Trump's pick for Fed's top regulator expected to be friendly to Wall Street

Published in Business News

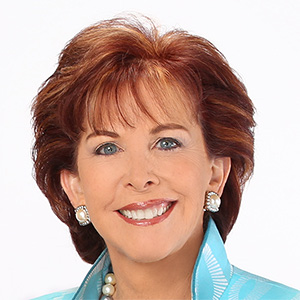

A red baseball cap sits above Michelle Bowman’s filing cabinet in her office at the U.S. Federal Reserve in Washington. It’s emblazoned with the words “make community banks great again.” The TV in her office is tuned to Fox News, and the self-described workaholic has a sticky note on her door asking visitors to knock loudly because the door is heavy.

Already a Fed governor, Bowman is likely to become one of the central bank’s key leaders, in charge of banking regulation. The Senate Banking Committee voted along party lines to advance her nomination as vice chair for supervision, and the full Republican-controlled chamber is set to vote on her confirmation on Wednesday. The industry has praised Bowman’s nomination, highlighting her drive to scale back a massive bank-capital proposal that it says will hurt lending, erode its competitive edge and potentially reduce economic growth. Critics are concerned that she’s too focused on what banks want — at a time when the White House is embarking on a deregulatory drive, threatening the Fed’s independence and introducing tariff-fueled economic uncertainty that could put the financial system under pressure.

That she’s in line for the job now is due to Michael Barr’s surprise announcement that he would leave it. Barr stepped down in February while remaining a governor, even though his term as vice chair extended to July 2026. He wanted to avoid a protracted legal fight over a possible demotion by Trump.

Bowman, who asks everyone she meets to please call her “Miki,” quickly made her interest in the job clear. She talked to state bank regulators who had lobbied to get her onto the Fed board in 2018, according to people familiar with the matter who didn’t want to be identified discussing the private communications. She asked some of them to signal to Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent that he should push Trump to fill Barr’s seat rather than leave it vacant, and pitched herself as a regulatory insider who wouldn’t even need to wait for Senate confirmation to get started. Industry players like the Independent Community Bankers of America and the American Bankers Association also rallied behind her. Bowman herself points to the experience she has gained in an eventful last seven years.

“I’ve seen a lot since I’ve been here at the Fed,” says Bowman, 54. “We’ve seen the entire shutting down of the economy and restarting it again.”

She will have to navigate a position that has been an awkward fit for the Fed, an agency that strives to remain as apolitical as possible in setting monetary policy. The supervision job was created by the Dodd-Frank Act in response to the 2008 financial crisis. Chair Jerome Powell himself has said that placing the burden of developing recommendations on a single person rather than the entire Fed board has made bank policy more volatile.

Bowman has deep roots in small-town banking. Born in Hawaii, she spent time living in Germany as a part of a military-kid upbringing, and worked in the UK. But home has always been rural Council Grove, Kansas, about 90 miles northeast of Wichita. “The closest town is about 35 miles away with a 2,200 population,” Bowman says. In Council Grove, she worked at Farmers & Drovers Bank, which her great-great grandfather helped charter in 1882, before becoming the Kansas state banking commissioner in 2017. A lawyer, she also previously worked in Washington as counsel to U.S. House committees and as a policy adviser in the Department of Homeland Security during the George W. Bush administration.

She was first nominated to the Fed board by Trump in 2018, to fill a position designated for an expert on community banks, which have long been losing market share to bigger lenders. Since then, Bowman has criss-crossed the country — by her count visiting all but four states. She has given detailed speeches to community banking groups on how vital these lenders are to the economy. Her travels across the U.S. and to five continents rival only Powell, among her board colleagues, in the number of engagements. Over time, she has become more vocal, often supporting easing regulations that she says are too burdensome for the smallest banks.

Her missives on regulation were often a foil to Barr’s attempts to significantly increase capital requirements for banks — that is, to have them further pad their financial cushions, depending on the risks they take, so they can absorb losses during a crisis. “My greatest concern about Governor Bowman is that I haven’t seen any daylight between her publicly stated positions and the wish list of the largest banks for lower capital requirements and less demanding supervision,” says Arthur Wilmarth, a professor emeritus at George Washington University Law School who was a consultant to the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission created by Congress. That could change if she prioritizes coalition-building with other members of the board, he says.Bowman says regulation already has put banks on firmer ground. “We’ve created a much stronger, safer, sound banking system,” she says.

‘Thorny issues of Fed independence’

The vice chair job is probably the most demanding in all of financial regulation, says Graham Steele, a Fed alumnus who also served as a Biden-era Treasury official. He adds that it’s a step up in difficulty from being a single governor with one vote and giving speeches on personal views. “That person has always had to balance a complex and delicate set of policy, political and procedural issues while finding consensus between and across the views of the other banking agencies and the Fed’s board members,” Steele says. “In this administration, they now also have to navigate thorny issues of Fed independence with a White House that’s seeking to bring independent agencies under political control, including the Fed’s regulatory functions.”

As a board member, Bowman will also continue to have a voice in monetary policy. In that realm, she has been somewhat more hawkish on interest rates than her colleagues. She cast the first dissenting vote by a governor in almost 20 years when she voted against the Fed’s decision to cut interest rates by half a percentage point in September. That was the first cut since the start of the pandemic; Bowman argued that a smaller, quarter-point cut would have been more appropriate given that inflation was still above the central bank’s 2% target.

She has a reputation for toughness. People who asked not to be identified discussing internal Fed matters said that tense interactions between Bowman and Fed staff led to a new practice where more senior officials with titles brief her and other governors on policy matters. But some observers see her style as a benefit. She dives into the details and makes sure she understands an analysis and its policy implications, says Mona Elliot, a former Fed official who now advises clients at Patomak Global Partners. “Ultimately, what the governors care about is really understanding the potential impact of the decisions that they’re making,” said Elliot, who briefed Bowman at the beginning of her time at the Fed in 2018.Randal Quarles, who held the supervision role before Barr after being chosen by Trump in 2017, says the highly qualified staff at the Fed has a culture that can sometimes be “too sure of itself” and that this is ripe for change.

Bowman has been willing to take on high-profile fights. Shortly after Silicon Valley Bank collapsed in 2023, she started calling for an independent review into what failings led to the lender’s fast fall. Barr did his own review, which he called an “unflinching look” at problems in both the supervision of the bank and the regulatory requirements for an institution of that size. Some critics said the details were vague, and Bowman has insisted the report is insufficient in terms of full accountability and transparency. She has said she wants to launch a third-party review.

COVID-19 lockdowns

During the 2020 COVID-19-induced lockdowns, Bowman was anxious about the Fed not being able to read the economy as the government was offering loans to businesses via banks using the Paycheck Protection Program without a lot of guidance or directives. She began a campaign to reach as many of those lenders as possible. Over the next year, she managed to talk to more than 220 community-bank chief executive officers in 30-minute phone calls. “I think that really helped allow them to engage with confidence and continue to be the greatest lenders in that program,” she says.

Before that campaign, she worked to get her arms around the Fed’s consumer compliance program. After hearing complaints about banks waiting three to five years for an exam report, she championed an effort to make the exam process more timely, while preserving its effectiveness.

To help advise her, Bowman has turned to the banking world for three staff hires, who recently joined the agency’s Division of Supervision and Regulation. Two sweeping proposals are on her radar: a landmark Biden-era bank-capital plan known as Basel III endgame and long-term debt requirements that would affect all lenders with more than $100 billion in assets. As originally drafted, the Basel plan would have hiked the biggest U.S. banks’ capital requirements by 19%. The Fed walked it back after fierce industry opposition. Bowman is widely expected to support dramatically easing the requirements. She also plans to rescind the proposal to bolster long-term debt requirements, according to people familiar with the matter.

Bowman sided with the industry on its calls to increase the transparency of the Fed’s stress tests, which gauge how large banks would fare during a hypothetical recession. And she’s working with other Trump regulators on potential changes to a rule—the so-called supplementary leverage ratio—that has constrained banks’ trading in the $29 trillion Treasuries market.

Bowman has said she wants to keep the Fed’s experienced ranks of bank supervisors and examiners, arguing that they’re critical to the Fed being able to carry out its regulatory responsibilities. Already, the Trump administration is set to shrink the staff of other financial regulators by more than 2,300, including examiners. The Fed plans to reduce its workforce by about 10% in the next couple of years, but it isn’t clear whether that would include examiners.

“Our examinations staff are of the most importance when we’re talking about how we execute our responsibilities under supervision for the safety and stability and soundness of the banking system,” Bowman said during her Banking Committee nomination hearing in May. “If I were to do a review of our supervision and regulation division, should I be confirmed, I would certainly be very sensitive to the fact that we need to be able to fully and effectively implement our responsibilities for bank regulation.”

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments