'A whole new outlook on life': These KY groups help people not return to prison

Published in News & Features

LEXINGTON, Ky. -- Cathy Stewart was imprisoned at the state and local level for a drunk driving crash she caused that severely injured a man and his son in 2018.

The 47-year-old was previously in and out of rehab, on the run and pregnant before she ended up in the Franklin County Detention Center.

She held her young daughter for the first time inside the facility as part of a Wanda Joyce Robinson Foundation program. It was the only time during her five-and-a-half years behind bars she touched her baby. When she was transferred to prison, the COVID-19 pandemic shut down all in-person visitation.

“It’s just as important for the kids and the mothers to get help,” Stewart said. “It was the only time in five-and-a-half years that I got to see her, and it was the only connection I had with my kids.”

The Wanda Joyce Robinson Foundation is one of Kentucky’s many organizations striving to prevent people from returning to prison.

Across the commonwealth, public governments, private groups and nonprofits are joining efforts to achieve one thing: Help inmates stay out of prison after they’ve done their time. They want to offer new skills and new opportunities that lead to new lives.

By working to restore relationships between incarcerated Kentuckians and their families, and connecting them to resources even before they reenter society, the groups are trying to drive down the state’s rate of repeat offenders.

The Wanda Joyce Robinson Foundation helps parents in jail maintain family ties. It allowed Stewart to give Christmas gifts to her older children while she faced 20 years in prison and went up for parole three times.

Stewart’s goal was to get the most out of programming before her release in 2023. Stewart was confronted with sobering statistics about the low chances she had to make something of her life after prison.

“I thought, ‘This is not going to be my life, and this is not the end,’” she said.

“‘I am not going to be pitiful. I want to beat this and come out above this because there has to be a way.’”

Family reunification, financial literacy, youth violence prevention and workforce development programs have kept formerly incarcerated Kentuckians, like Stewart, out of prison. It’s even inspired those enrolled in programs to give back to the nonprofits that helped them.

Since 2022, of the nearly 13,000 people released from state custody, 8,930 have not returned, according to the state’s Justice and Public Safety Cabinet. Nearly 70% of people released over the past two years have not returned to prison.

Determining a national rate of reincarceration is challenging due to the wide range in reporting from the states.

In 2008, the Bureau of Justice Statistics examined a cohort of people released in 24 states and found 66% of them were re-arrested within three years, 48% had an arrest that led to a conviction and 49% returned to prison.

For Kentucky inmates, the recidivism rate, or percentage of those who relapse into criminal behavior after being imprisoned for a previous crime, is 30.8%, two percentage points lower than in 2021.

In 2020, Kentucky recorded its lowest recidivism rate at 27.2%.

On average, Kentucky invests about $5 million per year in state funds supplemented by federal grants on expanding and improving reentry services. Each of Kentucky’s 14 state prisons have reentry centers and last October, an executive order established the Governor’s Council of Second Chance Employers to promote second-chance hiring.

A low recidivism rate is crucial for states to achieve since nearly 95% of the state’s jail population will be released, and it’s costly to keep them there. In 2015, the state spent an average of $16,680 per inmate, according to the Vera Institute of Justice.

Founded in 1961, the Vera Institute is a national, nonprofit research and policy organization focused on reforming criminal justice and immigration systems.

“Thousands of people will be released from prison every year, and by investing in their success, our children are safer, our communities are stronger and taxpayers’ money is saved,” said Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear.

“Kentucky is a place where people can realize their hopes and dreams, and we are working to ensure that is true for every one of our citizens.”

Family reunification

Based in Frankfort, the Wanda Joyce Foundation was founded in 2018 and named after the mother of co-founder Dale Robinson. The non-profit serves children and families through mentorship and community.

Amy Snow, director of the foundation, said people often think of reentry as such tangible items as a driver’s license or finding a place to live. Yes, it’s those things, she said. But reentry often goes well beyond those basic needs.

Building relationships, for instance, is essential. That’s because it helps those coming out of prison create a new sense of self, different from who they were before prison.

“We are looking forward to seeing the families that are in this program building their relationship and having that foundation for when the parent is returned to the community,” Snow said. “It is about building relationships with people, and maybe they are just starting with their kids, or their family who are in jail.”

Fifteen percent of Kentucky’s kids have had an incarcerated parent — a rate two times higher than the national average and the highest percentage in the nation.

More than 60% of incarcerated women are mothers. Their children, according to an Annie E. Casey Foundation study, are five times more likely to enter foster care than if their father was incarcerated.

Based in Baltimore, the Casey Foundation is a private, national foundation that formed in 1948 to improve the lives of children and families facing poverty and disadvantage.

Those who keep contact with their families while doing time have one less barrier to navigate once released. When a mother is reunited with her family, a George Mason University study found they are less likely to return to prison and more likely to have secure employment opportunities and health care for substance abuse disorders.

Starting a new career behind bars

When she was released in 2023, Stewart had nothing but the clothes she was wearing when she arrived at the jail and a newfound direction – she was going to help incarcerated women. While waiting for her driver’s license to be reinstated, she took rides to find work in Frankfort.

“My past hurt people’s lives, directly or indirectly. My recovery is directly or indirectly helping people,” Stewart said. “I have a whole new outlook on life. I am sorry for what I did. The only way I can make up for it is by trying to do something right.”

Now, Stewart is the first in Kentucky to provide peer support specialist certification classes at the Franklin County Regional Jail.

Previously with only a ninth-grade education and later a GED, she’s now enrolled in college classes on her way to becoming a social worker.

And Stewart is an office assistant at the Wanda Joyce Robinson Foundation, the same organization that gave her the opportunity to connect with her family while behind bars.

Others have thrived through job opportunities that were available in prisons and jails.

Manuel Patton, 51, designed his own clothing brand while serving a 15-year federal sentence for drug and firearms charges.

While incarcerated, Patton worked with UNICOR, a government corporation operating prison industry programs, designing patents when a vision came to him to start his own clothing line in December 2015.

He worked from 7 a.m. until 3:30 p.m. in the federal prison and spent the rest of his time in the law library or in his cell designing clothes. He spoke with his family over the phone to trademark his business: Life is No Rehearsal.

Shortly after release in 2021, his logo was trademarked. He sells clothes he’s designed out of the trunk of his car, works at the University of Kentucky and is a licensed painter.

On every piece of clothing he sells, a card on the inside tells his story: “Do the best to make the best decision with your life every day because we only get to come through here one time, there are NO DO-OVERS.”

Financial literacy over fear

Patton said a mindset change was essential to shedding his previous life and starting anew after prison. He also credits being on home incarceration as a way he was better able to integrate into society.

“Mindset is everything,” he said.

“The people that you hang around means everything. If you are on something different, and your friends are on something different, you have to want something better for your life.

“When you change your mindset, everything changes.”

Patton said Dale Morgan, a Lexington financial analyst who speaks to men in prison, helped him get his finances in order. Morgan said mindset is a major hurdle he sees inmates struggling to overcome.

But so is fear.

“They are scared about how they are going to be able to adjust when they come out of prison,” Morgan said. “They’ve got three kids and the wife needs this – how are they going to support them? Some have programs, and some are released to figure it out. Those are the ones who get returned to prison life.”

The state releases more than 300,000 people from state and local jails combined each year. About 33% of individuals released in 2010 remained jobless four years post-release, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

Limited assets, restricted public benefits and system underfunding can perpetuate poverty and recidivism risk.

Workforce development: New economic opportunities

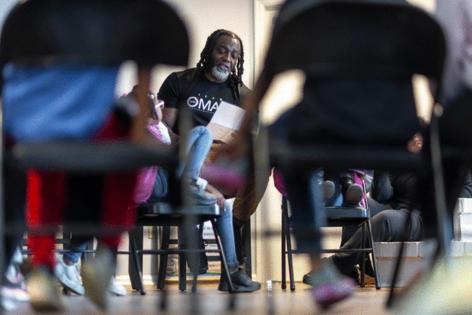

In Lexington, a job training and social reintegration program is giving inmates at the Fayette County Detention Center another opportunity.

This summer, Second Chance Academy began its third year running a seven-week life and career readiness course.

Led by local nonprofit Jubilee Jobs in partnership with the city and the county detention center, program applicants spend an hour each week with reentry coordinators learning and putting those lessons into practice.

By the end, participants have built a new resume and tried out different workplace simulations on a virtual reality headset. Other sessions during the course teach skills in interviewing, conflict resolution and parenting.

Second Chance Academy was Lexington’s Director of Business Engagement Amy Glasscock’s first project when she moved to working for city government in April 2023 after almost two decades in workforce services at the Bluegrass Area Development District.

Her job now falls under the city’s economic development department, and it’s sometimes a point of confusion, but she said there can be no economic development without workforce development.

“Sometimes, people can do a job. That’s not the problem. It’s keeping the job and then dealing with all the other things in their life and how to handle those things that help them maintain that employment,” Glasscock said. “So, we really want to work on all those things, as well.”

After release, participants are on the receiving end of more personalized support for at least a year while they look for and hold down a job. In 2024, Jubilee Jobs helped more than 600 people in Fayette County get employed.

Of the academy’s graduates, less than 10% — 13 of 175 — returned to jail or refused to participate in the program after release.

Inmates who get a job while in prison or right after release are 24% less likely to return, according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Among those who keep a job for at least one year after release, only 16% return.

“We’ve never felt like training was just good enough,” said Kevin Atkins, the city of Lexington’s chief development officer. His department’s workforce development partners, he said, are engaged once they can do employment placement, too.

“So, if they’re going to train somebody, you darn well better be able to get them in a job. … The goal obviously, and especially with that program (Second Chance Academy), is that when somebody gets actively engaged in a job, they are less likely to re-offend,” he said.

During the first class at the academy, the women’s cohort went around the room, quietly introducing themselves to one another, sharing through tears why they showed up. “Show us your sincerity and this will work for you,” said Jubilee Jobs Reentry Counselor Todd Stone to the group of about a dozen women.

Scrawled across the back wall of the room is a line from Proverbs. “Where there is no vision, the people perish,” it says in blue script.

“The only reason you want to participate is because you believe that you’re ready for something different, and you believe that having somebody in your corner helping support your journey to reentry is going to actually help you long term,” Mason King, the CEO of Jubilee Jobs, said in an interview with the Herald-Leader.

“If the dollar per hour is the only reason that you’re going to work … eventually it’s not going to be enough,” he said. “You have to have a why beyond the paycheck.”

For a long time, Lashonda said she hasn’t put in the effort to solve the root of problems she’s dealt with.

Her last name, and the last names of other female academy participants, as well as their criminal offenses, have been omitted per the academy’s policy and to protect their privacy.

So far in her life, Lashonda said the path she’s taken hasn’t always led her in the right destination.

“I have to constantly be reminded that I’m somebody,” she said.

Lashonda has ambitions to help others through addiction recovery after release. But, “I can’t pick you up if I’m crawling, too,” she said.

While incarcerated, Lashonda said she’s had to feel pain.

“I’m now me,” she said.

And that person is who showed up to class and who wants something different.

Another participant, Destiny, said she was in class to find out who she wants to be, to figure out what different looks like.

The woman sitting next to her at the Fayette County Detention Center, Chastity, had a similar story.

“I want something different because I am worth it,” Chastity said.

Several participants said their being in the program hinges on a fear of the unknowns that come with being released from prison and trying to start over. Several women said they know what it’s like when things start to slip.

And in explaining why they showed up to class, they said they felt lucky to have an extra helping hand in a second chance.

Another woman, also named Lashonda, said, “This is my time. I’m willing to go a mile to get it.

“And I am so grateful someone got me and said, ‘Come to class.’”

Youth violence prevention

Gerald “Geo” Gibson was serving his third stint inside a Kentucky prison when he decided to make a change.

On New Year’s Eve 1999, a fear of the end of the world at the cusp of new millennia made Gibson ask, “What has my life been to this point?”

He found himself on his knees, vowing to leave a life in and out of prison, gangs and addiction to find purpose. Gibson, 53, and a father of three children, started developing a program to divert young people from violence while in prison.

After his release, he was working at a gas station when a Lexington Police Department Officer stopped in. Gibson was compelled to share the program idea with the officer as he was at the checkout counter.

Operation Make A Change, the program Gibson conceived on the eve of Y2K in prison, is now run as an extension of the Lexington Police Department inside the Charles Young Center in the city’s east end.

The organization provides mentorship, coaching and support to teens and young adults. It enhances their self-awareness skills in order to equip them with the tools to stop problem behavior and make sustainable behavior change.

Well-implemented programs with behavioral and family involvement have continued to produce reductions in national recidivism rates, according to a research study on the crime prevention program New Perspectives.

Youth with delinquent behavior patterns are at risk of developing a chronic criminal career trajectory that can be costly to society and are in need of early preventative care.

For Gibson, the program is meeting youth where they are and when they have a changed mindset, to jump on the opportunity to offer resources.

The program also introduces participants to environments they may not have experienced: Field trips to the arboretum and going on college tours.

In sessions held in Lexington neighborhoods or during after-school clubs, Gibson has the kids share the best thing about their day. If someone is facing a challenge, the group talks through their emotions and potential solutions to the problem.

“I work with a lot of kids right now who are in the court system, in the streets dealing with gangs and drugs, gun violence and stuff like that,” Gibson said.

“I am trying to help them – I can’t change them – but I am trying to advise them and say, ‘Here is my life.’”

In preventative care and other reentry programs, the issues are layered.

Without a job after release, money for rent and bus passes to and from work can be tight, if not impossible. Some former prisoners are in treatment programs, and there are few transitional housing options.

But nonprofit work and investment from local governments has been successful in reducing the state’s recidivism rate so far.

“I’m just really proud of that because there’s a human piece of, ‘Your life matters,’” said King, the CEO of Jubilee Jobs.

“And just because you’ve made mistakes and just because you’ve made bad decisions does not mean that you’re not worthy of a second chance.”

____

Former Herald-Leader news intern Quezia Arruda contributed to the reporting of this story.

____

©2025 Lexington Herald-Leader. Visit at kentucky.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments