed she could stay fully clothed). And “The Godfather,” the No. 1 box office hit of 1972, plucked Keaton from stage obscurity to give the fledgling screen actor its crucial final shot, a close-up.

Keaton made $6,000 for “The Godfather,” less than a quarter of her salary for the national deodorant commercial she’d shot a year earlier. Her memories from the set of the first film were uncharacteristically terse. Her wig was heavy, her part was “background music” and the one time Marlon Brando spoke to her, he said, “Nice tits.”

Nevertheless, Keaton’s Kay is so soft, friendly and assured when she first meets the Corleone clan at a wedding, sweetly refusing to let her boyfriend Michael dodge how the family knows the pop singer Johnny Fontane, that it’s heartbreaking (and impressive) to watch her become smaller and harder across her few scenes. But Keaton says she never saw the finished movie. “I couldn’t stand looking at myself,” she wrote in “Then Again.”

Woody Allen put the Keaton he adored front and center when he wrote “Annie Hall.” He wanted audiences to fall in love with the singular daffiness of his former girlfriend and it worked like gangbusters. It’s my favorite of his movies and my favorite of hers, and there’s just no use in pretending otherwise, as obvious of a pick as it is. Even now that I know the Annie Hall I worship is a shy woman putting on a show of being herself, the “la-di-dah” confidence she projects makes her the most precious of screen presences: the icon who feels like friend.

But I also wonder if Allen also made “Annie Hall” so that Diane Keaton could fall in love with Diane Keaton just as he had. Maybe if she saw herself through his eyes, it could convince her that she really was sexy, sparkling and hilarious. But Keaton only watched “Annie Hall” once, in an ordinary theater well after it opened, and she found the experience of staring at herself miserable. She never absorbed her lead actress Oscar win. “I knew I didn’t deserve it,” she said. “I’d won an Academy Award for playing an affable version of myself.”

Nearly herself, that is. The onscreen version of Keaton is stumped when Alvy Singer brings her a copy of the philosophical tome “Death and Western Thought.” But a decade later, Keaton directed “Heaven,” an entire documentary about the subject, in which she asked street preachers and Don King and her 94-year-old grandmother how they imagined the afterlife. (As in Allen’s movie, her grandmother actually was named Grammy Hall.)

“Heaven” is an experimental film that’s heavy on dramatic shadows and surreal old movie footage, the sort of thing that would play best on an art gallery wall. It flopped, as test screenings warned it would, cautioning Keaton that her directorial debut only appealed to female weirdos — people like her. Keaton isn’t a voice in the film. Yet, that she made it at all makes every frame feel personal, and you hear her affection for the cadence of her occasionally tongue-tied subjects. Her first interviewee stutters, “Uh, heaven, heaven is, uh, um, let me see.” Exactly how Annie Hall would have put it.

Today more than ever, I’m wishing Keaton had been comfortable turning her camera on herself. I’d have liked to watch her explain where she thinks she’s gone, however adorably flustered the answer. But in her four memoirs, she safely bared all in print, openly confronting her harsh inner critic, her battle with bulimia, and — yes, Alvy — her musings on death.

“I don’t know if I have the courage to stare into the spectacle of the great unknown,” Keaton wrote in 2014’s “Let’s Just Say It Wasn’t Pretty,” sounding as apprehensive as ever. “I don’t know if I will make bold mistakes, go out on a blaze of glory unbroken by my losses, defy complacency, and refuse to face the unknown like the coward I know myself to be.”

At last, a sliver of confidence peeks out. “But I hope so.”

On behalf of her millions of fans, I hope so too.

------------

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments