Across San Diego, students, parents and educators raise alarm over funding cuts to schools, research

Published in News & Features

Dozens of arms shot toward the midday sun Tuesday at UC San Diego when a protest organizer asked roughly 200 students if they work in laboratories whose research funding has been cut by the Trump administration.

Seconds later, the crowd was chanting “Stand up, fight back!” — the kind of phrase that demonstrators across the country were using during a coordinated day of action dubbed “Kill the Cuts.”

Hours earlier, a few dozen educators, parents and others had rallied against school funding cuts in downtown San Diego, just outside a hotel where the nation’s top education official was speaking at a conference.

The La Jolla protest was organized by the labor union that represents 48,000 academic workers in the University of California system, including about 8,000 at UCSD, the nation’s sixth-largest research school.

UCSD disclosed last week it could face potentially $500 million a year in budget cuts — a figure more than twice as high as one that the school issued in February. Those cuts could fall heavily on student researchers and other workers.

Some individual research cuts have already begun to hit.

“At this time, roughly 40 grant awards have been impacted by disruption notices, including stop work orders, terminations, and funding freezes,” UCSD told The San Diego Union-Tribune on Tuesday in an email. “The total value of these grants over their lifetime is $59 million, and they are at various stages of completion.”

The losses are causing deep anxiety at UCSD, as students’ remarks Tuesday to the Union-Tribune underscored.

“In the past couple of months, I have absolutely considered moving out of academia and looking for other options, even in other countries,” said Sutanay Bhattacharya, who is pursuing a PhD in mathematics. “This has been a devastating time for me.”

Udayan Tandon, a doctoral student in computer science, was equally upset.

“We’ve started to hear a little bit about layoffs, postdocs being laid off,” he said. “Incoming students aren’t getting the funding guarantees that we got when I came in. That is deeply concerning.”

Due to financial problems, UCSD said last month it can’t guarantee that the first-year graduate students who enroll this fall will get their full stipends and tuition. Such guarantees were common in the past, and for many students provided much of the money they needed to earn a doctorate.

The decision “represents a real lack of job security for those students,” said Sarah Van Dijk, a doctoral student in the biomedical sciences.

To Gwen Frank, a doctoral student in engineering, much more than her job is at stake.

“I’m worried about our ability continue to do good science,” she said. “The reality is academia is set up in a unique position to do the type of high-risk research that corporations can’t. A lot of time that research is saving lives.”

This represents an existential moment for Danea Palmer, a doctoral student in biochemistry.

“I have already had to think of, What is Plan B if our lab runs out of funding?” she said. “I want to pursue my dream of helping human health. I don’t know if that’s going to be possible.”

Hours before the UCSD gathering, K-12 educators and supporters assembled in front of the Manchester Grand Hyatt hotel downtown to protest President Trump’s efforts to dismantle the Department of Education and their impacts.

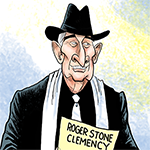

Inside, the agency’s top official, Education Secretary Linda McMahon, was speaking at the ASU+GSV Summit, cohosted by Arizona State University and Global Silicon Valley.

Speakers warned the cuts would especially hurt special education and students who are disadvantaged.

Laurie Kern, who has two neurodivergent daughters in Cajon Valley Union School District, said that often public schools are the only schools with the infrastructure and community to support some students with disabilities. She worries the administration’s ultimate goal is to privatize education.

San Diego Unified School Board President Cody Petterson said his district has seen its Title I funding, which supports high-poverty schools, delayed by more than a month.

Last week, the Trump administration threatened to withhold such funds unless state education officials vow they’ve done away with diversity, equity and inclusion practices.

Petterson said that because California residents and businesses pay far more in federal taxes than they get in federal spending, Title I funding is California taxpayers’ money returning home.

“We depend on Title I funding for our most vulnerable students, our low-income students, our students in foster care and our English language learners,” he said. “It’s really what we use to backfill the austerity that all of education sees in America, and particularly in California.”

Petterson also pointed out that the district is currently under an agreement with the federal agency’s Office of Civil Rights governing how the district handles sexual misconduct allegations under Title IX. The district has reorganized its Title IX office and practices, after a federal investigation found it systematically failed to protect its students.

The Office of Civil Rights was cut in half last month.

“It’s never great to be investigated by the Office of Civil Rights,” Petterson said Tuesday. “But I’m going to tell you — that is part of accountability … We depend on the Office of Civil Rights to keep us accountable.”

_____

©2025 The San Diego Union-Tribune. Visit sandiegouniontribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments