International student enrollment declines at nearly 2 dozen Illinois universities

Published in News & Features

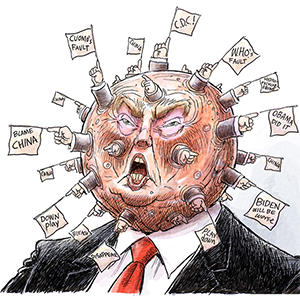

CHICAGO — International enrollment dropped at nearly two dozen Illinois universities this fall, with some seeing dramatic declines after the Trump administration tightened student visa policies.

A Tribune analysis of 27 of the state’s largest universities found that foreign enrollment dipped at all but four institutions, including the University of Chicago and a handful of liberal arts colleges.

The data shows the sweeping scope of President Donald Trump’s efforts to reshape higher education: While the decline in international enrollment hit large, urban schools such as DePaul University, it also reached rural colleges downstate, enrolling just a few thousand students.

Many institutions are feeling the pinch. DePaul, which saw a 62% drop in new international graduate students, announced a string of budget cuts last month. Lewis University, which saw a 37% drop in foreign students, is cutting dozens of staff positions.

“We accept a large number of domestic students, as well as a large number of international students. One does not replace the other,” said Lewis Provost Christopher Sindt. “When we lose international (students), we essentially lose total enrollment for the institution.”

Experts have been warning of the downturn for months, as Trump pursued a string of policies curbing the flow of students from abroad. That includes a travel ban targeting 19 countries, a temporary pause on visa interviews and new social media screening. He even directly pressed some schools to cap international enrollment.

The decline threatens the bottom line for many universities, who rely on international recruitment for a revenue boost. It’s also a major hit to the U.S. economy. Foreign students’ economic contributions fell by $1.1 billion this fall, costing the country nearly 23,000 jobs, according to NAFSA: Association of International Educators.

For schools that pride themselves on being diverse, global institutions, the decline may jolt campus culture, experts say. A recent study from the Institute of International Education found that new international enrollments plummeted 17% this fall compared with the year prior.

“International students have been a huge, net positive gain for the nation,” said Mitchell Chang, a professor of education and former provost at the University of California Los Angeles. “We’re going to feel it, for sure.”

Illinois universities collectively lost thousands of international students, according to the Tribune’s analysis. Regional schools bore the brunt of the decline. Eastern Illinois and Western Illinois universities saw their foreign populations plummet 51% and 40%, respectively, the largest shares across the state.

Five schools bucked the trend. The University of Chicago saw the most notable growth, reporting a jump of 163 international students this fall. Wheaton College also saw an increase of about 14%.

It’s not a surprise to experts. Elite universities, with global prestige and large applicant pools, were expected to be more insulated from the decline. Liberal arts colleges, meanwhile, tend to be undergraduate focused, and most students from abroad are pursuing graduate degrees.

“I think overall, there was a sense that the larger, more well-recognized schools would be able to weather some of these choppy waters, more so than smaller, regional, perhaps less well-known schools,” said Rachel Banks, senior director for public policy and legislative strategy at NAFSA.

Some schools were able to bridge the gap. Chicago State University, for example, saw a 31% drop in international enrollment but welcomed its largest freshman class in a decade. As did Northern Illinois University, which lost 19% of its international students. The University of Illinois System set a fall enrollment record.

For other schools, though, the trend has compounded a looming demographic cliff.

“If these are permanent shifts, that would pretty much be the end of international programs as we know it,” said Randy Glean, associate vice president at WIU’s Center for Global Studies.

At Augustana College, a small, liberal arts school in Rock Island, international enrollment held steady from the previous fall. It’s the payoff of years of overseas recruitment, which has increased foreign enrollment eightfold since 2012. International students now represent 20% of campus.

“I’ve got two full-time people who travel the globe to recruit international students, and this fall, they’ve been anywhere from Pakistan to Rwanda to Kenya to Mongolia,” said Kent Barnds, executive vice president for strategy and innovation.

But it’s not all smooth sailing. New international enrollment dipped slightly, even amid Augustana’s aggressive recruitment efforts. Many students aren’t sure if they’ll be able to obtain a visa, or if it’s still worth it to study in the U.S. That could jeopardize the school’s future enrollment prospects.

“We are certainly hearing from international students, as well as agents who represent us abroad, that there are reservations about studying in the U.S.,” Barnds said. “That does have us concerned.”

In restricting foreign students, Trump has cited national security issues and the need to reduce competition for admissions slots. In April, his administration abruptly revoked and later restored the visas of more than 1,000 international students across the country.

This fall, the president also announced a new $100,000 fee for H-1B visas, the primary employment pathway for foreign professionals. The move was an abrupt overhaul of a 30-year program that steadily built up the country’s research landscape. At Northwestern University, for example, the majority of post-doctoral researchers are from overseas.

“For decades, we’ve drawn the best and brightest all over the world to come to the U.S.,” said Chang. “On that level, it’s been a brain gain for the U.S.”

And the decline might get worse. The Institute of International Education found that the total number of students, nationwide, only dipped 1%. Many schools were able to offset their losses with their existing international enrollment. But as the pipeline of new students dries up, more universities and local economies could feel the strain.

“Even small businesses in a college community can be affected by that swing, with fewer people being attracted to the community,” Banks said. “It can really shake itself out in a day-to-day way.”

A spokesperson for Northwestern, which last year enrolled close to 5,000 international students, said specific data was not yet available. But last fall, foreign enrollment accounted for 13% of the student body, compared to 12% this year, according to the school’s website.

Illinois Institute of Technology, one of the nation’s universities most reliant on international students, did not respond to repeated requests for comment. Still, their website shows that foreign students represent 60% of graduate students — compared to 71% last fall.

____

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments