Cory Booker’s long speech offers a strategy for Trump opponents in a fragmented media landscape

Published in News & Features

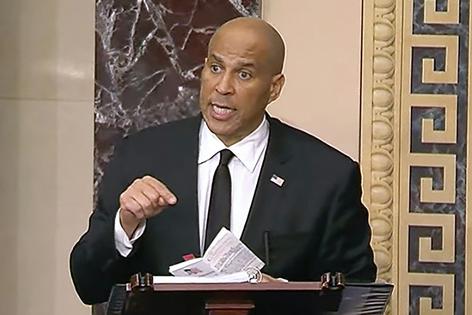

Sen. Cory Booker’s record-breaking, 25-hour Senate floor speech, which began on March 31, 2025, and ended on April 1, momentarily snatched the national spotlight from President Donald Trump.

The ever-churning national news cycle has already moved on from the spectacle.

But as communication studies scholars, we believe Booker’s speech offers important lessons for Trump opponents in a fragmented political and media landscape.

Our analysis of Booker’s speech, its media coverage and Booker’s use of online platforms to promote his marathon performance illustrate one way to disrupt the constant public spotlight on Trump.

In research published in 2023, we compared filibusters and long speeches in the United States and overseas. The long speeches we examined took place in national parliaments and political party meetings across the world.

Our research uncovered three patterns.

Long speeches incorporate varied topics and texts. Whether or not these digressions are relevant to the issue at hand, they make the speaker’s remarks last longer.

In Sen. Rand Paul’s nearly 13-hour filibuster of John Brennan’s CIA nomination in 2013, for example, he read articles on drone warfare alongside a portion of “Alice in Wonderland.” And Sen. Alfonse D'Amato’s 1986 filibuster of a military spending bill included a partial reading of the District of Columbia phone book.“

Long speeches also include expected interruptions to the speaker’s performance and address a variety of audiences.

That’s what happened during Sen. Strom Thurmond’s 1957 filibuster of the Civil Rights Act – the longest speech on the Senate floor before Booker’s performance. When Thurmond needed a bathroom break during his 24-hour, 18-minute filibuster, Sen. Barry Goldwater assisted by stalling with a report on military preparedness.

These patterns of topical digression and expected interruption challenge the image of filibusters as individual acts of continuous endurance promoted in films such as ”Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.“ And they apply to Booker’s Senate speech.

Our research also demonstrated how the media reframes the complexity of long speeches into simplified narratives. This coverage sometimes differs as different outlets target varied audiences.

News reports on Thurmond’s filibuster bolstered an image of him as the lone senator defending segregation while the rest of the Senate slept.

After state Sen. Wendy Davis’ filibuster of a 2013 anti-abortion bill in Texas, supporters linked the filibuster to her rising political prospects, while opponents disparaged her with the nickname Abortion Barbie.

These reactions do not grapple directly with the wide-ranging content of long speeches. But they do allow them to reach audiences in ways that can shape popular memory of the event.

Like other long speeches we have studied, Booker’s Senate speech addressed several topics.

Booker read a passage from the Federalist Papers that advocated for constitutional checks and balances on the executive branch. At another point, he quoted federal appellate Judge Learned Hand, who was called the "Tenth Justice” of the Supreme Court in the first half of the 20th century. Booker also used personal anecdotes that linked his parents to the civil rights struggle and reflected on his first senate campaign.

But mainstream news stories covering Booker’s speech produced a largely coherent summary of the overall point of the marathon talk – as they saw it, it was a stand against Trump.

Booker’s speech also aligned with another convention of long speeches – his monologue was broken up by the parliamentary questions of fellow senators.

Numerous Democratic allies gave Booker a break as they introduced issues of their own interest. Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar, for example, used her time to discuss Bob Dylan.

After the speech, however, many news outlets focused on Booker’s physical feat. This directed attention away from the hodgepodge of voices and sources in the speech.

Fielding reporters’ questions after yielding the Senate floor, Booker discussed his use of fasting to prepare. And The New York Times reported on the effects of standing for so long and not sleeping.

Debates about whether or how speakers stop to use the bathroom are a source of enduring fascination surrounding long speeches. It’s something that Thurmond biographer Joseph Crespino calls the “urological mystery.”

Media fixation on Booker’s body reimagined him as the sole speaker.

When Booker broke the record, roughly 115,000 people were streaming the speech on YouTube. A TikTok livestream of the event received 350 million likes by the end of the day.

Booker was prepared for this online attention. Throughout the speech, he repeated a strategic set of phrases. Those ranged from “Let’s get in good trouble” – a reference to the late John Lewis, a Georgia Democrat who served in the U.S. House of Representatives, that appeals to Booker’s political base – to “This is a moral moment,” a slogan that evokes Rev. William Barber II’s broad-based “moral movement.”

After the speech, Booker repeated these taglines on social media, at a New Jersey town hall and in interviews with national media.

Trump’s “flood the zone” approach to policymaking, which occupies media coverage through overwhelming activity, has been widely discussed by the media.

Booker’s speech demonstrates that for resistance to be effective, it must be noticed.

His use of easily excerpted catchphrases targeted media platforms built around short, viral video clips. The length of Booker’s speech made it newsworthy, but short clips are necessary to sustain attention online.

On April 2, news commentators and media outlets posed a number of questions that were not about Trump: Why did Booker speak that long? How did he prepare? Was he wearing a diaper?

These questions are part of the simplifications that occur in response to long speeches, and the media briefly paused from constant Trump coverage to ask them again.

Other coverage has noted that Google searches for Booker have increased since the speech – and it has speculated whether the speech might improve Democratic Party approval ratings.

More recently, an April 13 op-ed in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution picked up on Booker’s use of “good trouble” and declared, “Cory Booker is following in footsteps of Rep. John Lewis.”

By grabbing hold of a stage and not letting go, Booker became a figure of focus for at least one news cycle.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Erik Johnson, Stetson University and Matthew deTar, Ohio University

Read more:

Politics with Michelle Grattan: Warwick McKibbin on trying to model economic certainty in uncertain times

Donald Trump’s nonstop news-making can be exhausting, making it harder for people to scrutinize his presidential actions

Most US states don’t have a filibuster – nor do many democratic countries

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments