Business

/ArcaMax

Tech review: Two dash cam systems keep an eye on your trips

I love watching the evolution of gadgets.

I’ve been around long enough to remember a time before we had a lot of the gadgets we take for granted today, like smartphones or laptops and today’s topic, dash cams.

Today we are looking at two dash cams, the 4K A810S from 70mai and A329S from VIOFO.

Both offer 4K recording and tons of other ...Read more

County prosecutors probing whether Edison should be criminally prosecuted for Eaton fire

The Los Angeles County District Attorney is investigating whether Southern California Edison should be criminally prosecuted for its actions in last year's devastating Eaton wildfire, which killed 19 people and left thousands of families homeless, the company said Wednesday.

Pedro Pizarro, chief executive of Edison International, told Wall ...Read more

Boeing defense headquarters moving back to St. Louis

ST. LOUIS — The Boeing Co.'s defense, space and security division headquarters is moving back to St. Louis, the company said in a news release Wednesday.

The division operated out of St. Louis from 1997 to 2017 when Boeing moved the defense headquarters to Arlington, Virginia.

The relocation is effective as of Wednesday, and there is not a ...Read more

DMV decides not to suspend Tesla sales in California over deceptive marketing

Tesla sales won't be suspended in California after regulators ruled Tuesday that the electric vehicle company has stopped misleading customers about its driver assistance features.

In December, the California Department of Motor Vehicles found Tesla in violation of state law for exaggerating the capabilities of its "Autopilot" and "Full Self-...Read more

Google Gemini, Apple add music-focused generative AI features

Alphabet Inc.’s Google and Apple Inc. are adding music-focused generative artificial intelligence features to their core consumer apps, underscoring how advanced AI tools are moving into mainstream use.

Google’s Gemini AI assistant can now create 30-second music tracks based on text, photos or video uploaded by users using Google DeepMind�...Read more

Unprecedented 'jobless boom' tests limits of US economic expansion

The U.S. economy is creating plenty of wealth. It’s just not creating many jobs.

Forecasters expect Friday’s report on gross domestic product to show the economy expanded 2.7% in 2025, a solid pace by any standard for a developed country. But employment barely grew, and the combination is drawing comparisons to the infamous “jobless ...Read more

Feds kill rule that promoted EV production to meet mpg standards

WASHINGTON — The Trump administration said Wednesday it is eliminating a regulatory wrinkle that boosted the miles-per-gallon ratings of electric vehicles, which helped automakers meet federal fuel economy targets.

The announcement follows an appeals court decision in September and a complicated Biden-era standoff between automakers and ...Read more

OpenAI blocked from using Cameo name for its AI video features

OpenAI has been temporarily blocked from using the word "Cameo" in a product that allows people to generate videos based on prompts amid a trademark dispute.

Last year, the celebrity video platform Cameo sued OpenAI, alleging that the San Francisco company infringed its trademark. People use Cameo to purchase personalized videos of celebrities ...Read more

How Ford's 'skunkworks' team is designing a more efficient EV

Ford Motor Co. engineers assigned to work on the Dearborn, Michigan, automaker's new electric vehicle platform often take several months to transition to the group's different approach to vehicle development, the team's executive director said.

Ford a few years ago broke off a small team of engineers and designers it called "skunkworks" in ...Read more

Mayo Clinic testing Israeli magnetic-heating technology as cancer treatment

Anyone who has used an induction cooktop to boil noodles is halfway to understanding Mayo Clinic’s new experimental approach to killing cancer cells.

The Rochester-based health system announced Tuesday it is the first in the U.S. to test Israeli technology that targets solid tumors with fast-rising heat, or hyperthermia.

“Temperature is ...Read more

General Mills lowers sales, profit outlook as stressed consumers spend less

General Mills is forecasting a drop in sales this fiscal year as many Americans continue to cut back in the grocery aisle.

The Minnesota-based food company lowered its outlook in the face of “historically low consumer sentiment, heightened uncertainty and significant volatility,” CEO Jeff Harmening said at the Feb. 17 Consumer Analyst Group...Read more

Weeks before studio negotiations, the Writers Guild of America's staff union goes on strike

The Writers Guild of America West's own staff union is officially on strike.

According to a release, the staff union called for an unfair labor practice strike on Tuesday afternoon, alleging management has shown no intention to come to an agreement on the pending contract. Among its accusations, the labor group also said that guild management ...Read more

Warner Bros. Discovery reopens bidding, gives Paramount 7 days to make its case

LOS ANGELES — Warner Bros. Discovery is cracking open the door to allow spurned bidder, Paramount Skydance, to make its case that it should win the legendary entertainment company — the latest twist in the contentious, high-stakes auction.

Warner's decision to reopen talks comes after weeks of pressure from Paramount and its controlling ...Read more

US, Nippon Steel to reline Gary Works blast furnace this year

U.S. Steel’s Gary Works facility, later this year, will receive its blast furnace reline through Nippon Steel’s investment into the American company.

Some Gary residents and activists are still opposed to the reline, saying they don’t believe it’s the best move environmentally.

The reline for blast furnace #14 will cost $350 million ...Read more

$7.25 billion settlement pitched in Bayer Roundup case. St. Louis court to review

ST. LOUIS — Agri-chemical giant Bayer has agreed to a proposed $7.25 billion class-action settlement, a big step toward resolving thousands of lawsuits claiming that exposure to the weedkiller Roundup caused non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Tuesday's proposed settlement would pay people across the United States exposed to Roundup and diagnosed with the ...Read more

Graduate student workers at Penn reach a tentative agreement, avoiding a strike

Penn’s graduate student workers have reached a tentative agreement on a first union contract, averting a strike.

The two-year tentative agreement includes increases to wages among other benefits.

“I am so proud of what we were able to accomplish with this contract,” Clara Abbott, a Ph.D. candidate in literary studies and member of the ...Read more

Despite warning signs, Pennsylvania failed to take action in massive fraud case

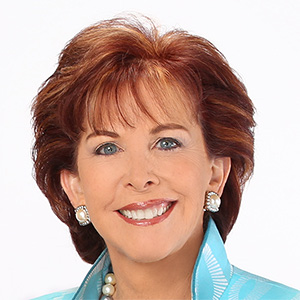

After weeks of investigating the inner workings of a giant investment company with ties to Pittsburgh, Toni Caiazzo Neff said she tried to do the right thing.

The former securities regulator had pored over the New York company's profit claims and mounting expenses.

She studied its purchases, including the acquisitions of car dealerships like ...Read more

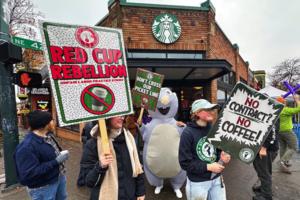

Starbucks CEO makes 1,794 times his average employee. Here's why

When Michelle Eisen and her fellow baristas organized an upstart union at a Starbucks, she and others were frustrated by the messaging from the top.

It was late 2021 and Starbucks’ then-CEO Kevin Johnson was making the rounds in the media to discuss Starbucks’ stellar year amid the pandemic. The company reported that it ended its fiscal ...Read more

Palantir is latest tech firm to move headquarters to Miami

Palantir Technologies Inc. said it’s moved its headquarters to Miami from Denver at a time when more tech firms are flocking to South Florida where local officials are promoting the region as an alternative to Silicon Valley.

The relocation announcement was made Tuesday in a brief statement on the social media platform X. A spokesperson for ...Read more

Investors snub the software dip, brace for deeper AI disruption

Investors are avoiding beaten-down software stocks, warning that the brutal selloff triggered by fears of displacement by artificial intelligence is likely only just beginning.

What’s quickly become known as the AI scare trade has ravaged major software names in the U.S. and Europe in recent weeks. Fund managers at the likes of Amundi SA and...Read more

Popular Stories

- Mayo Clinic testing Israeli magnetic-heating technology as cancer treatment

- How Ford's 'skunkworks' team is designing a more efficient EV

- Parents who blame Snapchat for their children's deaths protest outside company's headquarters

- Unprecedented 'jobless boom' tests limits of US economic expansion

- Google Gemini, Apple add music-focused generative AI features