No time, no lawyer, no rights: ICE memo sparks panic over third-country deportations

Published in News & Features

Immigrant communities across South Florida are on edge after a newly revealed immigration memo from the Trump administration confirmed that migrants could now be deported to countries other than their own with as little as six hours’ notice — even in cases where those countries offer no guarantees of safety.

The policy, laid out in a July 9 memo by Todd Lyons, acting director of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, expands the controversial use of “third-country deportations.” Immigration lawyers, human rights advocates and families say the rule marks one of the most extreme deportation tactics yet under President Donald Trump’s hard-line immigration approach.

“It is really chaos, what they are creating,” said Elizabeth Amaran, a Miami-based immigration attorney. “In practice, it’s almost impossible to notify someone in time. Six hours is not enough to prepare any legal defense — it effectively denies people due process.”

The Miami area, home to large diasporas from Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua and Haiti, has emerged as one of the regions most likely to be affected by the policy — and also one of the most politically sensitive. Many immigrants in South Florida are in legal limbo, with pending asylum cases or final orders of removal that haven’t been enforced.

Under the memo, first reported by the Washington Post, ICE is now authorized to deport non-citizens — including long-term U.S. residents — to third countries with only 24 hours’ notice. In “exigent circumstances,” that window can shrink to six hours, so long as the detainee is given an opportunity to speak with an attorney.

In cases where a receiving country has given “credible diplomatic assurances” that the deportee won’t face torture or persecution, ICE can carry out removals without any prior notice to the individual. Legal experts say this amounts to a sweeping removal power with few safeguards and little transparency.

“This falls far short of providing the statutory and due process protections that the law requires,” Trina Realmuto, executive director of the National Immigration Litigation Alliance, told Reuters. Her organization is leading a class action lawsuit against ICE in federal court over what it calls unconstitutional deportations.

The Trump administration has defended the policy as a necessary tool to accelerate the removal of unauthorized immigrants — including some with criminal records — particularly when their home countries are unwilling to accept them. “We need to get the worst of the worst out of our country,” Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem said Sunday on Fox News.

But data and accounts from immigration attorneys paint a different picture.

Amaran says the majority of detainees she knows of who are at risk under the policy do not have criminal records.

“Out of 14 people I know of who were detained recently, only three had any record at all,” she said. “Many have pending asylum claims or other forms of relief. They’re being deported before their cases can be heard.”

She added that many deportees are being sent to remote areas of Mexico despite not being Mexican nationals — and with no resources to survive.

“According to families I’ve spoken with, they’re bused to remote border areas, given a 15-day temporary permit, and then just left there. No money, no shelter, no plan,” Amaran said.

ICE’s new memo follows a Supreme Court decision in June that lifted an injunction on third-country deportations. In a dissenting opinion, Justice Sonia Sotomayor warned the policy would place “thousands of lives at risk of persecution and torture,” accusing the government of abandoning caution in life-and-death matters.

Since the ruling, the Trump administration has resumed controversial removals. Just last week, eight migrants from countries including Cuba, Sudan and Vietnam were deported to war-torn South Sudan — a nation engulfed in civil conflict. U.S. officials reportedly leaned on five African nations — Liberia, Senegal, Guinea-Bissau, Mauritania and Gabon — to accept deportees from other regions, such as Latin America and Southeast Asia.

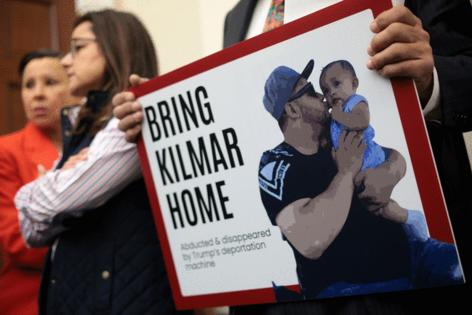

One of the most high-profile cases involves Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a Maryland resident wrongfully deported to El Salvador, despite a court order blocking his removal. After weeks of legal pressure, the Supreme Court returned him to the U.S., only for the Trump administration to threaten a new deportation — this time to an undisclosed third country.

While third-country deportations are not new, they were historically rare and limited. Under Trump’s first term, the U.S. deported a small number of Salvadorans and Hondurans to Guatemala. The Biden administration, while criticized for its own handling of immigration, struck regional agreements to manage migrant flows — including allowing Mexico to accept thousands of Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans and Venezuelans under specific terms.

What’s changed now, advocates say, is both the scale and the speed.

The memo requires ICE officers to provide “reasonable means and opportunity” for a detainee to speak with a lawyer, but Amaran says that’s far from reality.

“They say the person can talk to an attorney — but the system to actually make that happen doesn’t work. ICE routinely ignores scheduled calls. You can’t get a judge to rule on anything in six hours,” she said. “The deck is completely stacked.”

_____

©2025 Miami Herald. Visit miamiherald.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments