Would you pay $12 for a cup of coffee in San Diego?

Published in Business News

Your cortado, cold brew and tulip topped latte all cost a lot more than they did a few years ago.

As $2.25 espresso double shots increased to $4, San Diego coffee and espresso drinkers proved they are willing to pay more.

But how much more?

Talitha Coffee Roasters decided to ask its customers. The San Diego company, which sells wholesale roasted beans and has nine cafes under the Talitha and Lofty Coffee brands, last month surveyed more than 200 people with this question: “What is the absolute highest amount you would pay for your favorite cup of coffee?”

Around 56% said they’d be willing to spend $6 to $8 for their favorite drink. Almost 37% said they would spend $3 to $5. Around 4.5% said $9 to $11 is tolerable. All together, 97% were not willing to pay more than $8. At the low and high end, 1.5% were willing to spend at most $3, and around 2% said they were OK to pay $12 or more.

The survey results showed that Talitha’s menu, which is similar in price to many other San Diego cafes that sell high-end coffee and espresso, hits an economic sweet spot, with most people accepting today’s higher prices, but few willing to pay much more.

The broad range of price tolerance, from less than $3 to more than $12, offers a window into how consumers view record-high prices — and how they see coffee itself. Is it a treat or a necessity? Is it a caffeine delivery system or an opportunity to partake in a magical moment: laptop, book or friend at your table, Nina Simone in the background, hum of people typing or chatting all around, and wrapping your hands around a toasty mug?

The survey results are not surprising given the small sample size and who it asked: Talitha’s own customers, who seek out organic coffee and live in a high cost of living region.

Greg Peters, the vice president of operations of Talitha Coffee Roasters, said the poll confirmed his expectations.

“I think our cafe customers, more than anything, value the experience,” he said. “Our house espresso is organic. They’re sustainably … ethically sourced coffees. We use high quality ingredients and provide a really nice space for people to have a sense of community.”

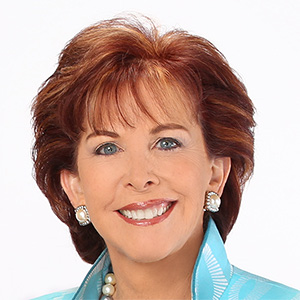

Nor were they surprising to Kate Johnson, a financial adviser with Northwestern Mutual in San Diego, whose team works with more than 300 households across the U.S.

“I think what’s unique about coffee is it is a nonnegotiable for a lot of people,” Johnson said.

As prices have swelled across the board, for beef, eggs and rent, expensive coffee blends in with everything else.

“It is easier to justify spending two extra dollars,” Johnson said. “We’ve been feeling the cost of living, the cost of goods, go up since COVID. … And so, by this point in time — it’s been five years — I don’t think people are quite as sensitive as they had been.”

Johnson also noted that the survey took place around the holidays, when spending goes up, and there’s a mentality that “it’s time to treat ourselves.”

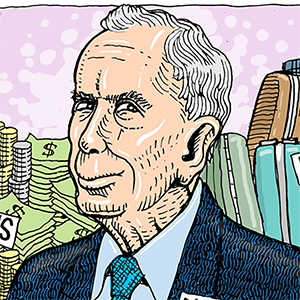

Alan Gin, a professor of economics at the University of San Diego, said people’s differing abilities to buy expensive coffee can be explained by what is called a “K-shaped” economy, which illustrates the growing gap between affluent consumers and those who are struggling financially. One arm of the K points up, and one points down.

At the lower end, many consumers are under “a lot of stress right now,” Gin said. Ethically sourced, well-crafted coffee is not a critical need, so “that’s one of the things consumers are likely to try to cut back on in order to afford the necessities.”

But, he added, “not everybody is going to cut back. Prices are rising, people are under stress, but some people are in a little better shape. So people are going to these places, willing to spend that amount. They might be able to weather that, and put up with that, because they’ve fallen in love with the product.”

Overall, Gin said, he expects higher retail prices “will have some impact” on cafe sales, as some customers are priced out.

How cafes deal with rising coffee prices

For San Diego coffee business owners, deciding how much to charge and when to raise prices is, on one hand, simple math based on their costs.

On the other hand, it is a delicate balancing act between customer budgets and business bottom lines. Raise prices too much, and sales take a hit. Don’t raise prices enough and you won’t meet your rising costs.

“Price increases are not something that we want to do every couple of months, or every three months or even twice a year,” said Peters, with Talitha. “That just creates distrust with our customers.” Talitha typically adjusts prices once a year, though it recently did a small increase a few weeks ago, he said. He declined to say how much prices have gone up, sharing only that “our prices were increased based directly on our cost of goods” and improved efficiency has allowed the company to absorb some added costs.

At Bird Rock Coffee Roasters, which has 11 cafes and also roasts for wholesale accounts, the approach to raising prices is slow and thoughtful. Year over year, some retail prices are up around 6 to 7%, depending on the product.

“Our prices only went up out of necessity,” said Jeff Taylor, the president of Bird Rock Coffee Roasters. Customers have been understanding, he said. The cafes had seen a decline of up to 2% in the number of sales tickets on a given day, but that has rebounded.

“Our retail sales are up just slightly over last year. Traffic had slowed slightly in November, but the holidays have been good, and traffic is back up,” he said.

Not raising prices is not an option, the two San Diego coffee chains said, because their costs have gone up sharply.

Coffee’s price on the global Arabica coffee commodity market reached a record high of more than $4.25 a pound in early 2025. It has since fallen off that peak to around $3.50, but is still more than double what it was before the pandemic and in recent years, as prices have fluctuated.

“Relatively speaking, that’s still extremely high,” Peters said.

On top of that commodity price, different coffees extract a “differential,” or premium, depending on supply and demand. Other opportunities for markups include transportation and warehousing.

Peters described the causes of rising prices as “a perfect storm” — an apt pun, because a primary factor is climate change. Consistent drought in Brazil, the world’s largest coffee producer, has led to smaller harvests, even as farmers look to irrigation over rainfall to recover production.

“Not only are prices going up in Brazil because of lack of supply, but that has a ripple-down effect and affects everybody else,” Peters said.

Coffee is increasingly in demand in China, where coffee drinkers prize beans from parts of Central and Latin America, which raises the prices for those products on the global coffee market.

Tariffs introduced by President Trump caused prices to rise further. “That peak of the coffee market did not include tariffs,” Taylor said. “These tariffs were on top of that high price. Those were 40 or 50 cents as well, to the pound of coffee.”

Peters, with Talitha, added that the uncertainty has been the hardest aspect of the tariff trade policy.

“With the tariffs being implemented and then taken away, and implemented and then taken away, we’ve just had to delay contracts. It just creates a ton of uncertainty,” he said.

Coffee is bought and sold in contracts that get fulfilled months or up to one year out. While in some cases tariffs against certain countries have been reduced or removed, purchases made at the earlier, higher prices are still in inventory that needs to be sold.

Both cafe operators said connected expenses are also up: the energy to roast, the cost of packaging, paper cups, milk, labor and equipment.

Today’s higher prices for a cup of joe pass the economics professor’s sniff test.

“I think it is legitimate,” Gin said. “The cost of producing a cup of coffee has risen dramatically, starting with the base of the coffee itself, and then other things like labor cost, the cost of supplies and things like that — complements to the coffee. So I would buy their argument that they had to raise the prices.”

A further test will come down the line: if commodity coffee prices drop, will retailers adjust their menu prices?

“The thing to look for is whether prices will come down rapidly in the future, once the cost of coffee starts declining,” Gin said.

Necessary treat?

Some people can spend $8 on 12 ounces of steamed milk and espresso without flinching. For everyone else, shelling out for higher and higher priced coffee comes down to trade-offs.

One is between coffee and other treats, said Johnson. Normally, when prices go up, demand drops. But coffee is an attainable splurge. So it might veer from that norm.

“It sits in an interesting price point, right?” Spending $8 on a fancy coffee is “a lot easier of a splurge to justify than a fancy dinner.”

And when bigger luxuries are the first to go — vacation, new car, dinner out — holding on to a smaller splurge is a way to keep indulging.

Another trade-off could be between coffee and caffeine. For people who see caffeine as fuel, shifting to something cheaper like an energy drink is fine. But for those who can taste the difference between an appropriately roasted and pulled single origin shot and a stale blend, gas station coffee is a tough sell.

“Once you start drinking high-quality beer — it’s the same thing with coffee. It’s really hard to go back,” said Peters, who worked in the craft beer industry before turning to coffee. “I mean, years ago, I used to drink crappy coffee, and then I started drinking better coffee, and then I started working in the coffee industry. And now, it’s tough. Like, if I get a bad cup of coffee.” His voice trailed off, as if the thought were too painful to finish aloud.

Johnson has found that for some of her clients, quality coffee is essential.

“Obviously, I can’t speak for every single person, but I think if you’re a connoisseur of coffee, it’s probably not something you want to compromise on. But you may be willing to compromise somewhere else to fill in the gap,” she said.

She put herself in that category, saying, “I love a phenomenal cappuccino, and I’m willing to pay a little extra to get one.”

_____

©2025 The San Diego Union-Tribune. Visit sandiegouniontribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments