Trump keeps talking about taking Pacific Northwest water -- is that possible?

Published in News & Features

The answer is no.

President Donald Trump has not and cannot take water from the Pacific Northwest and send it somewhere else, such as California.

There are quite a few reasons why that's just not possible, but before we get into those, let's take a look at Trump's recent statements.

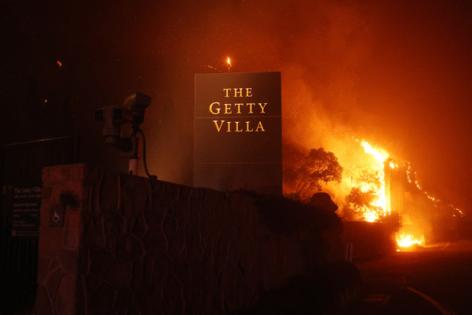

Following the devastating wildfires throughout the Los Angeles area, Trump blamed them on a lack of water because California officials had sought to protect a threatened species of fish. The president was wrong in his assessment at times, experts repeatedly noted, or he was oversimplifying complicated hydrological issues.

The president plowed forward anyway, ordering the release of water from reservoirs in Central California. And while he claimed "Victory!" on social media, that water won't reach parched Southern California because the two regions aren't connected in that way. At the same time, state officials there worried the releases wasted water ahead of the summer, when farmers will need it most.

"The United States military just entered the great state of California and, under emergency powers, TURNED ON THE WATER flowing abundantly from the Pacific Northwest, and beyond," Trump wrote on social media.

That's not true.

Trump has talked of taking water from the Pacific Northwest multiple times. He didn't invent the idea; it's been around for generations and has never really gained momentum. The notion won't work for a variety of reasons, water managers and legal experts say, and should instead be relegated to the heap of failed environmental proposals.

"It's just factually, economically, legally and politically mind-bogglingly stupid," said Daniel Rohlf, an environmental law professor with the College of Lewis and Clark in Portland.

Here's why the idea won't work.

The regions aren't connected

This is the simplest and most obvious reason. There is no physical way to transport water from the Pacific Northwest to Southern California. No pipelines, no canals or aqueducts.

You probably would have heard about it if there were a way to move water from the Pacific Northwest south. Canals like the 336-mile Central Arizona Project, diverting Colorado River water into the deserts of central and southern Arizona, are massively expensive and controversial. They take billions of dollars and years, if not decades, to build.

The more technical way to phrase it is there is "no existing conveyance" from the Pacific Northwest into Southern California, said Ria Berns, who manages the Washington State Department of Ecology's Water Resources Program. Nor has anyone realistically proposed or discussed building that type of infrastructure recently, she said.

We do transport water all the time, especially within the Columbia River Basin. We can funnel it out of a river for irrigation, hydropower and our cities.

Since Oregon and Washington both border the Columbia River itself, the two states do have ways of moving water back and forth between each other. But these are relatively short-distance transfers, nothing on the order of the 1,000-mile journey into Southern California. And even then, these transfers generally flow from Oregon into Washington, not the other way around, Berns said.

Transporting water between the two disparate regions just isn't physically possible, Rohlf said.

There's no water to spare

Washington has lagged behind in winter snowpack, which provides water during the summer months. Even if outside agencies wanted to take water out of Washington, the state doesn't have any to spare.

We're in the middle of a snow drought, meaning we're short on the snowpack that accumulates over the winter, melts during spring and early summer and provides water through the hottest and driest time of year. As the global climate warms, hydrologists anticipate Washington will experience a snow drought through about 40% of the winters ahead.

Last year and the year before, state officials declared a drought emergency. Technically we're still in the emergency declared last April, and soon these officials will consider whether our lagging snowpack justifies a third drought emergency.

All to say, Washington's not exactly flush with water right now, so sending the resource out of state (even if that were physically possible) isn't in the cards.

That means, Berns said, that Washington's water managers are looking at how best to maximize the water we have for our people and the environment. Don't forget, fish like salmon need water too. They also have a legal right to the resource.

Oregon is in better shape with its snowpack right now, though state officials there also declared a drought emergency last year.

Legal problems

Even when there is enough snowpack and enough water flowing through Washington's rivers and streams, it's all spoken for, Berns said.

"Washington water is for Washingtonians," Berns said.

Like other states across the American West, Washington has a long and complicated system of water rights, many of which date back more than a century. All the water that's available to be used along the Columbia River, for example, is connected to someone's existing water right.

To take water out of these rivers and streams would mean to shortchange families, farms and other companies that rely on it. Already some of those people have faced water cuts because of the drought.

Violating these rights, especially to cross state lines, would create a slew of additional legal problems, Rohlf said.

Nobody else is on board

An important point to note, Rohlf said, is none of the states involved have backed Trump's idea.

"No one in California — I mean no one — is saying, 'Gee, let's have a pipeline up to the Pacific Northwest,'" he said.

Washington isn't on board either, Berns confirmed. And while officials in Oregon declined to comment for this article, no policymakers there have seriously proposed any such transfer either.

The most cost-effective and efficient way to address water shortages in a given region is to find local solutions like conservation and — some might argue — adding new storage reservoirs, Rohlf said.

Public officials of all stripes have long considered taking water from the Pacific Northwest and sending the resource somewhere else. In 1947, Congress considered taking Klamath River water and sending it south. In the 1950s, the North American Water and Power Alliance considered taking water from even farther north, up in Canada, to spread all across the continent. In the 1990s, Los Angeles County Supervisor Kenneth Hahn suggested piping Columbia River water down to Southern California. The list goes on.

Estimates for each idea have run into the billions of dollars, and one by one the proposals were shot down as too expensive, environmentally damaging, politically risky or downright impossible.

Trump's comments are just the newest addition to that long list of ideas that haven't gone anywhere, Rohlf said.

_____

© 2025 The Seattle Times. Visit www.seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments