Florida DOGE starts hunt for wasteful spending. Will it brandish a machete or wield a pencil?

Published in News & Features

FORT LAUDERDALE, Fla. — Florida DOGE has commenced, delivering hope and glee to some, agita and fear to others.

Day One started small: Nine people dispatched by Gov. Ron DeSantis and Chief Financial Officer Blaise Ingoglia arrived at the Broward County Governmental Center in Fort Lauderdale on Thursday, where a county government aide said they were ensconced in an “undisclosed location.” Another group arrived at Gainesville City Hall.

Little is known about precisely what the DOGE teams are up to. There have been broad declarations from DeSantis and Ingoglia about the effort, but just how they’re going about their business, and the ultimate expectations, are among many unanswered questions.

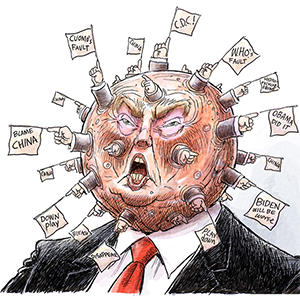

Will the Florida DOGE probe of cities and counties selected by the governor or his aides, and overseen by his office, model itself after its federal namesake — which saw teams overseen by billionaire Elon Musk rampage through agencies eliminating employees, vacuuming up citizens’ personal data, and gutting government programs?

Or will it produce political talking points proving, or at least purporting to show, wasteful or improper spending — and become propaganda for DeSantis to sell his final big attempt to remake the state before he leaves office: eliminating property taxes?

“Nobody knows,” said Steve Geller, a Broward County commissioner who spent two decades in the Florida Legislature, including a term as Senate Democratic leader.

Aubrey Jewett, a University of Central Florida political scientist who has focused heavily on local governments for decades, sees DOGE as a “combination of symbolic and tangible actions.”

“The symbolic part is DOGE is a brand, a part of the larger MAGA movement, and it really fits into what Republicans have pushed for many years as part of their ideology, which is smaller, leaner government and lower taxes,” Jewett said. “And also, for DeSantis in particular in this case, trying to highlight and make the case that there is room to cut property taxes and maybe even to eliminate them.”

State Rep. Chip LaMarca, a Broward Republican and former county commissioner and Lighthouse Point city commissioner, said he thinks DOGE will be a plus.

He doesn’t expect the catastrophe that some in local government fear — or uncover massive problems some government skeptics assume. “Both sides, I think, in some ways will be surprised at what they’ll find.”

Stated purpose

DeSantis and Ingoglia offered two central reasons for why they wanted to DOGE local governments: overspending and questionable spending.

In too many cases, they said local governments’ spending had ballooned faster than it should have, and they wanted to uncover the reasons why.

On the hunt for wasteful or improper spending, DeSantis emphasized so-called diversity, equity and inclusion efforts and any money Broward has spent on the Green New Deal.

National progressives years ago championed the Green New Deal to reshape the economy and energy use in an attempt to deal with global climate change. Broward doesn’t have a Green New Deal, but it has spent money on climate-change-related efforts and programs to increase resilience caused by changes in weather.

Geller said Broward commissioners, even though they’re all Democrats and sometimes disagree with the policies emanating from Republican-controlled state government, follow the law.

DeSantis said the amount of property taxes taken in by Broward County has increased by almost 50% since 2020 while the population has increased less than 5%.

Inflation is a factor contributing to higher government budgets, Ingoglia said.

“Governments really should not be increasing their budgets more than population growth and inflation growth,” Ingoglia said. “Anything over and above that should be looked at.”

In March, after DeSantis had been talking about a Florida DOGE and citing Broward County in appearances around the state, county officials visiting Tallahassee provided the governor’s office with budget information showing the county’s spending growth was “nearly identical” to the combined effects of inflation and population growth.

It cited a 28.9% increase in the consumer price index from fiscal year 2020 to fiscal year 2025 and a 4% increase in population during that time. The combination “yields a cost pressure of +32.9%, nearly identical to the 33.9% total budget growth over the same period.”

Jewett and state Rep. Kelly Skidmore, a Palm Beach County Democrat who is her party’s policy chair in the House, said growth in local spending has often come after voters approved referendums to add to the sales tax in their counties because they wanted the benefits that would come from raising the extra money.

As communities across the state have taken in ever more tax money, they haven’t always spent it wisely, sometimes devoting dollars to visible, flashy projects rather than important, but hidden needs, said state Rep. Mike Caruso, a Palm Beach County Republican.

“Infrastructure is still a mess. You don’t find cities having bold big projects to replace their sewer lines that are 70 or 80 years old. They just continue to repair them as they explode.”

“Counties have been very fortunate in drastic increases in property value over the years, which has increased their tax bases. And I think the general consensus of many in Tallahassee is that they’re not spending those additional tax dollars appropriately or in a way that will help the citizens of Florida,” Caruso said.

Political targets?

The choice of the first two targets, Broward County and the city of Gainesville, aroused suspicions because they’re Democratic bastions in the increasingly Republican state.

Broward has more registered Democrats than any other county in the state and is a place where he received just 42% of the vote when he won reelection in 2022, one of only five counties he lost.

Skidmore said DOGE appears to be an attempt to make “Democratic counties look like spend-and-tax liberals. And that they come in as the savior, in air quotes, to create efficiencies and save taxpayer dollars.

“They’re doing it to keep a stranglehold on their power and to change the Democratic politics of certain counties,” Skidmore said. “Why else did they start in Broward?”

DeSantis said DOGE efforts were “starting with those jurisdictions which have received a lot of complaints for their spending practices.” He also said “I’ve had a lot of complaints from folks down here in South Florida.”

His office didn’t respond to questions about details of any complaints, including how the governor has received them or for examples.

As proof they weren’t focusing just on Democrats, the governor and CEO cited Republican Manatee County, the third stop on their July DOGE announcement tour.

Later, the investigative newsletter Seeking Rents reported more complex politics than what appeared on the surface. “Manatee County has more recently turned against the governor in local elections. It happened a year ago, when five Ron DeSantis-appointed or endorsed candidates were on the Manatee ballot — and all five lost.”

State power

Florida DOGE doesn’t explicitly have the authority to act the way Musk’s acolytes did with Trump’s blessing. But they can make life exceedingly uncomfortable for local elected officials.

Skidmore said she is concerned about DOGE’s potential to create “massive disruption in the guise (of combatting) fraud and abuse. Whether they are correct or not, they don’t care, because that’s not what they’re after.”

LaMarca and Caruso, a certified public accountant who has done forensic accounting work, said DOGE can audit and investigate. But they don’t anticipate demands that local governments take specific actions.

“I don’t think they’re going to come in and do orders to fire people at all. I just don’t see that,” Caruso said, adding that it could have an impact on requests for future state funding. “County commissioners and city commissioners will be called to account for how they’ve misspent taxpayer dollars.”

LaMarca said they would be looking for waste and abuse. “The function of this isn’t to go in and tell the county government how many employees they should have or how they operate,” he said. “They’re not coming in looking to tell Broward County how to run things.”

And Jewett said it doesn’t seem as if the DOGE teams are going in to “create financial havoc and panic, which you often saw at the federal level. There’s definitely some parallels, but it seems as if the state’s going about it not quite as aggressively as what happened at the federal level.”

He said, however, that “it does seem that the way the state is going about it is pretty heavy handed in terms of local control.”

The governor and CFO have had some longstanding authority to ask for and review financial information. But a more express authorization for Florida DOGE was spelled out in one section of a massive piece of legislation passed during the spring legislative session.

The language of the law is broad, authorizing “a review of the functions, procedures, and policies currently in effect” for any local government including “any personnel costs, administrative overhead costs, contracts and subcontracts, programs, grants and subgrants, any outsourcing with a nongovernment organization, and any other expenditures.”

Within seven days of a request, a local government must provide access to personnel, physical premises, data systems and data.

Geller said the statute provides the authority to review and issue a report and “doesn’t give them the authority to do anything else.”

DeSantis pointed out at one of his DOGE announcement stops — besides Fort Lauderdale, he and Ingolia made announcements in Gainesville and Bradenton — that non-complaint governments can be fined $1,000 a day for each violation, noting that if it involves 100 items it could be $100,000 a day.

As governor, DeSantis has other tools at his disposal to encourage compliance with his wishes.

The state can threaten to withhold money from local governments, something it did in July.

DeSantis’ transportation secretary posted on social media in support of a federal push to rid roadways of LGBTQ+ rainbow interchanges.

He attached a memorandum to the social media post that contained the hammer: threatening communities that didn’t comply with a loss of state funding. Unwilling to jeopardize millions of dollars in state transportation money, the three Palm Beach County cities — Boynton Beach, Delray Beach and West Palm Beach — with LGBTQ+ rainbow intersections removed them or said they would do so within weeks.

The governor has an even bigger club — the ability to remove county elected officials from their jobs. DeSantis has utilized that authority granted by the state Constitution much more than previous Republican governors. His predecessors largely limited themselves to removing people charged with crimes; DeSantis has used that power more expansively. He alluded to that authority during his DOGE announcement in Fort Lauderdale.

The two statewide organizations that represent local government officials in their dealings with state government and the Legislature, did not answer questions about Florida DOGE.

A representative of the Florida Association of Counties said they’d consult with an organization attorney about DOGE-related questions but ultimately didn’t provide any answers. A representative of the Florida League of Cities said the organization had “reviewed” questions but determined that “at this time we don’t have any additional information to share beyond what is already provided” by the governor’s office.

Florida DOGE is run out of the governor’s office, which also did not respond to questions.

Timeline

When President Donald Trump began his second term as president in January, he tapped Musk to lead an effort they called the Department of Government Efficiency to end federal programs and fire employees. Even though there was no formal department, the endeavor became widely known by its acronym DOGE.

In February, DeSantis got in on the action, announcing he was establishing a Florida DOGE task force to “uncover hidden waste” and “shine the light on waste and bloat” in state government and universities.

During the annual legislative session that finished in June, lawmakers gave DeSantis formal authority he sought to demand county, city, town and village governments comply with state demands for access and information.

Days after DeSantis appointed Ingoglia in July to fill the vacant state CFO position, they traveled to Fort Lauderdale together on July 22 to announce their first target: Broward County government.

Nine days later, a DOGE team managed by the governor’s office and drawn from the departments of financial services, revenue, transportation, commerce and education were at the Broward County Governmental Center in Fort Lauderdale.

Besides Gainesville getting a DOGE team starting Thursday, the governor’s office said Hillsborough, Pinellas and Orange counties and Jacksonville have been told to prepare for on-site visits.

Property taxes

DeSantis has frequently touted the idea of eliminating property taxes, and has promised that voters will see some kind of change to property taxes on the ballot in next year’s election. Ingoglia also has championed the idea. “We eventually want to get to property tax reform with the eventual goal of getting rid of homestead property taxes altogether,” Ingoglia said.

The governor hasn’t said how he’d replace the money that cities, towns, villages and counties receive from property taxes and spend largely on public safety, such as police and fire-rescue, and also for parks, libraries and a range of other services.

“I think what’s going on here is the governor wants to eliminate property taxes,” Geller said, adding that it would have the effect of defunding because the bulk of property tax money goes to police and other public safety spending.

Republicans Caruso, one of DeSantis’ staunchest allies in the Legislature, and LaMarca, who voted against all but one proposed county budget during the eight years he was a Broward County commissioner, said there is room to rein in spending and curb increases in property taxes.

LaMarca said he’d want to see specifics about any proposal that would go before voters to limit or eliminate property taxes rather than comment on a hypothetical.

Skidmore termed DOGE a political effort to find talking points that could help DeSantis sell an anti-property tax effort. “It’s a narrative. It’s not necessarily an accurate one or a truthful one,” she said.

She and Geller said that in a large government — Broward County’s annual budget is close to $9 billion, including Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport and Port Everglades — DOGE effort will find some things that look bad.

That does not mean there is anything inappropriate or corrupt, Skidmore said. “These are large, behemoth organizations and some things fall through the cracks. It happens in business, it happens in nonprofits, it happens in government.”

The parade float

Geller, Jewett and Skidmore said there’s lots of context needed to assess whether government spending is excessive or improper, much of which may get lost when sensational-sounding findings are brought to light.

DeSantis and Ingoglia have both cited Broward’s spending of $800,000 on a float in the 2024 Tournament of Roses Parade on New Year’s Day.

The money came from the tax visitors pay on their hotel stays, and can only be used for efforts aimed at promoting the county as a tourist destination, not on services that are paid with property tax money.

Geller said the professional staff at the Visit Lauderdale tourism promotion agency decided it was a good way to advertise the destination.

“DOGE may think that money would have been better spent on advertising on “NCIS” or “Real Housewives” or in full-age ads in the New York Post or the Wall Street Journal,” Geller said. “That’s a difference of opinion. … It’s not overspending, waste, fraud, abuse or mismanagement.”

©2025 South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Visit sun-sentinel.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments