Q&A: Embeth Davidtz says 'Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight' tells a story she knew well

Published in Entertainment News

ANAHEIM, Calif. — When the cast of “Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight appeared at the Toronto International Film Festival, you could be forgiven for not recognizing Lexi Ventor, who plays the feral 7-year-old Alexandra “Bobo” Fuller in the film adaptation of Fuller’s memoir about growing up as the youngest daughter of white farmers in Rhodesia.

There’s a reason for that, says actress Embeth Davidtz, who wrote and directed the film and also plays Bobo’s mother in the movie.

“Listen, she was cleaned up for that premiere,” Davidtz says on a recent video call. “In real life, if you just let her be, she would run around and have dirty feet.

“It’s one of the reasons I cast her,” she says. “I had met a lot of children who were really refined little girls, and I just needed an authentic, little non-acting creature to play this part.”

In “Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight,” the story of Rhodesia’s transformation from a British colony into the independent nation of Zimbabwe is told through Bobo’s eyes. The character is real thanks to the absence of artifice in Venter’s performance in her first acting role of any kind.

“I’d seen a few actresses, very sweet kids trying but acting,” says Davidtz, who grew up South Africa just a few years prior to the events of the film in neighboring Zimbabwe. “The Facebook post I put out was I need a kid who’s untrained, absolutely never acted before. It was an absolute requirement for me because there’s a way that children act when they’re acting, right?

“I just said I need a barefoot, wild, preferably grubby little carefree child that doesn’t know anything about movies or filming,” she says. “Who closely resembles this wild Bobo that Alexandra Fuller wrote.

“And when I first saw Lexi she wasn’t as grubby as we ended up making her to look like Bobo, but she had a wildness to her and an unself-consciousness. That’s really what it was. Her face was glorious. The camera loved her face. I knew that I wanted a cinematic face. She’s just adorable.”

Where Fuller’s memoir spans several decades, Davidtz narrowed the focus of the story to the few months of 1980 when years of civil war ended with independence for Zimbabwe and the election of Robert Mugabe, one of the leaders of the rebel forces, as Zimbabwe’s first prime minister.

In the lead-up to the election, Bobo watches as the adults in her world fret over the future that approaches. Her mother Nicola, played by Davidtz, struggles with alcoholism and mental illness while her father Tim (Rob van Vuuren) is sent with a militia to fight rebels at the border

Bobo’s closest friend is the family’s nanny and housekeeper Sarah (Zikhona Bali), who loves the girl even as her coworker Jacob (Fumani Shilubana) warns Sarah that she risks being seen as a collaborator with her white employers.

Davidtz, who was born in the United States to South African parents, moved back to that country in 1974 when she was 8 years old; she says she wanted to make a movie of Fuller’s memoir for years, drawn to it by how it mirrored so many moments of her own life.

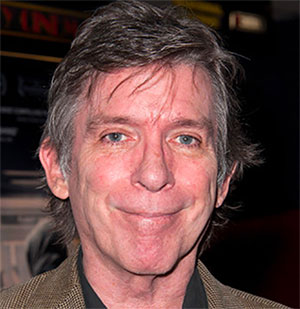

In an interview edited for length and clarity, Davidtz, whose resume includes memorable roles in films such as “Schindler’s List,” “Matilda,” and “The Amazing Spider-Man,” talked about the appeal of the source material, how she accidentally ended up a first-time writer-director, and how the themes of her film remain relevant 45 years after the events it depicts.

Q: How soon after Alexandra’s book was published in 2001 did you come across it?

A: I actually read it right after it came out and I was wowed. Every person that I knew in England and Southern Africa, and even people in America and Australia were like, “Gosh, you’ve got to read this woman’s book. So I read it and I was thunderstruck by how she captured the world, a world that was similar to the world that I grew up in.

But also just the brilliance of her writing. She’s very funny, she’s very exacting. She’s very sort of relentless in what she exposes about herself and her family, but she does it in a loving way.

And more than anything, that character of Bobo. It was like a Scout from “To Kill a Mockingbird” or, oh gosh, the Tatum O’Neal character in “Paper Moon.” And I thought, God, this would just make such a great film.

Cut to years later, I was thinking of what would be an interesting part, something I’d be interested in developing, and I thought of her. And the rights happened to be available.

Q: When was that, and how did you proceed once you had the rights?

A: It was about 2016, 2017. I think I spent a long time on the screenplay. I thought I’d find a writer. I couldn’t find a writer. So I did probably 25, 30 drafts myself, slowly. Because the book is very long. The book spans 20-something years and I just made it about a very short space of time at the end of the war.

Q: Why did cut it down to that moment?

A: Oh my gosh, I stumbled around and I was writing an epic, what would have ended up being a miniseries. Then slowly I realized, the reason I wanted to do it was because I wanted to play the part of Nicola, but as I went along with all my various drafts, I realized, really, the story is Bobo’s story.

The biggest moment of clarity came when I realized, oh no, I have to tell it entirely from the child’s point of view because then I can put in all the racial things I need to. All the prejudice, all of the learned behavior, all of the voice of that kid that was clear in her book.

Q: The point of view let you have Bobo ask adults in her world questions like, “Are we racist? Are we Africans?”

A: Exactly. She can talk about “Africans not having last names.” She can talk about “Don’t be friends with them.”

Q: Had you always intended to write, direct and act? Or did that just kind of happen?

A: It started out as, “I want to play this part, so I’m going to acquire the rights and I’ll find a writer, and then I’ll find a director.” Then as things went along, I couldn’t find a writer, so I wrote it. Then once I’d written it, once I’d gone through my 25 or 30 drafts, I knew it so well that I thought, “How can I hand this over to somebody else?”

I thought, gosh, I know every angle, every frame, everything I want to be in slow motions, everything. I knew what it needed to be. I just thought, I think I know how to do it. I mean, it was a very risky thing to do and very scary. There wasn’t a day I wasn’t terrified. Even while I was editing I was terrified, thinking, who do I think I am doing this?

But I kind of knew on some level instinctively I just know this story in my cells and in my bones. I know how to tell it. So I stuck with it. Then I didn’t really want to act in it anymore. I’d made the part of the mother much smaller and that wasn’t the main thing. The main thing was telling the story.

Q: It’s interesting how you started out not wanting to write or direct and ended up not wanting to act — but then did all three.

A: Yeah, not something I would recommend. [She laughs] It was hard. And in the end, I was the least expensive option, so it was great. I didn’t have to really pay for myself and I could minimize the amount that I had to be on camera.

Q: What was it like directing Lexi, who as you said didn’t know anything at all about acting or filmmaking?

A: In my meetings with her, when I taped her, she was dead keen to light up a cigarette [as the movie has her do] and enjoyed pretending to puff on a cigarette. The way I got her to [deliver her lines] was to have two cameras on her at all times, one very close, one sort of medium. She could say a line the way I told her to say it and then do it a line at a time.

She was very good at even bringing her own expression to things. Sometimes she’d change a sentence. She’d forget a word and say it the wrong way, but the wrong way was the right way. It’s just who she is and a perfect melding of what Alexandra Fuller created, what I wrote and directed, and what she brought to it as a blank canvas as herself that worked.

Q: Is she from a rural part of South Africa? Was she comfortable on location there?

A: As comfortable as a child could be. People at one point said, “Why don’t we look in England?” I said there’s no English child that can run around barefoot in the wild with her dog. That was her dog. I always had her dog in scenes with her.

I said, Don’t brush your hair in the morning and most times her hair wasn’t brushed. So I didn’t have to do anything but I could put dirt on her face. She lives in a small town but she runs around barefoot all the time. She seldom wears shoes so that was easy. It was close to casting to type as I could have found for the character of Bobo.

Q: Zikhona Bali also has a beautiful presence on screen, though she’s much, much quieter and calmer as Sarah than Lexi is as Bobo.

A: Zikhona was a gift to me because, first of all how she worked with Lexi, because Lexi is a lot. I only had three hours a day with her. It’s hard for her to focus and concentrate. And Zikhona was like a glass of cold water. She just would cool things down. She would stabilize Lexi. Again, it was like a lightning bolt, absolutely clear that this was the person to play the part. She’s just wonderful.

Q: You were born and lived in the United States until you were 8 – about the same age as Bobo. What was your experience like moving to South Africa then?

A: I moved from New Jersey, so I had only known lovely green rolling hills and yellow school buses, even though my parents had come from South Africa. So moving at the time we did was incredibly traumatic for me. We were almost immediately in a state of emergency. Soweto riots began. There were always police in this sort of military state.

So my very gentle sort of American childhood was kind of ripped apart when we came to South Africa. Now, my parents were oblivious. Differently to how the Fullers are oblivious but my parents were just back in South Africa, living with something that they knew. They didn’t necessarily agree with it but they didn’t do much to make it OK for us.

That’s why I think I’m so obsessed with telling a story from a child’s point of view. Because that moment in time, exactly the age of Bobo, really resonates for me as a difficult time and a very scary time. All of that stuck with me so that when I read Alexandra’s book I so recognized what she described as the terror of being a kid. It doesn’t leave us. It’s in there. So when I got to tell the story I feel in some way I got to exorcise the stuff that I’d always felt and kept inside.

Q: It’s 45 years since the events depicted in the film. How do you hope the film will speak to today’s times?

A: There’s a twofold thing I’d say. One is, you know, people should know when they look at African countries and form conclusions about them and the way that things are done there, that the African countries inherited what was handed to them after colonialism. It’s sort of what Sarah represents and what I was trying to show at the end of the film. That there’s this beautiful elevated character to the Indigenous people of Zimbabwe, of South Africa.

So I would want people to look at that and know that’s there, and read about it and learn about it. I think that there’s nobility in trying to fix the mess that they were handed after colonialism ended.

Then the other thing I’d say is for people to look around the world at the wars that are going on everywhere, and everywhere there are children watching. So Bobo’s experience of being in the middle of not only a family coming undone on the inside, but a world outside of violence is everything we see on the news every day.

There are the Bobos of the world watching and living through it. You know, we don’t learn, but it would be nice if we did. If it stopped somehow.

©2025 MediaNews Group, Inc. Visit ocregister.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments