Wells Fargo executives plot life after $36 billion punishment

Published in Business News

The buzz is building inside Wells Fargo & Co.: The bank — once the envy of the industry — could finally be allowed to grow again.

Seven years into a U.S. cap on assets, executives are awaiting a verdict on whether they’ve done enough to appease the Federal Reserve to get the restriction lifted. By one measure, it has cost the lender more than $36 billion in profits, easily making it one of the harshest corporate sanctions in a generation.

Now, up and down the ranks, managers are talking about what would follow. Chief Executive Officer Charlie Scharf has longed to ramp up trading operations. The firm could amass more deposits from corporations, and then lend more money to others. Initiatives, including a credit card in development to challenge JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s popular Sapphire Reserve, would have more room on the balance sheet to grow.

But more than anything, the talk among staffers keeps turning toward something less tangible: removing the black mark that dents morale and makes client interactions harder.

Such is the vibe inside the fourth-largest U.S. lender weeks into President Donald Trump’s second term, with authorities widely expected to ease regulation to stoke the economy. Though the Fed is independent, Michael Barr has announced plans to step aside as vice chair of supervision to avoid a clash with the new administration, allowing Trump to nominate someone else for the post.

On Sunday, the asset cap turned seven years old. Its unexpectedly long shadow has made it the industry’s most feared punishment.

“I didn’t disagree with it — I thought it was appropriate given how serious the problems were,” said former Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Chair Sheila Bair, who was a Republican appointee. “But I am surprised that it has been in place for so long.”

When it comes to lifting it, she said, “hopefully it’s not a political decision.”

When the Fed imposed the consent order, the sanction was so arcane and unprecedented that more analysts raised their ratings than lowered them in the months that followed. Executives wrongly predicted they could finish the work required for lifting it within a year or so.

It has proved incredibly tenacious and costly. The bank not only spent heavily to make fixes, it missed out on years of additional revenue it would have reaped had its balance sheet grown in line with major peers, especially once inflation hit. Based on the bank’s profit margins, those missed profits amount to roughly $36 billion.

Now, investors are optimistic the era may be nearing an end. The stock is up 47%, outperforming its main competitors, since Bloomberg reported in late September that Wells Fargo had taken one of the last major steps — submitting a third-party review of its risk and control overhauls to the Fed — as it tries to get the cap lifted.

But predicting the end has previously proved folly. Analysts who suggested years ago that it was almost over have rued their words. Some executives shepherding the process left or retired first.

And inside the Fed, multiple steps remain before the cap could come off — including a vote by its board.

This look at the asset cap is based on interviews with more than a dozen people close to the firm and the central bank at key moments in the sanction’s history. They asked not to be identified discussing the confidential process.

Spokespeople for the bank and Fed declined to comment.

Closet Discovery

How Wells Fargo ended up in the morass is a tale of hubris.

It starts with the bank underestimating public anger over the revelation in 2016 that it had opened millions of accounts without customer permission. As additional scandals surfaced, the Fed made the firm promise to overhaul risk management and oversight before it could grow further. But even then, executives failed to anticipate how many more problems they would find and what it would take to fix them all.

One example begins in the closet of a Wells Fargo branch years ago. A manager investigating a customer complaint about an out-of-date account balance peeked into the compartment to discover a mound of unopened deposit bags.

It turned out that Wells Fargo didn’t have an adequate system to make sure funds dropped off by customers were processed quickly. At a company with well over 200,000 employees across 4,000 locations, a gap in procedures invites human error, poor judgment or even laziness.

The bank had thousands of processes that it had to check for holes.

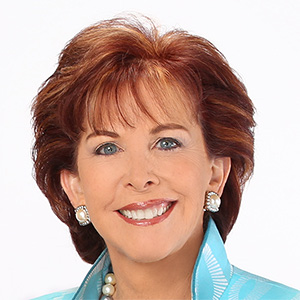

Scharf, 59, arrived as CEO about two years into the debacle. By then, the materials the firm had prepared on its shortcomings and fixes were becoming a tome — “like War and Peace,” one person familiar with the documents said. On his first day, Scharf fired off a companywide memo urging employees to clean up faster. He and his deputies were repeatedly shocked by how bad things were.

Under Scharf, the firm hired thousands of employees to bolster oversight of risks and controls. They spent years mapping processes and identifying things to shore up.

Each one meant a months-long ordeal. An executive assigned to a task would eventually face a panel that would grill them and score their work on a scale of 1 to 100. If the executive scored too low, they had to redo some work.

The novelty of the Fed’s punishment created other headaches. The bank and the regulator didn’t always see eye-to-eye on how to interpret the agreement they had signed. It took months, for example, to define exactly what it meant to “adopt and implement” remedies.

The cap chafed when the pandemic hit. With the U.S. government and Fed funneling trillions into the economy, many banks’ balance sheets swelled. But at Wells Fargo, executives conducted daily virtual “war rooms” to make sure the firm stayed in bounds.

The challenge spilled into public view when the first Trump administration unleashed hundreds of billions of dollars in emergency lending for small businesses. Banks served as intermediaries. But Wells Fargo figured it could arrange only $10 billion of loans before hitting its ceiling.

The firm put out a statement on the problem, annoying some inside the central bank. Both sides soon agreed to “temporarily and narrowly modify the growth restriction” so Wells Fargo could make more of the loans. When the initial $349 billion allocated to the program ran out days later, the lender had only arranged about $120 million. Small-business clients fumed.

Lightning Rod

When the cap began, Fed insiders didn’t expect the restriction to last so long. They were more focused on getting growth-obsessed Wells Fargo’s undivided attention.

The sanction echoed an earlier approach that proved effective. In 2016, the regulator asked too-big-to-fail banks to submit “living wills,” outlining how authorities could wind down their operations in an emergency. After Wells Fargo failed the review twice in one year, the Fed banned it from making certain acquisitions or setting up international units. The firm submitted a new version of its living will within months and won approval.

As senior Fed officials readied the broader asset cap, some of Wells Fargo’s top brass flew to Washington to argue against it. But that proved futile, and on Janet Yellen’s last day as Fed chair, the order was made public.

The sanction has since become a lightning rod. Prominent bank critics, such as U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, have advocated for asset caps while complaining that banks treat mere fines as a cost of doing business. The Democrat extracted a public promise from Yellen’s successor, Jerome Powell, that the Fed’s full board would vote before lifting the cap.

Last month, Scharf struck an optimistic tone on a conference call with analysts. “Our operational risk and compliance infrastructure is greatly changed from when I arrived,” he said. “While we are not done, I’m confident that we will successfully complete the work required in our consent orders.”

To other banks and their shareholders, a potential asset cap is now seen as a nightmare.

That was underscored in October, when an analyst asked Citigroup Inc. CEO Jane Fraser whether her firm is under a secret asset cap. First, she gave a vague answer, and later followed up: “Let me be crystal clear: We do not have an asset cap,” Fraser said. “And we’re not expecting any.” But by the time she clarified her answer, Citi’s shares had tumbled 5%.

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments